Museum of the Bible Exhibit Tells the Stories of Persecuted Middle East Christians

‘Cross in Fire’ gives tangible expression to the suffering of Christians, raising international awareness of their plight.

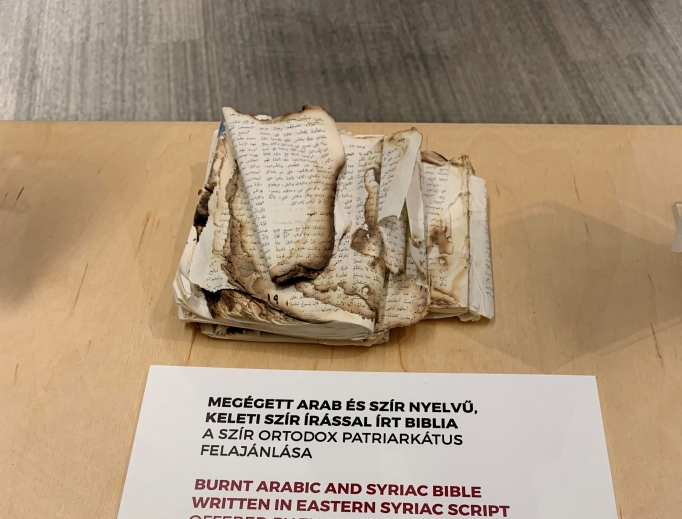

WASHINGTON — The haunting faces of Christian refugees surround desecrated religious books and statuary at the new “Cross in Fire” exhibit at Washington’s Museum of the Bible.

And the churches being destroyed, and the Christians being injured and killed, are not museum pieces dating from hundreds of years ago — they are images of what Christians face in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa today.

The exhibit, on loan from the Hungarian National Museum, was opened Feb. 5 following remarks from U.S. members of Congress and Hungarian officials about the importance of making the world aware of the persecution Christians are still facing in these regions.

The temporary exhibit, on display at the museum until March 2, documents the destruction of ancient Christian communities by terrorist groups with pieces of this destruction, including a badly damaged tabernacle door from the Armenian town of Kessab, Syria, which was under the control of the Islamist terrorist al-Nusra Front in 2014. A statue fragment of Mary’s veil with cracks and bullet holes from the Chapel of St. Addai in Batnaya, Iraq, sits under glass. The piece was donated by the Chaldean Catholic Church, after the destruction wrought by the Islamic State group (ISIS).

Alongside the badly damaged sacred imagery, the exhibit is lined with striking pictures of Christians trying to rebuild their lives after harrowing escapes. On one side of a panel, Rahila Goldwin, 34, stands scarred but smiling. The other side of the panel tells the story of how Fulani militants attacked her village in Kaduna State, Nigeria, killed her 6-year-old child and husband, brutally raped her, caused her to miscarry, as she was six months pregnant, and cut off her right hand. She now lives in a refugee camp with other victims of the violence.

Oumayma Hazem Aziz is featured on another panel with her two sons in a refugee camp in Erbil, Iraq. In 2004, her husband was murdered in front of her and her 2-year-old son by two Islamist gunmen in Mosul, Iraq. Her son Nawwar is still afraid to go out on the street by himself because of the attack. She and her sons lived in Qaraqosh, but had to flee ISIS on foot in 2014.

‘Martyrs of the Present’

Tristan Azbej, the Hungarian state secretary for persecuted Christians, gave remarks before the exhibit opened, reminding those gathered of the urgency of the issue.

“Eighteen years,” he began, “this is how young a Christian Nigerian seminarian was, who was kidnapped a few weeks ago. For weeks, we didn’t know about his whereabouts and only this Sunday received the news that he was murdered; he was executed at the age of 18 years: a young man who had the desire to become a man of God and his only sin was that he was a Christian.”

“Behold, the martyrs of the present,” Azbej said, calling the exhibit a reflection of this reality of persecution and “physical evidence of that very persecution, which is the greatest and the most concealed human-rights crisis of our time: the persecution of 260 million Christians worldwide.”

“The tyranny of political correctness makes sure to obscure the fact that on average eight people are killed each day for their Christian faith,” Azbej said. “It allows no mention of terrorist attacks against 9,000 churches last year. It turns a blind eye to the fact that the cradle of Christianity has become the graveyard of millions.”

Azbej said that the exhibition will “not only be merely a cultural program, but, more importantly, an experience of personal encounter with millions of tormented Christians, and this will hopefully provoke all of us to help those who are suffering.”

Rep. Jeff Fortenberry, R- Neb., remarked to those gathered that the international community must “elevate this first principle of human dignity and respect to create the space for tolerance again and that sacred space for conscience as it is expressed in belief systems.”

“We try to continue through this exhibit that the Hungarians have so generously funded to put these images before the world,” Fortenberry said.

Joe Grogan, the director of the Domestic Policy Council at the White House, commented at the event that the persecution of Christians has been ignored “for too long.”

“This is an issue we want to partner with Hungary on,” Grogan emphasized, as Azbej announced a recent partnership between Hungary’s aid group “Hungary Helps” and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to rebuild the Christian town of Qaraqosh in Iraq’s Nineveh Plains region.

Jeffrey Kloha, chief curatorial officer at the Museum of the Bible, told those in attendance that the museum was “honored to host this special exhibit to help our visitors and other people understand the needs in the Middle East and also to thank the Hungarian people for the support that they’ve given to those people.”

Rebuilding in Iraq and Syria

Following his remarks, Azbej told the Register about Hungary’s work to help persecuted Christians in Iraq and Syria through the program “Hungary Helps.”

“The most unique feature about our program is that despite being a government-run and managed program, we dare to work directly with Church institutions and faith-based charities,” he said. “There are not many, if any, governments who are doing that; they refer to so-called ideological neutrality, which we believe is false, because in these areas in the Middle East, usually it’s the Church institutions and the faith-based charities that can actually send a donation or benefit the most vulnerable minority communities.”

The Hungarian official said one of their biggest projects in Iraq was through their work with the Chaldean Catholic Church. “We have completely reconstructed a large village called Teleskov in the Nineveh Plains; it was completely devastated by ISIS,” but now, it has been “completely revived, and the three-quarters of the population that had fled Teleskov have returned, so, practically — together with our Chaldean brothers and sisters — we managed to save a community.”

He said the program is also “supporting, with the Chaldean Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church schools and clinics, the internally displaced community.”

Azbej said that the new partnership with USAID to rebuild Qaraqosh “will start with basic tasks like de-mining. First, we have to remove all the debris and the ruins; and then, on the second phase of our project, we will reconstruct houses for families and together with our American partners who have pledged to reconstruct shops to revive the trade in the city.”

International Awareness

Hungary has some joint initiatives with the Vatican, as well, and he credits the Holy See for proposing that “Hungary Helps” collaborate with the Italian Catholic charity AVSI to operate three Syrian Catholic hospitals for a year.

While working to give aid to the persecuted Christians, Azbej said, “The outlook and the prospects are very grim, and we are trying to save these communities. We are trying to enable them to remain in their homelands; but, personally, seeing how things are developing in the Middle East, I have no judgment whatsoever to those who lose hope. We are trying to have them create this hope, but otherwise it’s difficult.”

“It’s striking and it’s tragic what happened to Christianity in Iraq,” he said. “In 2004, the total number of Christians in Iraq was 1.5 million; according to the latest data we have now, it’s 250,000. It’s less than one-fifth, and you don’t need to be some sort of fortuneteller or politician who is trying to say something dramatic to see that if there is no international, immediate action, then the 2,000-year-old Christianity in Iraq will completely disappear in a few years.”

“This is why we are focusing there; and in Syria, it’s similarly tragic: Less than one-half of the original Christian population has remained in Syria,” he continued. “We do whatever a country that is only 10 million people can do, and we work, but we also pray. Perhaps the Christians can be saved in the cradle of not only Christianity as a faith, but also as the Christian civilization.”

Lauretta Brown is the Register’s Washington-based staff writer.

- Keywords:

- christian persecution

- hungary helps

- lauretta brown

- museum of the bible

- persecuted christians