Day 3 in #HolyJordan: Our Faith Builds on the Holy Land’s Living Stones

The Register's Peter Jesserer Smith is on a Year of Mercy pilgrimage, Oct. 7-15, in the Holy Land of Jordan.

Walking in the Holy Land means a pilgrim experiences an ancient living faith. A pilgrimage to the Holy Land is not a “faith journey” to an outdoor museum of dead rocks. Rather, a pilgrimage here involves a personal encounter with the area’s Christians, who are the living stones on which our faith is built, because they are our witnesses. The Christians of Jordan not only live in this land, but their presence testified that the story of our Salvation happened in a real place, to real people, their ancestors who “knew the gift of God,” embraced it from the apostles, and passed it on to their descendants for 2,000 years.

On this pilgrimage we worshipped with our fellow Catholics in Jordan. On Saturday evening, we went to the Christian town of Fuheis, about 20 kilometers north of Amman, and joined with our Catholic brothers and sisters at a Latin Rite parish. The priest and people sang the Mass in Arabic, and because the form was the same, I could follow along, and join in at key moments, such as the “Kyrie,” “Alleluia,” and of course, “Amen!”

Of course, I could also hear the prayers of the Mass directed to “Allah” (the Arabic word for God).

But the Latin Church is a Western Church of the Catholic Church. Remember, the Catholic Church is a communion of 24 individual, self-governing Churches of equal dignity that have unity with the Bishop of Rome. So why is the Latin Church in Jordan, the traditional territory of the Eastern Churches that come from Jerusalem?

The short answer to that question, which we learned from one of the Latin Catholic priests in Fuheis. was that when Pius IX re-established the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem in 1847, he gave it a mission to establish Catholic schools in the region. After a number of Arab Christians had been educated in the schools, some Arab tribes decided to switch from Eastern Orthodoxy to Latin-Rite Catholicism. And to this day, the priority remains for Latin parish communities: if you have to choose between operating the church or operating the school, you keep the school open.

But on Sunday, we joined our fellow Catholics, the Melkite Greek Catholics, for Divine Liturgy at the old cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. As a Latin Catholic, I’m less familiar with the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom — readers may want to know that “Mass” is the Latin Rite’s name for their particular Church’s Divine Liturgy — but the rich texture of the priest and people chanting in Arabic — without musical accompaniment — was just amazing and so spiritually uplifting! While moments of silence are part of the Latin liturgy, the Eastern liturgy is very rich in the senses, with bells, incense, chanting, ritualized movements through the sanctuary, etc. — all designed to immerse the heart, mind, and body in the presence of God.

We felt very warmly welcomed by the pastors at both the Latin and Melkite parishes. But at St. Peter and Paul’s, Father Nabil Haddad offered up the Our Father in English, allowing us to join our voices in the Divine Liturgy. At both churches, but particularly at the Sunday Divine Liturgy, I felt this deep bond and closeness with our Catholic brothers and sisters, who made me feel right at home with their warmth and hospitality.

The Church is Alive in Jordan

I plan to write more about this when I get back, but in Holy Jordan, you get the unmistakable sense that the Church is alive here. But you get a deep sense of solidarity and closeness that you would not otherwise experience. As Father Nabil pointed out, the Christians of Jordan also need our closeness: our solidarity can’t be just donations, or support from afar. We need to go there, share our lives, and have fellowship with them.

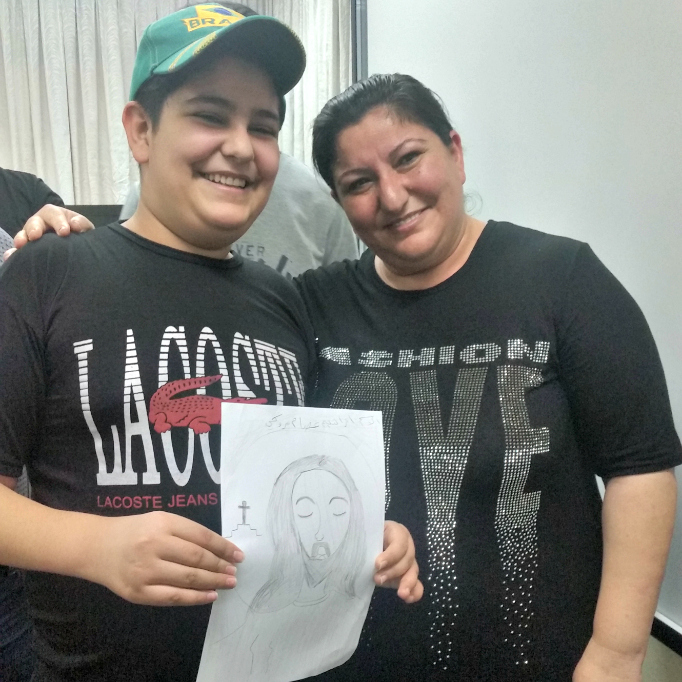

The Church is alive in Jordan, evangelizing with its witness to the Gospel by building up Jordanian society and helping those most in need. In Amman, the Teresian sisters run the Pontifical Mission Library, which is an important community center and place of learning, for both the local community (such as these girls below) and the refugees in the country.

But here, I experienced perhaps one of the most precious, but most difficult moments of the trip: visiting with the Christian refugees from Iraq.

I had visited with Iraqi refugees in Oct. 2014, just months after ISIS came in and uprooted their lives. Two years later, they are still in limbo: doctors, teachers, lawyers, engineers, IT professionals, businessmen — all penniless, completely dependent on the generosity of others, and just wanting to resume a “normal life” in a safe country. My journalistic colleagues were shocked by the stories they heard — and while it was not the first time I had heard their stories, I found it just as hard. Even more than that, I felt inadequate before their anguish and their loss.

You can’t begin to imagine what they have endured unless you start to think about what would happen if you had to walk out of your house, with only your family and the clothes on your back. You have to cover 50 miles by foot with your children, parents, and grandparents. And you make this painful choice, because rejecting Christ is so horrible, it is unthinkable.

We Need Them, They Need Us

The world has largely forgotten these Christians. They are living in limbo, because refugees cannot legally work in Jordan. Old parents are along now; young men and women cannot marry and start families; parents do not have the joy of becoming grand parents, etc. etc. They want a new life; they wonder “when shall we go to [America, Canada, Australia, etc.]?” But hardly anyone from the United Nations returns their phone calls. Months have turned into years — what will the years turn into?

The Iraqi Christian refugees depend completely on the generosity of the Church to survive. Most of them are Chaldean Catholics. I spoke with a grandfather who had eight children with his wife, and has three grandchildren. They are all living together in a tiny apartment. They can’t afford anything else.

These Christians need us and our support — we need them and their faith. They are the face of why the Church asks us to tithe — 10% or more is the biblical ideal according to the Church fathers — because only when we give back to God from our substance, can the Church support them. And that brings real joy.

When you look into the eyes of a Christian refugee, you see your own reflection — and it can hurt, because you are in the presence of those most precious to God, and you know you don’t measure up. But you want to measure up. So what do you do? In my case, I asked them to pray for me. And I promised to pray for them. I think that is the place we need to start.

Prayer is the door we open inviting God to come into our hearts with his mercy. In this Holy Land of Jordan, I pray for the grace of Jacob — and the Iraqi Christians — to hold fast to the Lord in the dwelling of my heart, and never let him leave.

- Keywords:

- #holyjordan

- #yearofmercy

- holy jordan

- holy land

- holy land pilgrimage

- iraqi christians

- jordan

- middle east christians

- pilgrimage

- year of mercy

- year of mercy pilgrimage