Speculation, Monopoly, Subprime Mortgages — and the Common Good

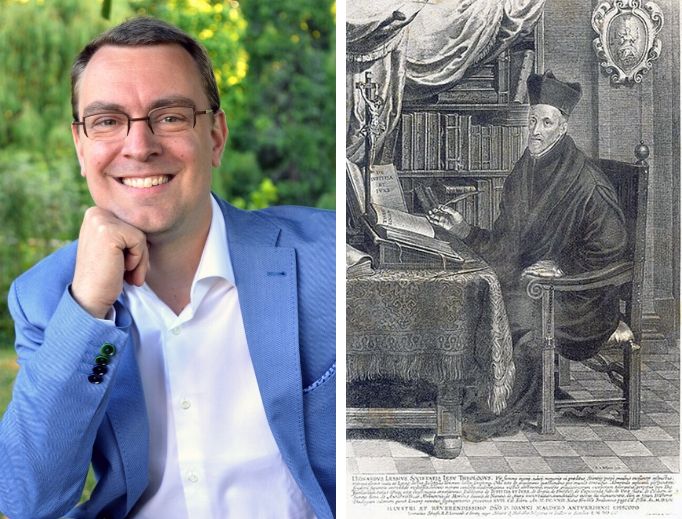

Belgian Catholic scholar Wim Decock discusses the intellectual legacy of Leonardus Lessius and why this great Jesuit thinker’s economic ideas remain relevant today.

The Catholic contribution to our modern legal and economic system is often underestimated — but one Jesuit scholar working in the 16th and 17th century, Flemish Jesuit Leonardus Lessius (1554-1623), may provide a key to sound Catholic economic principles for today’s capitalist markets.

The complex and ambivalent relationship that over the centuries Christendom has had with theories concerning the creation and accumulation of wealth stems from the fact that, while based on doctrine, the issues themselves are essentially prudential.

The complexity involved in Catholic views on financial and economic theories is compounded by the persistent belief that capitalism is theologically and philosophically rooted in Protestantism — a view that has generated a certain reluctance in the Catholic intellectual world to study market mechanisms.

But in the centuries before the Protestant Reformation in Europe, numerous Catholic moral theologians laid the foundations for the modern capitalist spirit, including Lessius, whose erudition and wisdom in economic theory earned him the nickname of “the Netherlands’ Oracle.” Lessius is considered an important figure in the Catholic theological and philosophical system known as Scholasticism, which was active between the 12th and 17th centuries. The Flemish Jesuit was also a prominent member of the School of Salamanca, a group of Scholastic scholars in Spain who sought to reconcile the thought of Thomas Aquinas with the political and economic realities of the late medieval and early Renaissance world.

Lessius’s teachings, forgotten over time because of the lack of translation from Latin to other languages, have been brought up to date in the book Le marché du mérite: Penser le droit et l’économie avec Léonard Lessius (The Market of Merit: Thinking Law and Economics With Leonardus Lessius) by Belgian scholar Wim Decock.

Decock is a professor of legal history at the University of Leuven and at the University of Liège (Belgium). He is the author of numerous books and publications in several languages, among which Theologians and Contract Law: The Moral Transformation of the Ius Commune (ca. 1500-1650) (2012) won the Raymond Derine Prize 2012 and the ASL-Prize in Humanities and Social Sciences 2012. It was also singled out as “law book of the year” by the German legal magazine Neue Juristische Wochenschrift.

The Register spoke with Decock about contemporary challenges to the capitalist system in the light of Lessius’ intuitions, as well as of some of his fellow late-Scholastic theologians.

Leonardus Lessius’ thought has been very influential over the centuries and has even inspired the greatest economists of modern times, such as Adam Smith or Joseph Schumpeter. How do you explain the fact that he is so little-known within the Catholic world nowadays?

First of all, I would say that almost all of the sources about his work are in Latin and haven’t been translated. Given the fact that less and less people are able to read Latin, important authors like Lessius or others from the School of Salamanca are losing momentum. The only authors we remember in the legal or philosophical community are Francisco Suárez or Robert Bellarmine, and it could be explained by the fact that many translations exist and are in circulation in Italian, Spanish, English or French. Lessius, just like many other authors I quoted in my book, were never translated, so we lost access to their work.

And I also believe there was a kind of anti-legal turning point within the Church in the 20th century, whereas I believe that Lessius and the School of Salamanca are rather an expression of a Catholic culture that used to be strongly inspired by Roman law and canon law. From the 20th century, the Church started being more attracted to other forms of knowledge, like psychology, and tried to express the Gospel message using another terminology. Such a tendency was further rooted after Vatican II.

As a historian specializing in the 16th century, I sometimes have the impression that the Catholic Church somehow “Protestantized” itself on these specific issues.

But that progressive rediscovery of this part of our heritage creates opportunities. I notice that my work is attracting more and more people within various intellectual circles that know very little about the Church but are curious to know more about the roots of our modern political and economic system. From inside the Church, it reinvigorates debates and curiosity about our forgotten great thinkers.

You’ve just mentioned Protestantism. You dedicate a whole chapter to Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, refuting the thesis that modern capitalism is rooted in Protestant theology. But why are modern Catholic scholars so hesitant to contradict Weber’s theory?

During the 20th century, a few authors did venture to fight Max Weber’s theories from a Catholic point of view, drawing from medieval tradition, and wanted to affirm the presence of a capitalist spirit within the Jesuit order, for instance. It was the case of Hector Menteith Robertson with Aspects of the Rise of Economic Individualism (1933). But then he was kind of “excommunicated” by some Catholic colleagues who really didn’t want to be associated with capitalism. Indeed, many of them were happy that something they considered negative was associated with a Protestant heritage rather than with Catholics.

Actually, there was a kind of shift in the Catholic intellectual world after the publication of Weber’s Ethic with regard to capitalism. Then the 1929 [economic] crisis [precipitating the Great Depression], followed by Pius XI’s encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, consolidated such tendency.

But before the Industrial Revolution, in the 16th and 17th centuries, capitalism and solidarity were not opposed. The 1930s were a very specific period of time, so we must be careful not to project some anachronic images on the past.

And I would also add that there is the tendency to oversimplify Weber’s theory, as he actually sees the roots of the capitalist spirit in the Christian “spirit of ascesis [self-discipline],” which was very present in the medieval world, as well as in the “Puritan” Protestantism of the 17th century. And it is well-known indeed that Martin Luther was totally hostile to capitalism.

If the “spirit of ascesis” is an essential element of modern capitalism, does this mean that our postmodern materialistic capitalist societies are structurally condemned to failure, as Pope Benedict XVI suggested on several occasions?

At the beginning of the 20th century, Max Weber already highlighted the fact the capitalist system could grow thanks to the ascetic spirit’s thirst for accumulation of capital, which implied that we couldn’t enjoy our wealth and that it was just the accomplishment of a duty. And Weber already pointed out that capitalism had been entirely uprooted with respect to its original spirit, as most capitalists were no longer inspired by such an ascetic spirit.

The virtues of temperance and prudent are also central in Lessius’ work, who often speaks about the risk of self-destruction in the absence of this spirit of self-denial. Lessius and his fellow medieval theologians from the School of Salamanca don’t advocate immoderation; on the contrary. They could be seen as the forerunners of ordoliberalism [which sees involvement of the state as essential to a successful market economy]: They want to stimulate individuals’ freedom, their prudence, their work, but this must happen within a certain framework that must respect order and protect society against self-destruction.

So you are right in seeing a clear warning in their promotion of a “spirit of ascesis”: If capitalism switches to a thirst for money, the whole system become corrupted and is no longer sustainable.

The notion of usury (which originally meant the charging of interest of any kind for a loan) is a pretty delicate issue and an important topic of Lessius’ work. What are his insights into the traditional proscription against usury?

Lessius takes very seriously the concern of those who condemn usury; that is, exploitation of the weakest parts of the market. He reckons that a businessman must show solidarity and charity toward the participants in the market that are in need, that don’t have enough knowledge of the world, and so on.

On the other hand, there is a very important change with respect to tradition in the work of Lessius and of other Jesuits of his time. We notice a more lenient understanding toward what happens in practice. In Lessius’ case, such understanding was based on the Bourse of Antwerp [the first world financial exchange], which he observed in an empirical manner. He saw prudent and experienced Christian businessmen evaluate the price of money. After seeing them doing this widespread practice, he eventually accepted it; it appeared to him that tradition was no longer in line with empiric reality. There is a very optimistic anthropology behind his approach: If such custom is so widely spread, even among decent businessmen, it means that it cannot be totally evil.

This is a major difference between the Jesuits of this time and the Puritans. The latter will say that God’s commandments go against people’s customs because human beings are evil because of the original sin. So the law is made to go against our intuitions and spontaneous practices within the market.

On the contrary, Lessius, on the basis of his optimistic anthropology, which is also related to his conception of free will and grace, acknowledges the fact that money is a good like any other, which can be evaluated at a certain price that reflects some factors in the market, like supply and demand. This is how he offered a whole economic analysis on the mechanism of prices within the financial markets. It was something very innovative, and it definitely brought an important contribution to the development of economic sciences.

What does Lessius say about financial speculation?

Lessius weighs different values and virtues. His acceptance of speculative behaviors is founded on the acceptance of what he calls the “mercantile condition,” the condition of the businessmen, which consists in foreseeing the evolution of the market, which is related to prudence, to farsightedness. So he wants to remunerate the businessman who built a whole network of information between people, to get adequate updates of the evolution of the market. He wants to remunerate this businessman for his work, his intelligence and personal investment. Of course, in his opinion, the context is one of a professional market, and not an amoral universe, because it encourages the businessman to think not only about his own interests but also about the interest of others in a market, including poor customers.

What is Lessius’ moral and commonsense argument in favor of free competition?

I would say that the common denominator of the Scholastic school of the 15th and 16th centuries, which doesn’t concern only Lessius, is that free competition and the free market must be respected because in the Scholastics’ opinion it is the best guarantee for common interests, the best way to prevent exploitation from those in a dominant position.

There is no Latin equivalent for free competition in the Scholastic books, but we can find very long remonstrations against monopolies, a term which refers to dominant positions, cartels, monopolistic privileges granted by public authorities because the Scholastic authors assume they can damage the common interest, as they provoke abuses. So the Scholastic authors side against monopoly rather than supporting free competition principles, but in practice, their fight against monopolies amounts to defending free competition.

Do they mention specifically the kind of abuses monopolies can generate?

Regarding monopolistic privileges granted by public authorities, which were common place at that time (and it is still the case today), Lessius, Luis de Molina and other theologians said that it can be harmful for buyers and customers, as it allows the associates of companies to sell their products at a far more expensive price than if there was no monopoly. It was the case for the spice trade in India, for instance. Therefore, they advised princes not to grant these monopolies — on pain of sin — and if they did, to at least restrict it.

So they were distrustful of every form of abuse of power, which can come from businessmen but also from public authorities who interfere arbitrarily in the market. It is a common thread in their thinking.

How would Leonardus Lessius define the Christian spirituality of work?

I would say his teaching proposes a perfect balance between commitment and self-denial. On the one hand, it is necessary to apply oneself in order to put in practice the virtue of industria (industriousness); that is, constant diligence, which is accompanied with intelligence. It is not good to work too much without thinking about our lives, without taking the time to live. So the virtues of prudence and temperance are once again typical of Lessius’ spirituality, which is deeply Christian. Temperance makes human beings understand that their ultimate destiny is life with God after death and that work cannot be the only thing that matters.

The kind of morality Lessius advocates is illustrated in other books, especially when he speaks about food. He actually gives pieces of advice, like a dietician; it is quite amusing. He seeks to stimulate people’s freedom by saying there are too many books with precepts about how people should eat, which suffocate their freedom.

But on the other hand, he says that moderation is always appropriate and that we should avoid excesses. Speaking about great banquets, he wrote that when temptation is very strong, people should be careful and exercise the virtue of temperance by eating only one scoop of ice cream instead of three, for instance.

So we always find the same tension between liberality and rigor in his work. He respects carnal and earthly desires of human beings, but he will always encourage limitations, just like in professional life. We must keep in mind that common good is rooted in Lessius’ thought and heart. This is what distinguishes him from secular capitalist societies.

“We were born for public good,” Lessius once wrote. What is the best way to seek this good — that is, the common good — in his view?

His perspective goes against the intuitions of many people, and even people within the Church, even though they are full of good intentions. Lessius thinks that, in seeking the common good, we have an interest in implementing a credit system, for instance, which works very well and which implies a system of return on capital. Otherwise, those who have savings will never be willing to invest their capital in projects that will be interesting and profitable for everyone in the society.

So his notion of public utility, of common good, doesn’t only imply solidarity, which he expresses through the essential notion of caritas (charity). Beyond this necessary duty, the common good implies that we stimulate businessmen’s industry and investment mechanisms that enable capitalists to grow rich in a relatively safe way.

Lessius legitimated these legal tools for commercial capitalism precisely for utilitas publica (public utility) and bonum commune (common good). He believed it could favor prosperity for the whole community. And such a belief was actually confirmed by what he witnessed at the Bourse of Antwerp: Its success was accompanied with a great prosperity for public community in this city.

At this time, there was no contradiction between a businessman who was seeking his own interest and the interest of a community. Such an opposition is very modern.

Let’s talk about the contemporary question of “subprime,” to which you dedicate a whole chapter of your book. What would be Lessius’ analysis of the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis?

At Lessius’ time, the technique of reselling securitized financial products [which was a central element of the mortgage crisis] was far less widespread, because even some algorithms can do that nowadays. But we can see that Lessius hesitated to condemn purely and simply this practice at the beginning. You can see it from the way he builds his argument. He initially developed a series of arguments which legitimate this practice. He says that debts have a price in a market, just like any other product, and he sees there are debts we can buy; for instance, for 10% of their intrinsic value. The one who buys this kind of product, usually, can expect that such a low price reflects bad debts, so the price somehow indicates that the product is very problematic. Therefore, the one who wants to buy it must bear the risk. This is the kind of thinking he develops, referring also to the legitimacy of speculation.

But in the end, he changed his mind and condemned this practice. So I believe he would definitely condemn the massive industry surrounding the subprime mortgages nowadays. Indeed, he said that it is like selling a sterile field to someone, which is not the right thing to do. We cannot sell sterile agricultural land to farmers; it doesn’t make sense. He realized that endorsement for subprime mortgages was too forward, and he back-pedaled.

As an advocate of free trade, what would Lessius think about U.S. President Donald Trump’s protectionist policy? American conservatives themselves are pretty divided on this specific topic.

There are two different approaches within the Scholastic tradition on this issue. On the one hand, there is a big openness toward both national and international trade; and on the other hand, we can hear more skeptical voices. Leonardus Lessius is rather in favor of free international trade, whereas Tomás de Mercado is more skeptical. But in a more general way, the so-called late-Scholasticism of the 16th and 17th centuries develops the idea that divine Providence ensured that the different parts of the world don’t have everything they need for their own subsistence.

Therefore, they legitimated international trade by referring to divine Providence. Some theologians very explicitly praised these encounters between businessmen from different cultures and countries because they thought it contributed to their mutual understanding. And Lessius is a kind of prototype of this current of thought.

But Tomás de Mercado has another theory. While saying that we cannot do without international trade, he also stressed that public authorities should take care of this and name national businessmen to organize trade with other countries. Thus there would be a certain control over these businessmen who would become in some way government employees. He explains such theory by the fact that businessmen tend to be too easily fascinated by foreign moral customs and cultures and that it is a threat to our cultural identity.

In short, the theologians of the late Scholastic tradition tend to be mostly against protectionism, but that doesn’t prevent them from being careful about the cultural effects — and not the economic effects — of international trade.

Solène Tadié is the Register’s Rome-based Europe correspondent.

- Keywords:

- business ethics

- capitalism

- economics

- solène tadié