Harney Peak Renamed for Sioux Catholic Convert Black Elk

Hiking up South Dakota's 7,242-foot Harney Peak, the highest North American point east of the Rocky Mountains, is one of our family’s fondest memories. My husband took the three oldest boys one summer and, a few years later, our entire family from teens down to a toddler in a backpack scaled it. We made it all the way to the beautiful old stone fire lookout on top. This past August 11, our beloved Harney Peak was renamed Black Elk Peak.

The craggy mountain emerges out of the Black Hills National Forest, three miles southwest of Mt. Rushmore. It was originally named in 1855 in honor of United States General William S. Harney. Recent criticism of him centered on his command of 600 troops in September of 1855, where 86 Sioux, including some women and children, were killed. The attack was in retaliation for the Sioux killing 30 soldiers and a civilian interpreter.

In later years, Harney participated in treaty talks in the South Dakota region. He became viewed as a protector of Indians, working zealously to honor promises. He even overspent his budget by $700,000. During modern times, however, the Lakota Sioux argued that it was offensive for the mountain peak to be named for one who had massacred their people.

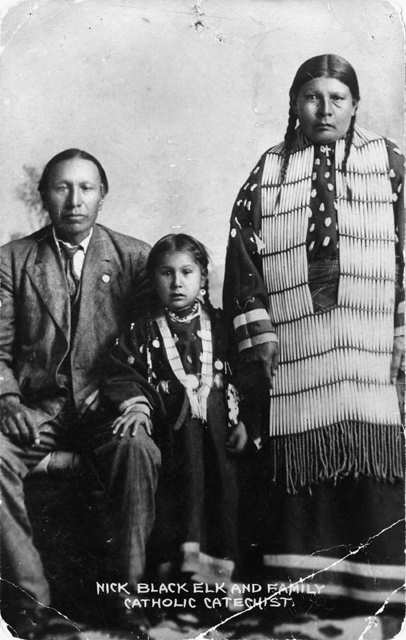

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names officially changed the mountain's name to "Black Elk Peak" to honor Black Elk, or Nicholas Black Elk (1863-1950), who was a revered Oglala Sioux holy man. He was also a devout and zealous Catholic. That part of his life is unfortunately often overlooked.

Zealous Catholic

Two of the first books to recount Black Elk’s life were Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux and Sacred Pipes. Both were based on conversations with Black Elk, but they focused on his life before the reservation, ignoring almost fifty years after his conversion to Catholicism in 1904.

In Black Elk: Holy Man of Oglala, author Michael Steltenkamp explained that Black Elk’s life in the 20th century as a Catholic was quite different from his life as a Sioux warrior and holy man in the 19th century. Steltenkamp was an anthropologist who taught for a time at the Red Cloud Indian High School on the Pine Ridge Reservation where Black Elk had lived most of his life. The author conducted numerous interviews during the 1970s with Black Elk’s daughter, Lucy Looks Twice.

Lucy said that her father became a Catholic missionary who had traveled with the Jesuits to help convert the tribes of Arapahoes, Winnebagos, Omahas and others. One missionary estimated that Black Elk was responsible for around four hundred converts.

His daughter expressed concern that people were using her father to push social actions and religious sentiments that he would not condone. Black Elk “meaningfully integrated new patterns of activity and lived out his days more or less happily,” Steltenkamp wrote.

Recognizing that some people wanted only to look at Black Elk’s pre-reservation days as a Sioux holy man, Steltenkamp explained, “Whatever perspective one adopts on this chapter of the man’s life, it needs to be understood that what seems a radically abrupt break with tradition is, at its core, an unfolding of reality that the holy man was predisposed to cope with, comprehend, assimilate, and address with considerable satisfaction.”

According to Lucy, her father embraced his new Catholic faith, and that is what ultimately brought him great respect among his people.

Integrated Old with the New

“I learned to my great astonishment that Black Elk’s prestige in the reservation community was not attributable to the popularity from his two books,” Steltenkamp wrote. “Prestige he had, but it was the result of his very active involvement with priests in establishing Catholicism among his people. Older persons remember him as ‘Nick’ Black Elk and most knew little (if anything) about the two books based on his life and thought.”

The former warrior did not pine away for the past, but embraced the new world around him. Black Elk actually traveled in the eastern U.S. and even Europe, joining Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show in 1886. His reputation as a Sioux holy man was used to attract crowds. Black Elk was also a second cousin to Crazy Horse and had been present during George Armstrong Custer’s last stand at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

It was Katie, Black Elk’s wife, who first converted to Catholicism and had their three children baptized. After she died in 1904, Black Elk also converted. He was in his forties then and began teaching others about the Catholic faith. Black Elk married again and his second wife and children were all baptized Catholic.

Steltenkamp took issue with the portrait in previous books that painted Black Elk as a melancholy ex-warrior. Instead, the mature Black Elk vibrantly embraced his faith whether praying the Rosary, building a chapel, or evangelizing his fellow Indians.

The author encountered repeated complaints from Black Elk’s associates that the media misrepresented him. They blamed the pressure for Native people to represent a certain image frozen in time, and not accepting that Black Elk willingly moved on.

In reality, although he is often remembered as a Sioux holy man, Black Elk’s conversion led him to disavow Indian ritual-healing practices. His life is an example of a convergence of the old with the new—keeping what was good from his heritage while he embraced his new life as a Catholic. “Lucy died on April 23, 1978,” Steltenkamp wrote, “consoled to know that the content of her father’s thought had been captured.”

[Note: A petition with over 1,600 signatures, to open the cause of canonization for Black Elk was presented to Rapid City Bishop Robert Gruss on April 16, 2016.]