Surveying the Supreme Court Landscape After Justice Breyer’s Resignation

Legal scholars predict that the battle to replace the longtime justice will likely be less intense because the court’s status quo will remain unchanged.

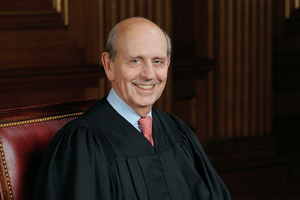

WASHINGTON — Amid a groundbreaking U.S. Supreme Court term that could end with the demise of Roe v. Wade, Justice Stephen Breyer announced his retirement, prompting President Biden to reaffirm his 2020 campaign pledge to nominate a Black woman to fill the lifetime appointment.

But even as the ensuing headlines signaled the justices’ powerful role in U.S. politics and culture, experts noted that the likely confirmation of a more liberal jurist would leave the conservative wing’s 6-3 supermajority intact, while Breyer’s absence could complicate efforts to secure narrow compromise rulings on high-profile cases.

“Filling an opening on the court has become a continuation of partisan presidential politics,” Gerard Bradley, a professor at the University of Notre Dame Law School told the Register, as Biden celebrated Breyer’s legacy and partisan forces positioned themselves for a rapid confirmation process.

“The justices are more to blame than the politicians” for this state of affairs, Bradley added, for “the court has seized an outsized role for itself which the justices should never have claimed for themselves.”

Social media lit up with partisan messaging and specific demands from activist groups calling for progressive candidates. However, legal scholars predicted that the battle will likely be less intense because the court’s status quo will remain unchanged.

“It’s like Gorsuch replacing Scalia,” explained Teresa Collett, a professor at the University of St. Thomas Law School. “Where we see open warfare is when [an appointment] moves the court significantly one way or the other. That, in part, is why Kavanaugh was so viciously attacked.”

Legal experts further noted that the resignation will have no impact on the outcome of the Mississippi abortion case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, that will be decided this term, with a groundbreaking decision expected by early July. Breyer has authored three landmark rulings that overturned state laws restricting abortion, and he is expected to rule against the Mississippi law, while the conservative majority on the high court will likely uphold the law and possibly go much further.

Based on the Dobbs oral argument, “it seemed that Breyer was very likely to vote to overturn Mississippi’s law,” said Carrie Severino, president of the Judicial Crisis Network. “I think that will be the losing side, but we obviously don’t know that for sure.”

The close of Breyer’s 27-year tenure on the court was formally announced during a Jan. 27 White House press conference. Breyer was present as President Biden thanked him for his “exemplary” service and then repeated his campaign pledge to nominate a Black woman as his first Supreme Court pick.

Biden declined to immediately identify his short list of Black female nominees to replace Breyer, but GOP leaders did not wait to register their belief that Breyer, widely characterized as a “moderate liberal,” would be replaced by a candidate approved by the “radical left.”

“The American people deserve a nominee with demonstrated reverence for the written text of our laws and our Constitution,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., stated in an opening response that echoed the criteria that has been used to identify top GOP judicial nominees, including President Trump’s three picks, Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Senate Majority leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., promised that Biden’s nominee would “receive a prompt hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee, and will be considered and confirmed by the full United States Senate with all deliberate speed.”

The Outgoing ‘Moderate Liberal’

Stephen Breyer took his seat on the high court in 1994, after winning confirmation on a 87-9 vote. A San Francisco native who graduated from Stanford University and Harvard Law School, Breyer clerked for Justice Arthur Goldberg, and served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.

Seven years earlier, Senate Democrats led by Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts employed brutal tactics to smear Judge Robert Bork’s legal record and successfully block his nomination. That pitched battle marked the court’s increasingly dominant role in resolving contentious political debates on matters that had once been reserved for the nation’s elected representatives.

Still, the muted partisanship that smoothed Breyer’s confirmation seemed to carry over to his pragmatic, scholarly public persona.

Breyer “is one of the more moderate of the liberal justices,” Carrie Severino told the Register. “During oral arguments, he often liked to propose a pragmatic rather than a dogmatic outcome. He would say, ‘Well, can’t we all just get together and come up with some other solution?’”

“That’s kind of humorous,” Severino acknowledged, given that the litigants had already spent millions in a lengthy legal battle, and the time for pragmatic compromise had come and gone. “But he really did want to try to find a workable solution to get as many voices to the table as possible.”

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, Breyer broke ranks with his liberal colleagues on key religious freedom cases.

“Breyer was supportive of free exercise and opposed to establishment of religion,” Douglas Laycock, a leading authority on religious freedom at the University of Virginia Law school, told the Register, as he ticked off his votes in favor of permitting or even requiring government aid to religious schools.

“He frequently looked for compromise in key cases,” added Laycock. “Maybe his most significant religious liberty opinion is his concurrence in Van Orden v. Perry, providing the fifth vote to uphold the Ten Commandments monument on the Capitol grounds in Texas.”

Breyer explained the historical context for the creation of the 40-year-old monument, concluding that it was primarily designed to evoke a secular message about moral conduct, with no explicitly religious meaning.

“That was an intuitive, fact-intensive opinion; it did not make a whole lot of sense in terms of either the plurality’s legal doctrine or the dissenters’ legal doctrine,” said Laycock. “But it minimized the hostile popular reaction.”

Yet for all the respect accorded Breyer’s preference for moderation, he remained an unwavering supporter of abortion rights and same-sex “marriage.” And reproductive rights activists have celebrated his role in authoring majority opinions that overturned state laws restricting abortion, like Stenberg v. Carhart, which struck down Nebraska’s ban on “partial-birth” abortions.

In 2016, Breyer penned the decision in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, which overturned a Texas abortion law that imposed restrictions on abortion businesses and the physicians who performed the procedures. And in 2020, he authored another decision that struck down a Louisiana abortion law with similar provisions.

Employing his “fact-intensive” approach to such questions, Breyer sought to offer a kind of cost-benefit analysis that balanced the law’s stated goal of improving patient safety against the “undue burden” that the provisions reportedly imposed on women seeking abortions.

Meanwhile, his rulings on cases that addressed the newly ascendant campaign for LGBT rights consistently hewed to a progressive framework, though he might express a measure of skepticism during the court’s public proceedings.

During the 2015 oral arguments for Obergefell v. Hodges, Breyer pressed the lawyer representing the same-sex couples to explain why “nine people outside the ballot box [should] require states to change” laws that had defined marriage as a union of a man and women for “thousands of years.”

Nevertheless, he ruled with the majority in the landmark decision, legalizing civil gay marriage nationwide, and again in the court’s 2020 decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, which held that Title VII anti-discrimination provisions in employment also applied to workers who identified as gay or transgender.

“If Justice Breyer enjoys a reputation for ‘moderation’ compared to, say, Justices Ginsburg or Sotomayor or Stevens,” said Bradley, it is due to his “more scholarly demeanor and his often temperate-sounding comments about the role of the court in American society.”

“The substance of his positions has been anything but moderate,” Bradley added. And thus, his replacement is unlikely to “change the outcome of any case of special interest to those who care about maintaining religious freedom, preserving life and protecting the family.”

Breyer’s impact on the court’s jurisprudence will shift into sharper focus after he retires, and Biden’s nominee makes her mark on the court.

President’s Pledge

At present, the White House has yet to provide a list of Black female jurists under consideration, though it has confirmed that U.S. District Judge J. Michelle Childs, 55, of South Carolina, is on the short list of candidates. Both GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham, a member of the Senate Judicial Committee, and Rep. James Clyburn, the third-ranking House Democrat, have registered support for their fellow South Carolinian.

Other candidates noted in media reports include California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger, 45, and U.S. Circuit Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, 51.

Democratic activists and Black legal scholars and advocates have celebrated Biden’s pledge to confirm a Black woman, while lobbying for more specific objectives.

Demand Justice, the powerful progressive group that has campaigned for an expansion of seats on the Supreme Court that would dilute the votes of conservative justices, argued on Twitter that the selection of Judge Jackson, a former public defender, would advance the goal of “professional diversity” on the court.

Other Democrat voices have focused on the political significance of Biden’s pledge.

The administration “recognize[s] that Black voters are the ones that took them to the White House,” Nadia Brown, a professor of government and director of women and gender studies at Georgetown University, told The Washington Post. “And now that they know that they’re going to be key to making sure that the Biden agenda has a chance at passing.”

GOP lawmakers and conservative judicial activists like Severino, a veteran of Supreme Court confirmation battles, have challenged the thrust of the Democrats’ messaging.

“It’s not, ‘We need a judge who has a specific interpretive framework, one that would be in contrast to originalism,’” Severino told the Register. “They are saying, ‘We need justices who are going to stand up for environmental justice or women’s rights.’ They are looking for a specific policy goal.”

Likewise, she objected to the increasing prominence of identity politics in the search for a new justice, a shift that would appear to downgrade traditional professional criteria used to identify and evaluate leading candidates.

A number of legal experts and GOP lawmakers have raised similar objections. The pool of Black women jurists listed in media reports “are all worthy candidates who could have been considered for any vacancy without declaring that they were qualified by virtue of filling a quota — an unfortunate implication for the ultimate nominee,” wrote Jonathan Turley, a law professor at George Washington University in an opinion column for The Wall Street Journal.

The White House has sought to deflect such criticism, while progressive activists hope the pushback won’t cause centrist Democrats to withhold their support. Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona have already broken ranks with their party over its efforts to expand the number of seats on the Supreme Court, and eliminate the chamber’s 60-vote threshold to break a filibuster, a stance that prevented Democrats from securing major voting rights legislation last month.

“I’m very grateful that both of them did stand firm against the court packing efforts, and, in particular, against the elimination of the legislative filibuster,” said Severino.

But she is doubtful that the two Democrats would oppose Biden’s choice, noting that they voted with their party last December to secure the confirmation of Jennifer Sung, the president’s controversial pick for the Ninth Circuit who squeaked through a 50-49 floor vote.

Senators Manchin and Sinema have approved “every judge that Biden has put forward so far,” she said, “raising questions that they would be willing to stand up and express concerns in the high-profile stakes of a Supreme Court vacancy.”