Why Faith and Reason Go Together

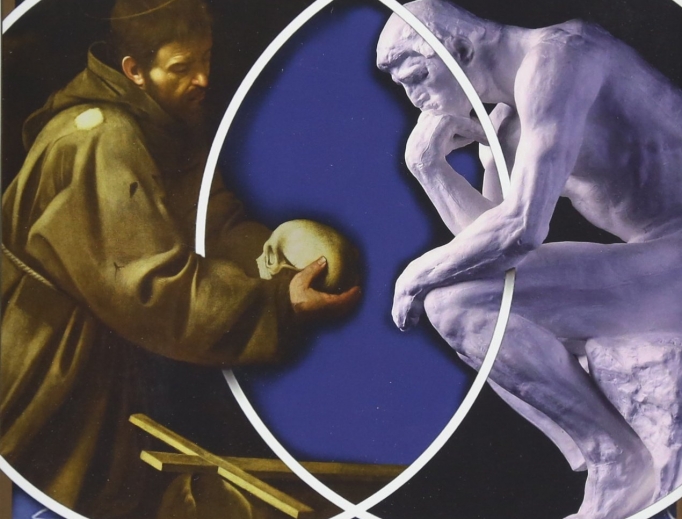

BOOK PICK: Two Wings: Integrating Faith and Reason

TWO WINGS

INTEGRATING FAITH AND REASON

By Brian B. Clayton and Douglas Lee Kries

Ignatius, 2018

$18.95, 285 pages

To order: ignatius.com or (800) 651-1531

How faith and reason are related — compatibly or conflictually — has fueled debate for millennia. Indeed, in a certain way, one longs for that debate: Today’s “whatever” betrays intellectual sloth too lazy to reason and too indifferent to believe.

That’s where this book comes in. Clayton and Kries, professors of philosophy at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, wrote this very readable yet intellectually rigorous introduction to how faith and reason might go together. They admit to being “integrationists,” i.e., that in some way faith and reason can be brought together harmoniously.

But why bother? The four parts of Clayton and Kries’ book detail just what’s at stake.

Part I examines ways of understanding the faith/reason relationship. It uses everyday examples to show how normal people apply both in everyday life. (Next time you take a friend’s recommendation about a restaurant or stock at face value, ask if you are not a believer.) Part II asks whether God’s existence can be rationally established (e.g., by arguments based on contingency or causality) or denied (e.g., by the existence of evil or the plurality of religions). Part III takes on directly the challenge of science: Do modern physics and biology (especially evolutionary biology) underpin or undermine faith? Part IV surveys how the faith/reason relationship affects practical life, be it marriage and family, violence and warfare, or the model of the state.

The book originated as a Gonzaga class, and its systematic, methodical development of ideas is apparent. When a book’s primary illustrations are Venn diagrams, you’ve got a good clue about its academic genesis!

The writers’ twofold ambitions are great yet modest. They want “to enable the reader to understand the ‘lay of the land,’ to grasp what the basic arguments and principles are in this area of debate.” But, even more so, they want to revive awareness of just why that debate is important.

“We have come across a great many people for whom the question of the relationship between faith and reason is no longer a question. Sometimes they are fideists who think that reason can have nothing to say about such matters; more often they are rationalists who have unreflectively accepted the notion that faith is simply irrational. We find it disheartening that so many otherwise decent and intelligent people find themselves in such a close-minded position.” Or, even worst, dismissing it as “whatever.”

Adapting professor Charles Kingsfield’s famous line from the old Paper Chase series, readers of this book teaches themselves about the issues, but Clayton and Kries train their minds. “You come in with a skull full of mush; you leave thinking like a” human.

If I had an unfulfilled hope about this book, it was from a suggestion broached early on: Comparing Socrates as an example of reason and Abraham of faith, the authors note “both are great lovers. This incredible desire and longing for something greater than oneself is common to both great thinkers and great believers.” I would love to see an orthodox take on Pascal’s “the heart has reasons of which reason knows nothing.”

I recommend this book especially to two groups: General readers who want the two sides of their lives — faith and reason — to work together will find it rewarding. College students who, in the contemporary milieu, often come to think that faith is irrational at best and superstitious at worst need this book.

We can hardly expect people to take faith seriously when their professional competence is sophisticated but their religious and philosophical formation rudimentary: No car runs well with an underinflated tire. I’d make it a gift to college-bound students, with the advice to “think about it over the next four years,” as well as for college graduates for “what you probably didn’t learn but should have.”

John M. Grondelski, Ph.D., writes from Falls Church, Virginia.

- Keywords:

- book picks

- faith and reason

- john m. grondelski