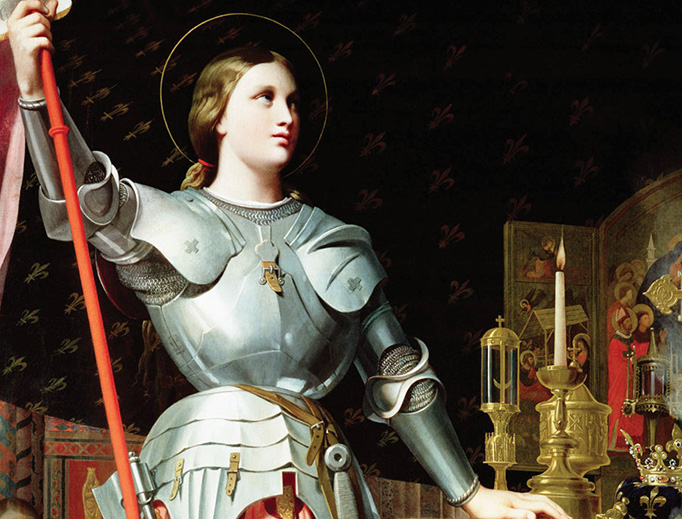

St. Joan of Arc on Stage, in Film and in the Catechism

St. Joan of Arc was canonized in 1920 not because of her military triumphs or her mystical visions, but because she loved Jesus and his Church.

On May 30, 1431, after being found guilty of being a relapsed heretic and witch, Joan of Arc was burned alive at the stake in Rouen, France. She died repeating the name of Jesus. Her family worked for years to have her rehabilitated; in 1456, she was cleared of all charges in another trial. Pope Pius X beatified her in 1909 and Benedict XV canonized her in 1920. As patron saint of France and of soldiers, statues of her are often featured in French cathedrals and churches with the memorials to the thousands of dead in World War I and her image was also used in recruiting posters during that War to End All Wars.

St. Joan of Arc is a popular saint among dramatists and novelists: George Bernard Shaw wrote a play about her, as did Jean Anouilh, Charles Peguy and Maxwell Anderson. St. Thérèse of Lisieux was very devoted to St. Joan and portrayed her in convent plays in 1894 and 1895. Shakespeare included her in one of his history plays, Henry VI, Part 1; because she fought against the English in France, Shakespeare is not sympathetic to her at all. Voltaire and Friedrich Schiller wrote plays about her in French and German with drastically different views.

St. Joan has been portrayed in movies by actresses ranging from Renée Jeanne Falconetti (The Passion of Joan of Arc), Ingrid Bergman, Jean Seberg, Milla Jovovich, and Leelee Sobieski. The actress known as Valli (the Baroness Alida Maria Laura Altenburger von Marckenstein-Frauenberg) portrayed St. Joan of Arc in the movie within the movie, The Miracle of the Bells.

Tchaikovsky wrote an opera about her based on Schiller’s play; Arthur Honegger wrote an oratorio using the poetry of Paul Claudel as a libretto.

Samuel L. Clemens loved her. He said of her:

She was a beautiful and simple and lovable character. In the records of the Trials this comes out in clear and shining detail. She was gentle and winning and affectionate, she loved her home and friends and her village life; she was miserable in the presence of pain and suffering; she was full of compassion: on the field of her most splendid victory she forgot her triumphs to hold in her lap the head of a dying enemy and comfort his passing spirit with pitying words; in an age when it was common to slaughter prisoners she stood dauntless between hers and harm, and saved them alive; she was forgiving, generous, unselfish, magnanimous; she was pure from all spot or stain of baseness. There is no blemish in that rounded and beautiful character.

Under his pen name, Mark Twain, he wrote a great historical novel, purporting to be a contemporary chronicle. He loved her so much that he even acknowledged her Catholic faith without reserve — and Clemens/Twain had no respect for organized religion.

St. Joan has been cast as a madwoman, a feminist, a visionary, a martyr, a patriot, a warrior — but as Pope Benedict XVI noted in his General Audience of Jan. 26, 2011, she is a saint worthy of being cited in the Catechism of the Catholic Church several times.

Statements from the 1431 Trial

Although she was a simple peasant girl, St. Joan’s replies to some of the questions posed to her during her trial for heresy were clear and concise enough to confound her judges. They documented her answers, so these are not legendary; these are part of an official court record.

In the Catechism’s discussion about “The Church: The Body of Christ” (795), St. Joan is cited in one of the supplemental comments:

A reply of St. Joan of Arc to her judges sums up the faith of the holy doctors and the good sense of the believer: ‘About Jesus Christ and the Church, I simply know they're just one thing, and we shouldn't complicate the matter.’

She is also cited in the section discussing “Grace and Justification” (2005) in the context of how we can know if we are in the state of grace:

A pleasing illustration of this attitude is found in the reply of St. Joan of Arc to a question posed as a trap by her ecclesiastical judges: Asked if she knew that she was in God's grace, she replied: ‘If I am not, may it please God to put me in it; if I am, may it please God to keep me there.’

Two of her sayings are also cited: in the section on “The Implications of Faith in One God,” she is quoted in paragraph 223: “Therefore, we must serve God first.” Finally her last words are referenced in paragraph 435: “Many Christians, such as St. Joan of Arc, have died with the one word, Jesus, on their lips.”

When Pope Benedict celebrated her in his series of talks on Holy Men and Women of the Middle Ages and Beyond, he offered some insights into how St. Joan was able to answer great theologians so perceptively:

Dear brothers and sisters, the Name of Jesus, invoked by our Saint until the very last moments of her earthly life was like the continuous breathing of her soul, like the beating of her heart, the centre of her whole life. The Mystery of the Charity of Joan of Arc which so fascinated the poet Charles Péguy was this total love for Jesus and for her neighbour in Jesus and for Jesus. This Saint had understood that Love embraces the whole of the reality of God and of the human being, of Heaven and of earth, of the Church and of the world. Jesus always had pride of place in her life . . . Loving him means always doing his will. She declared with total surrender and trust: “I entrust myself to God my Creator, I love him with my whole my heart” (PCon, I, p. 337). With the vow of virginity, Joan consecrated her whole being exclusively to the one Love of Jesus: “it was the promise that she made to Our Lord to preserve the virginity of her body and her mind well” (PCon, I, pp. 149-150).

And he concluded: “Dear brothers and sisters, with her luminous witness St Joan of Arc invites us to a high standard of Christian living: to make prayer the guiding motive of our days; to have full trust in doing God’s will, whatever it may be; to live charity without favoritism, without limits and drawing, like her, from the Love of Jesus a profound love for the Church.”

The Total Love for Jesus

St. Joan may be known as the great warrior saint of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France — which actually lasted 116 years between 1337 and 1453 — who liberated Orléans and brought King Charles VII to the throne. She is famous for her visions and mourned for her cruel death at the hands of judges, who as Pope Benedict said, “were theologians who lacked charity and the humility to see God’s action in this young woman” and “were radically incapable of understanding her or of perceiving the beauty of her soul.” As he reminded us in 2011, however, St. Joan of Arc was canonized in 1920 not because of her military triumphs or her mystical visions, but because she loved Jesus and his Church, even when she was condemned by an ecclesiastical court.

This article originally appeared May 30, 2017, at the Register.

- Keywords:

- st. joan of arc