Created Equal: 12 Quotes on Racism from Justice Clarence Thomas

“I decided that the principles on which I was raised — the principles of this country,” says Justice Clarence Thomas, “were worth dying for.”

We are in a unique time in history. The tragic death of George Floyd at the hands of a white police officer is fueling protests, some violent riots, and the toppling of statues all in the name of justice and equality for all.

Justice Clarence Thomas, the only African-American member of the U.S. Supreme Court (and who celebrates a birthday this week), has also experienced the same anger at the problem of racism in this country. As a college student, Thomas became a member of the Black Power movement.

As the high court completes its term issuing decisions in a number of closely watched cases, here’s a look at some of Thomas’ own observations and insights on racism in America — and how he has chosen to deal with it.

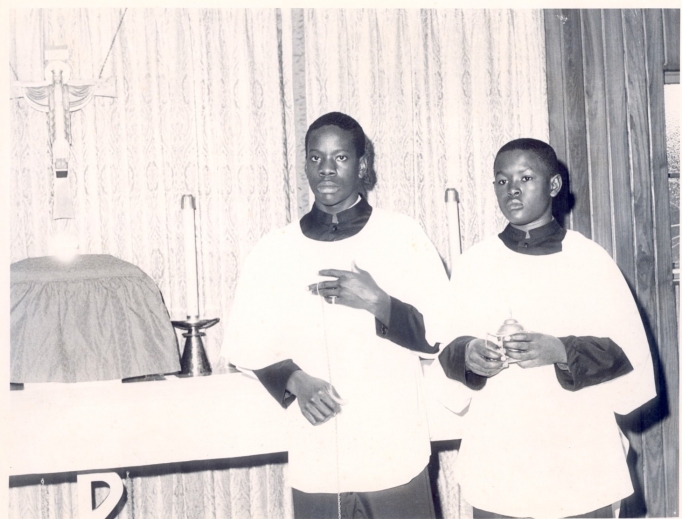

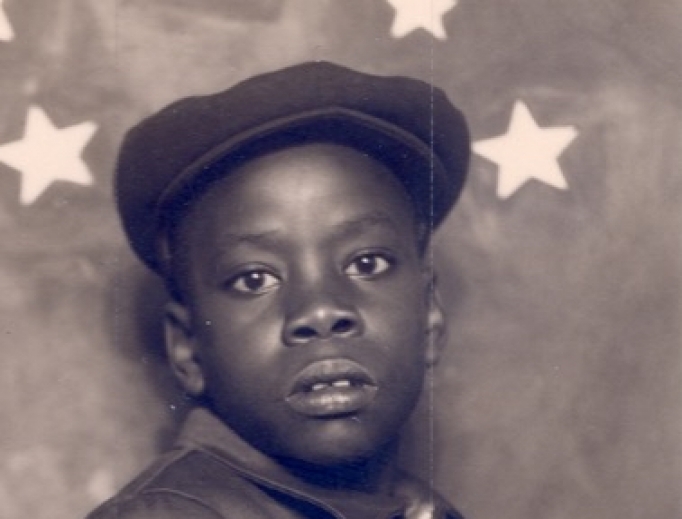

Gleaned from a new documentary released this year, Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words, shows one man’s painful confrontation with racial bias and his struggle to come to grips with it in his own conscience. The justice’s earliest ancestors were slaves dating back to the 18th century. Growing up in Pinpoint, Georgia, Thomas lived a poverty-stricken life in the segregated South. As he was fatherless, his mother made the wrenching choice to let Thomas and his brother, Myers, move in with his grandparents. His grandfather, stern and rigid, minced no words on the day they moved in: the vacation is over.

It was in his grandfather’s house that Thomas began to develop his own response to life in the Jim Crow south. From his primary years learning from Catholic nuns in a school with segregated classrooms, to his shocking experience with racism while attending seminary, the evolution of the justice’s thoughts about himself, race, and God took many twists and turns.

In Created Equal, Thomas underscored a key element of his character.

“I was born at home, right on Shipyard Creek in 1948. My mother always said I was too stubborn to cry, and I guess that was a sort of indication of the kind of person I would be."

After moving in with his grandfather, Thomas chafed at his disciplinary regime, yet that stubborn streak led him to resist racial bias and low expectations for black students. As an adolescent, he was determined to excel in the classroom.

“You assume you’re going to be discriminated against. So I can't get a 98 ... I have to have 100. In other words, to leave them nothing but race. It's sort of like ‘checkmate.’”

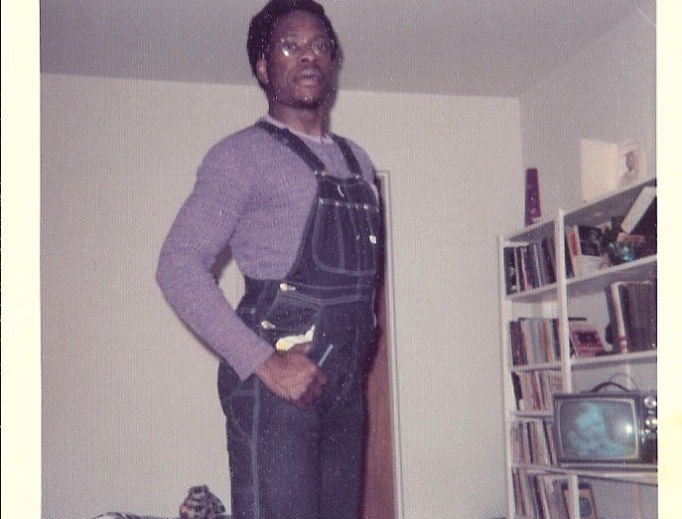

But his impressive academic record could not protect him from racial slurs. The only African American student at a Catholic seminary, he was shocked when a classmate openly disparaged the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Ultimately, Thomas left the seminary enrolling in the Jesuit-run College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. There he embraced the Black Power movement.

"And for the first time in my life racism and race explained everything. It became, sort of, the substitute religion; I shoved aside Catholicism and now it was this, it was all about race."

The scope of racism stirred anger in him, and some of it was deflected towards his grandfather. Thomas found himself lashing out on all that had shaped him.

“I’m angry with my grandfather. I’m angry with the church. If it’s a warm day, I’m angry. If it’s a cold day, I’m angry. I’m just angry.”

One fateful night after a protest that turned violent, Thomas wandered into a church and found himself pleading to God.

“If you take this anger out of my heart, I will never hate again.”

After this conversion of heart, Thomas began to see how the life of his own grandfather was shaped by the brutal and routine experience of racism.

“You couldn’t walk across certain parks: you couldn’t go to certain schools; people’s property being taken; people taking advantage of him [my grandfather] because they could say ‘the law did this’ or ‘did that.’ So I decided I was going to go to law school.”

He had a found a new vocation as a lawyer and enrolled in Yale University Law School. But he was under no illusions.

"If you were black, and you were at Yale, the presumptions were quite different.... If you're white, and you graduated from Yale, the presumption is that you are among the best. On the other hand, if you're black and you're there, you didn't quite belong."

During his time in law school, Thomas begins searching for where he does belong.

"I was never going to be a part of that world; I was never going to be white. The problem is I could never go back completely to the world I came from."

He had reached a new crossroads. He knew racism was real but he was drawn to a different path of study and reflection. He became committed to libertarian and conservative principles. And as he became voluble in his beliefs, he faced what he saw as another form of racism: political liberals who attacked him for refusing to share their beliefs. After joining the Republican party, and was later appointed to senior posts in both the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations, he was accused of betraying his people.

“Any black misguided enough to accept a job in the Reagan administration was automatically branded an ‘Uncle Tom.’”

“Any black misguided enough to accept a job in the Reagan administration is automatically branded an ‘Uncle Tom.’”

— Justice Thomas Movie (@JusticeCTMovie) March 23, 2020

—Clarence Thomas#CreatedEqualClarenceThomasInHisOwnWords pic.twitter.com/R5M6yNNyDx

After his service in two Republican administrations, Thomas was nominated to the Supreme Court. But his Senate confirmation hearing became a flash point in America’s culture wars when he faced accusations of sexual harassment.

At the confirmation hearings, he categorically rejected these accusations and fiercely defended his reputation. He argued that he was being punished for refusing to embrace Democratic party principles.

“This is a circus. It’s a national disgrace. And from my standpoint, as a black American, it is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to an old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree.”

Thomas was narrowly confirmed and has served on the high court for 28 years. His jurisprudence remains grounded in the founding father’s original intent for the constitution as written. In his memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, and elsewhere, he has affirmed his belief that the inalienable dignity and rights of all, regardless of skin color, “come from God” and not the state.

“They start with the rights of the individual, and where do those rights come from? They come from God; they’re transcendent. And you give up some of those rights in order to be governed. They’re inalienable rights. And you give up only so many as necessary to be governed by your consent.”

Thomas celebrated his 72nd birthday June 23, and while much has changed since his childhood growing up in the Jim Crow south, he acknowledges that racism is still a reality today. Yet as he makes plain in his memoir, Thomas loves his country.

“As much as I hated the injustices perpetrated against blacks in America, I couldn't bring myself to hate my own country, then or later.” ― Clarence Thomas, My Grandfather's Son