Holy Quiet: Bethlehem Hermitage Offers Silent Oasis in Garden State

About 50 miles northwest of bustling Manhattan city sidewalks, solitude awaits peace- and prayer-seekers.

The Hermitage is tucked behind a quiet forested landscape of thick pine trees and open fields on 18 1/2 acres in a rural enclave, a scene all the more extraordinary for being located in the most densely populated state in the union — New Jersey. As a foundation of Catholic hermits for men and women, the Hermitage exists in the spirit and teachings of the Desert Fathers and Mothers of the early Church.

On March 5, 1975, the Hermits of Bethlehem were established in Chester, New Jersey. Today, the small colony of four professed female hermits, one brother hermit preparing to be professed as well as two sisters in discernment live here in simple cabins, set apart in a laura. That’s the Ancient Greek word to signify a pathway, in the tradition of their patron, St. Anthony of Egypt, and the other early monks of the fourth century A.D., who followed him willingly into the desert during a period of moral social decay in surrounding urban centers.

This latter-day pathway in the heart of the Garden State leads members of the Hermitage directly from their cabins and life of daily prayer, work and solitary silence to the chapel at the community house. The Hermitage has modern conveniences like plumbing and electricity, but the hermits shun television and social media and other worldly distractions.

“Guests on retreat will leave behind notes saying how happy they are to have visited here,” said Sister of Christian Charity Mary Margaret Miller, appointed in July 2016 as the episcopal delegate for the Hermit Sisters of Bethlehem Hermitage. “Our Lord really touches them.”

While Sister Margaret Mary recently accepted a new post with her order unassociated with the Hermitage, she has seen the Lord’s work being accomplished in her interaction with the Hermit Sisters, she told the Register.

“One of our new sisters, in discernment for a vocation as a hermit, said she thought she had died and gone to heaven when she came and experienced our laura,” Sister Mary Margaret said.

“Even the natural beauty of this place has touched her deeply.”

But this is not always a simple equation of swapping the frenzy of the workaday world for silence. “Solitude has a way of forcing things out in some people’s lives that all of a sudden may come to the surface — and that can be difficult for some to handle,” said Sister Mary Magdalene, 78, a hermit here since 1995, attired in the laura’s required traditional blue-and-gray habit.

“You may be dealing with a lot of personal stuff and challenges from your past,” added Sister Magdalene, delicately. “And you have to deal with it here because there are no distractions. You can’t go to the mall, or go to a restaurant to escape. And some people have a really hard time with that.”

Most visitors settle in well — as retreatants are expected to have made a previous silent retreat. Occasional snatches of conversation, sometimes for practical purposes, break the silence in the laura.

Sister Magdalene recalled one nurse who came on retreat from New York City. “Two or three hours after I had accompanied her to the hermitage, she was packing up to go back home — she could not handle the solitude,” she said.

I am sitting with Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Mary Magdalene in a modest dining room for guests, the bright summer’s day visible outside the large windows lighting up the room. There is a year-round Nativity scene in one corner and on the wall a traditional image of the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph. We are surrounded by an abundant sense of peace and industry in this rural paradise. The property abuts the Hermits of Our Lady of Mount Carmel on adjoining lands, expanding the zone of holy quiet.

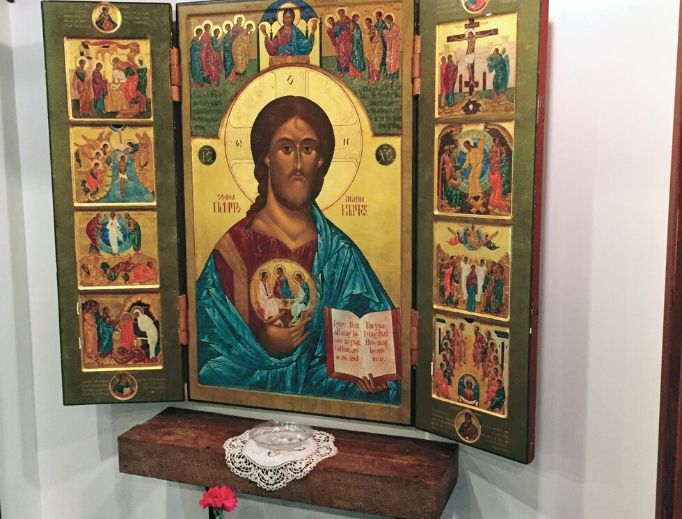

Touring the mostly timber-framed properties at the Bethlehem Hermitage, I notice that religious iconography fills places of gathering and worship. We pass a portrait of the Sacred Heart, donated by friends of Father Eugene Romano, a priest in the Diocese of Paterson who was raised in Madison, New Jersey, who started the Hermitage in 1974, on land donated by Chester resident Frank Van Alen.

We are introduced to a sister in discernment, happily sweeping a pathway, as the Angelus bell strikes for noon. We all pray together, and, afterward, I look around. A recent storm felled a section of the forested area. After we inspect the damage, we continue walking through the forest until it eventually reveals a vista of open fields. “A neighbor wondered if maybe we would plant some corn there one day,” said Sister Mary Magdalene, hinting with a smile that the fields will remain unplowed.

The pace of change is now more sharply defined than it was when the Hermitage first opened. “The old ways and traditions in our Church are considered passé by some,” said Sister Magdalene. “But, fortunately, there are still many who support the old ways and Catholic faith and traditions. I studied at Franciscan University of Steubenville, a wonderful Catholic institution of learning — and I am delighted it is still going strong and keeping our faith alive.”

Bethlehem Hermitage is more than ever a study in sharp contrasts with the modern world. “Father Romana told Bishop Casey, back in the 1970s, that everything everywhere was then becoming so busy — even many houses of retreat were becoming much more like places of dialogue — and there was very often not enough silence anymore for people on retreat,” recalled Sister Mary Magdalene. Bishop Lawrence Casey was then the leader of the Diocese of Paterson, serving from 1966 to 1977.

After approval for the Hermitage was granted in 1974, the turning point came on Christmas night 1982. Father Romano was alone in the Hermitage chapel when he felt the Lord moving him in a different direction, as Sister Magdalene recalled during this interview. Father Romano, now a resident in St. Joseph Home for the Elderly, in Totowa, New Jersey, told of a divine voice urging him to attract people to a consecrated life of solitude, poverty and celibacy.

That vision soon became a reality. By 1997, the Hermitage was canonically recognized as a “laura of consecrated hermits of diocesan right.” Father Romano’s constant prayer life, work and leadership are remembered with great fondness here. He returned for the 40th anniversary Mass and celebrations in 2015. “The hermit is one called by God in imitation of Jesus to live a life of unceasing prayer and penance in the silence of solitude for the praise of God and the salvation of the world,” writes Father Romano in a book he published on hermetical life, A Way of Desert Spirituality: A Plan of Life of the Hermits of Bethlehem (Alba House, revised edition, 1998). “It is a life lived in stricter separating from the world in the Heart of God and in the heart of the Church for the Church.”

The day starts here at the Hermitage in the wee hours, at 4am, and closes by 9:30pm, when the hermits have retired to their individual cabins. Before Mass and Eucharistic Liturgy at 8am, hermits live by a regimen of prayer, including an hour of Eucharistic adoration.

Until day’s end, the routine is devoted to prayer, contemplation and silence, with four hours set aside for manual labor, clerical and creative works, and studies. Hermits eat their meals alone, except on Sundays and solemnities, when they congregate for the main meal.

As this pleasant visit winds down, I call for opinions on why the Western world seems to be in the grip of moral chaos.

“Relativism is rampant,” said Sister Mary Magdalene. “I think it has to do with technology, too,” added Sister Mary Margaret. She would not call herself an enemy of technology, but she can’t help but notice how technology has consumed many people, seemingly in negative ways. “You see people wearing earbuds in public everywhere today, tuned into everything but the Holy Spirit.”

John Aidan Byrne writes

from New Jersey.

Bethlehem Hermitage

82 Pleasant Hill Rd

Chester, NJ 07930

Phone: (908) 879-7059

Website: BethlehemHermitage.com

- Keywords:

- hermitage

- john aiden byrne

- prayer

- solititude

- travel