In Memoriam: George Weigel Pens Elegies for Myriad of Lives

BOOK PICK: Many of the lives highlighted in ‘Not Forgotten’ were friends of the great Catholic author and essayist, and many were those he simply had a deep admiration for.

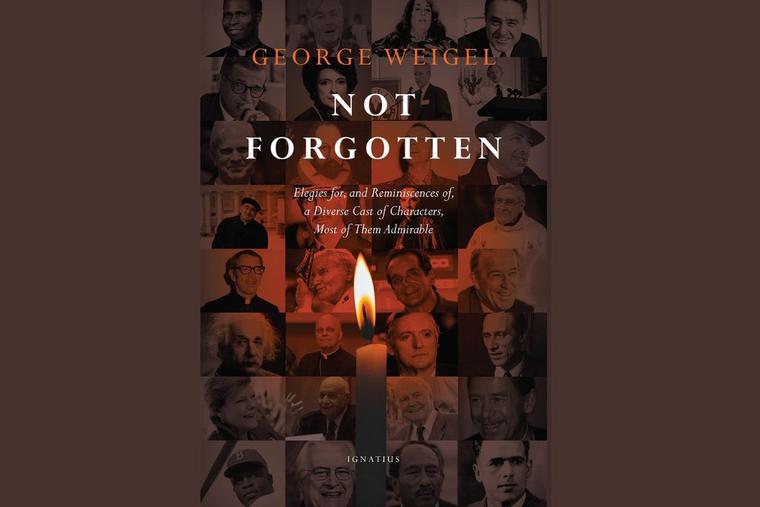

NOT FORGOTTEN

Elegies for, and Reminiscences of, a Diverse Cast of Characters, Most of Them Admirable

By George Weigel

Ignatius Press, 2021

215 pages, $17.95

To order: ewtnrc.com or (800) 854-6316

At the conclusion of the first essay in George Weigel’s wonderful new book of profiles — profiles of the well known and the lesser known — he writes the following of a man likely in the latter category of popular recognition:

Faoud Ajami, a “critical Arabist, who died in 2014, despaired what was happening among his own people.”

“He mourned the catastrophic condition of contemporary Arab civilization,” Weigel explains, “who deplored the hijacking of Arab politics by self-serving dictators, virulent anti-Semites and Islamic fanatics.”

Weigel concludes this first of his 61 mini bios with this:

“May the great soul of this man of reason and decency be an everlasting memory and inspiration to others.”

Those final words could apply to nearly all of the people he profiles in his latest book, Not Forgotten: Elegies for, and Reminiscences of, a Diverse Cast of Characters, Most of Them Admirable.

Many of the lives highlighted in Not Forgotten were friends of the great Catholic author and essayist, and many were those he simply had a deep admiration for.

Weigel’s ability to say a lot over a mere two or three pages per subject proves that brevity can be a journalistic virtue.

Some of the names will be immediately familiar: baseball star Jackie Robinson, Catholic novelist and essayist Flannery O’Connor, the great conservative William Buckley, baseball manager Earl Weaver and Pope St. John Paul II — and many others who contributed to our culture.

He pays homage to several of those Christians who were martyred for refusing to bow down to the crooked cross of Nazism. Profiles of Catholic Blessed Franz Jägerstätter and the Lutheran Sophie Scholl should be required reading for those who admire sticking to one’s conscience. Delving deeper into their lives should almost be a duty of a decent person.

In the introduction, Weigel writes that most of those he profiled “wrestled with profound changes that have come to the Church and the world” in his lifetime. And many of those he admired have recently passed away.

Their collective legacy, what binds most all of them together, he writes, is each has something to teach us today about “righteous and noble living.”

But some of the 61 “teach those lessons along the old via negativa” and are not necessarily to be emulated.

Take folk singer Pete Seeger, who died in 2014. Weigel mischievously rewrites the title of Seeger’s famous If I Had a Hammer to If I Had a Hammer and a Sickle, noting the champion of the folk-music revival in America had an unfortunate admiration for the champion of totalitarianism, Stalin.

When Seeger left this vale of tears he went to meet his political maker, Karl Marx, writes Weigel, not missing another opportunity to get in another jab.

His profile of Einstein shows what an inventive writer Weigel can be, joining together the great German scientist with the Blessed Virgin Mary under the heading “A Meaningful Cosmos.”

Readers learn that in Weigel’s study once hung two pictures: a famous photo of Einstein alongside a Russian icon of the Mother of God.

Weigel was drawn to the eyes of these two iconic figures:

“When you look into the sad, wise eyes of the Vladimir Mother of God or of [photographer] Haslman’s Einstein, you learn duty, obligation, loyalty, and painstaking work are as revelatory of the meaning of human life as pleasure, ecstasy, or ‘doing your own thing.’”

Not all of the profiles are about those who were contemporaries.

In “The Well-Dressed Astronomer,” Weigel observes that Tycho Brahe, who passed in 1601, never went into his observatory unless he was dressed in the best of his finery.

The Danish astronomer developed astronomical instruments and took measurements of the stars that opened the door to future discoveries.

Weigel, though, makes the point that Brahe’s dressing up to do his work was not mere vanity, but a way to show deep respect to God’s cosmos. For Brahe, wearing his finery was a true “act of faith.”

Regarding Flannery O’Connor, “The Hillbilly Thomist as Apologist,” Weigel does some of his best work.

Few Catholic novelists and essayists were as groundbreaking as O’Connor, who died in 1964 at the far-too-young age of 39. She was best known for the novel Wise Blood, her book of short stories, and several collections of brilliant essays — still relevant nearly 70 years on.

“Flannery O’Connor was an exceptionally gifted apologist, an explicator of Catholic faith who combined remarkable insight into the mysteries of the Creed with deep and unsentimental piety, unblinking realism about the Church in its human aspect, puckish humor — and a mordant appreciation of the soul-withering acids of modern secularism,” writes Weigel.

He suggests that O’Connor could be a candidate for sainthood, for she was an “exemplar of heroic virtue, worthy to be commended to the whole Church.” (Though not all would agree with this assessment.)

There are many problems in our modern culture. Many of us are enthralled with celebrity. That may sound like harmless fun, but it is not. Idolizing those with far more glitz than substance sends a message that fad rules over the timeless — that immediate feelings are more important than an honorable path.

But the way to righteousness is the hard path, as Weigel delineates throughout Not Forgotten.

Charles Lewis writes from Toronto.

- Keywords:

- book picks

- george weigel