Archaeologist Uncovers Thousands of Rare Items in Catholic Tudor Manor

Discoveries made during repairs to house in England include fragments of medieval books and handwritten music likely to have been hidden by devout family.

In August 2020 it was announced that an archaeologist working alone through lockdown in the attic rooms of an English moated manor house, Oxburgh Hall, had uncovered one of the largest underfloor archaeological discoveries of its type.

Oxburgh Hall is situated in Norfolk, England, and was built by Sir Edmund Bedingfeld after he inherited the estate in 1476. It remains the Bedingfeld family home today. Oxburgh and the family, who have remained Catholic down the centuries, have endured turbulent times: religious persecution, the devastation of the English Civil War, near destruction and threatened demolition.

Oxburgh’s history has been one of survival. Through it all, the Bedingfeld family remained steadfast in its heart, suffering persecution for their Catholic faith.

The variety and age of the recently found items and what they reveal about the history of Oxburgh Hall make this a unique discovery.

“The finds at Oxburgh are a window into the world of a gentry family,” explained Anna Forrest, the National Trust curator who is overseeing the restoration work. “The discoveries allow us to build up a picture of what they [the family] wore, what they read, the pastimes with which they and their servants were occupied (e.g., sewing, reading, music-making, shooting, writing), what uses the rooms at Oxburgh were put to in the past, and what high-status belongings the family owned.”

Floored to Discover

From the many items dating back to the Tudor period, there is, notably, a page from a rare 15th-century illuminated manuscript. “We believe the manuscript page is from a Book of Hours,” said Forrest. “Books of Hours were portable prayer books for private devotion typically comprising a series of prayer cycles known as Hours or Offices: the most common being those dedicated to veneration of the Virgin Mary or remembrance of the dead. Their use represented a more personal approach to religion, different from the communal clergy-led devotion of the parish church, and they were massively popular. So whomever this book belonged to was participating in this more private form of worship.” She added, “The single page found at Oxburgh therefore represents the family’s approach to devotional practice in the years before the Reformation and their wealth and prestige.”

Other finds include fragments of late 16th-century books and high-status Elizabethan textiles, as well as more mundane modern objects such as cigarette packets and an empty chocolate box that date back to the Second World War.

The surprise discovery was made during the repair of the roof of Oxburgh Hall. This work included lifting many of the floorboards in the attic rooms to repair floor joists. Earlier this year, despite England’s COVID-19 lockdown, independent archaeologist Matt Champion agreed to continue to work on alone at Oxburgh Hall. He told the Register, “It was certainly a strange time. I began at Oxburgh shortly after lockdown in the U.K. — driving to the site each day along empty roads and beneath empty skies. There were also very few of us actually on site: a skeleton staff from the National Trust and a handful of building specialists. It's a big house, and it was easy to pass the day without really seeing anyone else, particularly when you are spending that time with your head beneath the floorboards. It made it a very personal and intimate experience.”

It was while carrying out a careful finger-tip search that the unexpected discovery was made. “Making any discovery is exciting,” Champion said. “A lot of archaeology is a very slow, methodical process. So when something appears that is clearly significant, you can’t help but feel that moment of slight elation, knowing that you are the first person to set eyes upon this object for centuries: wondering who was the last person to touch it. In buildings’ archaeology, such discoveries are rare, so Oxburgh was very different.” Champion added, “Nobody knew what fresh excitement each day might bring.”

Raised From the Dust

Forrest explains that it was the first time anybody had searched under the Oxburgh Hall floorboards in centuries: “When the boards came up, we could see a wave pattern in the debris, which showed it had been undisturbed for centuries. The peak of each wave of dust, debris and objects was highest under the crack between the boards. It was often inches thick and lay on top of a layer of lime plaster, which drew out the moisture from the debris and resulted in much of it being perfectly preserved over the centuries.”

Forrest continued, “One particular challenge was in areas with south-facing windows, where hundreds of pins were found, so Matt [Champion] had to use thick gloves when searching. The rooms, being well lit, had clearly been used for sewing and for organizing correspondence, with evidence of wax seals and fragments of late 18th-century handwritten documents in English and French.” Summing up the find, she added that “the value of underfloor archaeology to our understanding of Oxburgh’s social history is enormous.”

Although the house is currently owned and run by the National Trust, the Bedingfeld family continue to live in part of the building today. The present head of the Bedingfeld family, Sir Henry Bedingfeld, is resident at Oxburgh Hall. The Register asked him how he felt upon hearing of the recent find. “I was intrigued, delighted. It was totally unexpected. The National Trust has never seen such a find,” he replied.

Bedingfeld hopes that once further funds become available for future exploration that “there will be more [finds] to come, as only some of the floor boards have been lifted.”

He views some of the items found as being valuable links with the sufferings of his Catholic ancestors. How many of the objects discovered belong to the family’s Recusant Catholic past? “That’s very difficult to say,” said Forrest. “We know that the family refused to sign Elizabeth I’s Act of Uniformity, which outlawed the Mass, and from that point onwards, they were ‘recusants,’ whose refusal to attend the services of the Church of England was a statutory offense. We know that Sir Henry Bedingfeld was summoned to court in 1578 to answer charges of ‘disobedience in matters of religion’ (although he didn’t attend, owing to ill health) and that in the late 16th century the ‘priest hole’ was constructed at Oxburgh to shelter Catholic priests from discovery.”

Forrest also pointed out that in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum there is a pre-Reformation chalice and paten from Oxburgh Hall, “the rare survival of which surely reflects their continued use and careful concealment.” Forrest speculated that “the family may have commissioned a makeshift chapel in the attics, which were constructed in the second half of the 16th century after that area of the house was re-roofed.” She also sees one of the books discovered as having a tangential link to the house’s Catholic past. “Amadis de Gaulle, from which we found some tiny fragments, was an Iberian chivalric romance which was particularly popular with Catholic readers, owing to its Spanish origins and references to Catholic practices in the text.”

Results Through the Roof

Russell Clement, general manager at Oxburgh Hall, commented: “We had hoped to learn more of the history of the house during the re-roofing work and have commissioned paint analysis, wallpaper research, and building and historic graffiti recording. But these finds [in the roof] are far beyond anything we expected to see. These objects contain so many clues that confirm the history of the house as the retreat of a devout Catholic family who retained their faith across the centuries.”

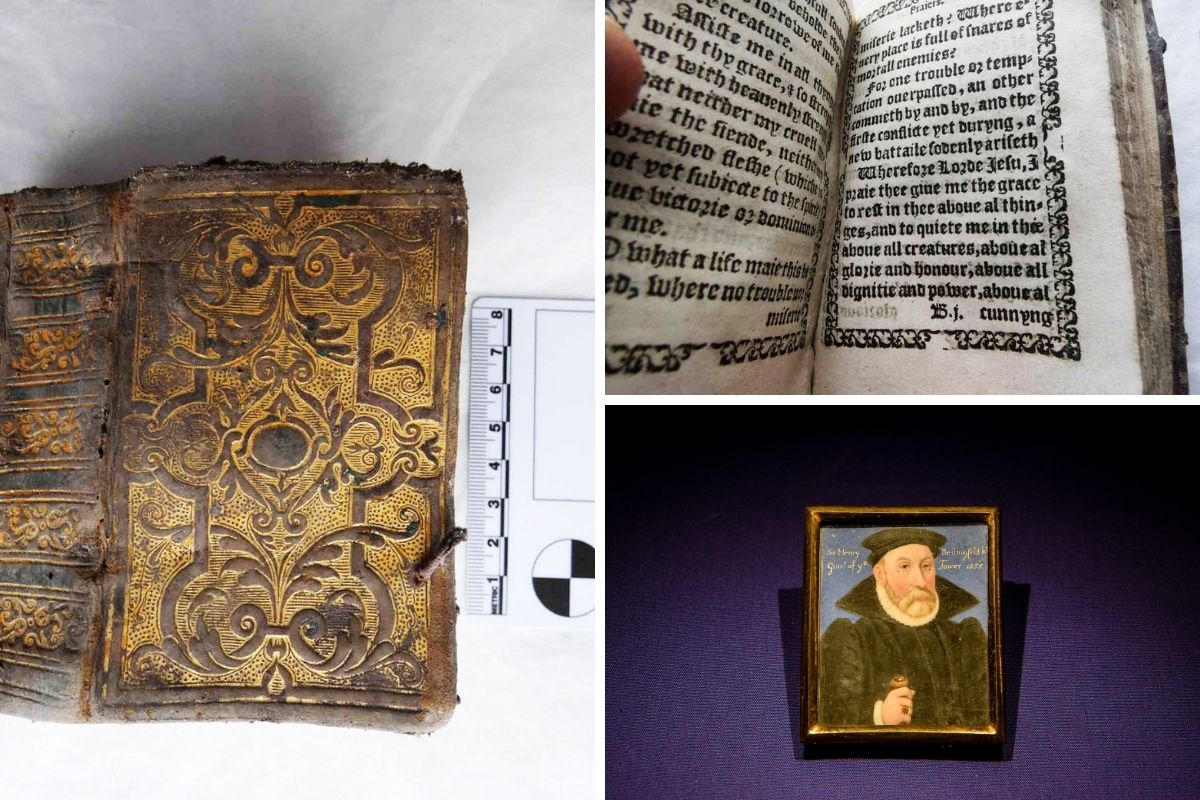

The discoveries have continued to be made as a result of the building work. One builder spotted in an attic void a complete book called the King’s Psalms, dating from 1568. Complete with its gilded leather binding, the book is almost intact. Further research into the book continues.

“This is a building which is giving up its secrets slowly,” Clement added. “We don’t know what else we might come across — or what might remain hidden for future generations to reveal.”