Day 2 in #HolyJordan: Stories of Embracing and Rejecting the Lord’s Mercy

The Register's Peter Jesserer Smith is on a Year of Mercy pilgrimage, Oct. 7-15, in the Holy Land of Jordan.

Today my pilgrimage in Jordan offered a powerful contrast for the Year of Mercy. At two holy places today, I was reminded that we have two choices with Jesus: we either will embrace him, or we go out to the Lord and tell him to go away.

Two stories that took place in Jordan, separated by more than 1900 years, illustrate this contrast in our approach to God’s mercy: Jacob the patriarch at the Jabbok river (also known in modern day as the Zarqa river), and Jesus Christ at Gadara.

The Jabbok river is a fast-flowing tributary of the Jordan river. In the sunlight, the river looked almost like water flowed over a bed of golden coins. Here, at the ford of Jabbok, Jacob “wrestled with God” and received his name Israel.

What Jacob at Jabbok and Arab Hospitality Teaches Us

But the context of that story tells so much more about the narrative than the text itself. Our guide on this tour, an Arab Catholic, explained that Arab tribal culture has unwritten laws and regulations of hospitality, which explain the drama going on. He gave us an example: if you visit your relatives, they will likely offer that you have lunch with them — but you really just can’t refuse. You cannot say “no thank you,” even if you have an important meeting. They will keep insisting until the end of the world (and beyond) until you have lunch with them. They will hold on to your shirt and refuse to let you go! So, culturally speaking, the only way to leave and get to your meeting is to have lunch with them, even if it is just a symbolic bite of a sandwich, to fulfill the demands the law of hospitality places on you both.

Well, something similar is at work with Jacob. He spends all night wrestling with a mysterious “man” (is he an angel sent by God, or a theophany of God himself — it seems unclear), and won’t let go. This “man” even busts Jacob’s hip — an injury from which he never recovers — and Jacob still refuses to let go. Finally the “man” tells Jacob to let him go “for the day is breaking.” But Jacob is still tenacious and says he will not let go “unless you bless me.” And this way, Jacob gets both a blessing and a new name, Israel, meaning “He who wrestles with God.”

But Jacob at this river showed how we have to approach Jesus. Jesus says that he knocks at the door, but our response needs to mirror the Arab tribal rules of hospitality: when the open the door, we must not only let Jesus come into our homes, but we must embrace him so tightly — just like Jacob — that he has really “no choice,” so to speak, than to abide with us. He wants to stay with us, and we do not want him to leave. Jesus no doubt has this culture and its laws of hospitality in mind, when he says in Revelation: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if any one hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and eat with him, and he with me.”

So Jacob provides us an example of how when we cling to God, the Lord gives us the blessing of his mercy.

But what if we’re not like Jacob? What if God comes to our home, bringing with him his wonderful gift of merciful love, and we meet him at the door — and ask him to please “go away?” And the quicker the better! Because we can’t have his presence upset our plan to conduct life on our own terms. Maybe we tell him to go away “politely,” but the effect is still the same: refusing hospitality is a terrible insult.

Jesus at Gadara: Good for Souls, Bad for Business as Usual

Later in the day, we went to Umm Qais, which is near the ruined city of Gadara. This brings us to the story of Jesus at Gadara casting out the demons from two demoniacs described in Matthew. Jesus crossed the Sea of Galilee, and encounters two men, living among the Gadarene tombs, and they are possessed by many demons. The demons know how this fight with the Son of God is going down, and sue for terms, asking to be cast out into a nearby herd of swine — unclean animals in the Jewish tradition. Jesus agrees, the demons flee into the swine, but the funny thing is that they cast the entire herd off the cliff (you can see it in the photo, it’s the promontory jutting out on the left with an incredibly steep drop) into the sea to perish.

The demoniacs are liberated! The way by the tombs is safe again! And what do the Gadarenes do when they learn of this mighty deed of Jesus? Matthew says the entire town came out, and tells Jesus to go away.

No welcome party. No hospitality. No thank-you. Just leave. It’s a huge insult for a hospitality-based culture, even for Hellenized pagans in Gadara.

But why did this happen? Well, for one thing, it is because the priorities of the heart show how we treat Jesus. You see, Gadara was a very wealthy place. From their point of view, Jesus had not just exorcised two demoniacs — he just devastated the local pig farming industry. A culture that values economic gain above human life and dignity does not find Jesus someone to celebrate.

What We Can Learn from the Gardarenes Falling for the Demonic Trick

I don’t think the demons were stupid when they asked Jesus to be sent into the pigs near the cliff. Actually, only when you’re standing there on Gadara’s acropolis does the demons’ request finally come into perspective as a cunning set-up for tempting the Gadarenes. It just hits home again that the devils are nobody’s fools. Here’s why: the steep cliff is in plain sight of the city, so a thundering herd of suicidal pigs would be hard to miss. Obviously, the demons didn’t want the Gadarenes to hear Jesus’s preaching, and it seems reasonable to conclude they knew the spectacle would tempt the Gadarenes to send Jesus away, because he’s bad for their business. Which is exactly how it played out.

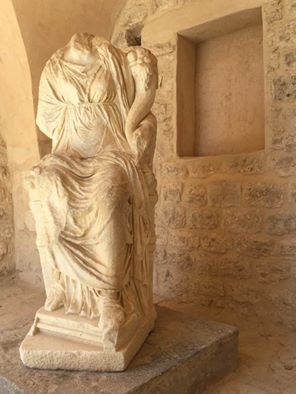

You see, Gadara is a pagan city, but it is a wealthy trading city built at a commanding point on the King’s highway. At the ruins today you can see the main thoroughfare into the city, lined with pillars, also known as the Roman “cardo,” the remains of two amphitheaters, a temple, and the necropolis. It had great wealth and an established way of doing things — and Jesus would upset that. They valued wealth over the sacred rules of hospitality, and turned away the Son of God.

Why did Jesus allow them to have this temptation? I think the Lord not only intended the Gadarenes to choose what really mattered, but he also wanted us to examine what our hearts truly treasure.

Think about that: the Gadarenes turned away the Mercy of God in the flesh. For what? The things of this earth? Their city is ruins, and their money is gone. What a poor exchange in the end for the Gadaranes. What remains truly — and you truly feel it in your bones when you’re walking in this Holy Land — are the words of Jesus Christ, who has the words of eternal life.

“Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away.” ~ Matt. 24:35.

Please feel free to use the combox to ask me to pray for any special intentions while I'm on this pilgrimage. And please pray for me as well!

You can read here Day 1 of my pilgrimage to Holy Jordan.

- Keywords:

- #holyjordan

- demonic possession

- demons

- gadara

- jabbok river

- jacob

- jordan

- peter jesserer smith

- year of mercy

- year of mercy pilgrimage