Imagine Being Ordained, but You Cannot Tell Your Catholic Mother You’re a Priest

Father Tomas Halik on how Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia’s Catholic Church survived and came out stronger.

Czech philosopher and theologian Father Tomas Halik, secretly ordained in 1978 in East Germany (occupied by 380,000 Soviet soldiers), almost certainly the first new priest of Pope John Paul II’s papacy. For the first 12 years of his vocation (while 73,500 Soviet troops occupied Czechoslovakia), he worked in various civilian professions, the longest as a psychotherapist helping drug and alcohol addicts, who were unaware of his priestly status.

He also worked with Prague Archbishop Cardinal František Tomášek (1977-1991) who thought Father Halik was a talented lay Catholic. (Because Archbishop Tomášek was constantly under surveillance and his office bugged, Father Halik’s East German ordaining bishop thought it safest to keep the secret even from him.)

With the collapse of communism in Czechoslovakia, Father Halik was suddenly at the center of power. A friend of President Vaclav Havel (1993-2003), the priest was even mentioned as a possible successor. He participated in the revival of the Church as general secretary of the Czech conference of bishops. In 2014, Father Halik received the Templeton Prize, a prestigious award also given to Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and Mother Teresa.

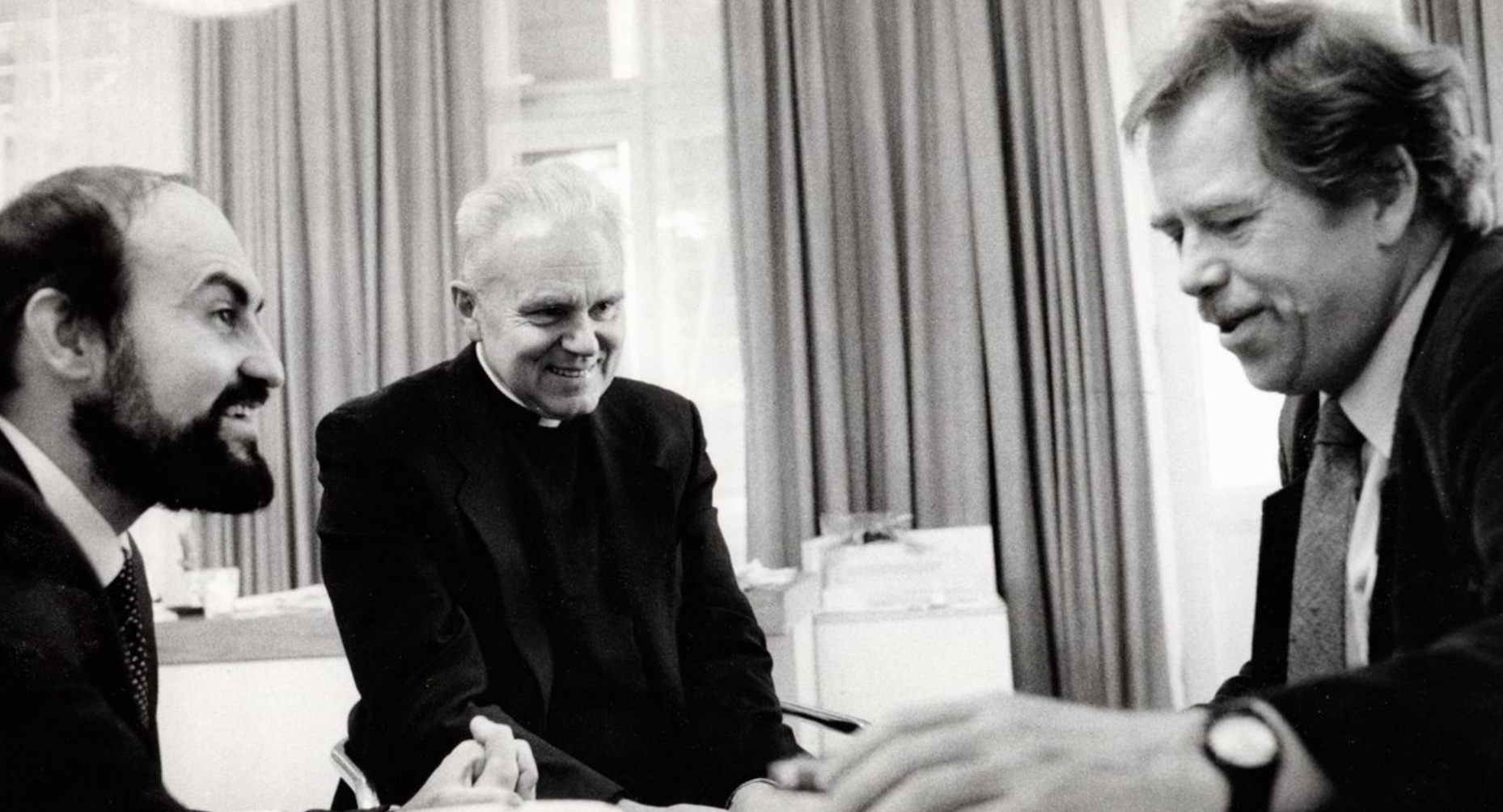

Left to right: Father Halik, Bishop Jaroslav Skarvada and President Vaclav Havel talk together in 1989.

Father Halik, a leading Catholic intellectual in Europe, is a professor at Charles University in Prague. Notre Dame University Press published his biography, From the Underground Church to Freedom, last year as well as a spiritual work, I Want You to Be: On the God of Love positing the importance of Christians serving nonbelievers. The Register recently interviewed Father Halik by phone from Prague.

Please tell me a little about how the underground Church was organized in Czechoslovakia?

There were several underground groups in Czechoslovakia. The rule was that nobody should know more than was absolutely necessary so the [state] police could not “knock it out of you” during an interrogation. So I knew a small group [of priests], but we did not know about others. Our group had a contact in Erfurt, East Germany, through Bishop — later Cardinal — Joachim Meisner, who traveled to Prague as an admirer of St. John of Nepomuk, a Czech saint.

When it was time for my ordination, he sent a postcard to one man in my group. It said, “The uncle can come on Oct. 22.” That was a sign for me to travel to a monastery in East Germany, where the Church had a much better situation. In our country, the monasteries were closed. Religious orders were forbidden.

The pressure on the Church was different in different communist countries. In our country, the Catholic Church was the major Christian community so it was much more suppressed.

I was touched to learn that you couldn’t even tell your mother, who you lived with, that you were a priest.

A mother’s heart always knows more than what is said in words. I didn’t want to worry her about my safety because I was practically living with one foot in prison. Today, she certainly knows everything in heaven.

Your own cardinal, with whom you worked closely as part of a supportive “brain trust,” did not know. Tell me how you eventually shared your secret with him.

Bishop Meisner (my bishop from East Germany), said, Don’t tell him anything. It’s better not to speak because it was dangerous in his palace, where everything was under surveillance. Remember, I owed obedience to Meisner as our contact with Rome. In 1988, I wrote a message on a piece of paper for Cardinal Tomášek, “Your Eminence, for over 10 years, I have been a priest clandestinely ordained abroad!” then I destroyed the note. He smiled, saying, “I thought as much,” and hugged me.

Cardinal Joachim Meisner (l) and Father Halik speak in 1990.

How many priests were ordained in secrecy in Czechoslovakia?

I’m afraid that nobody knows exactly. I count about 200, possibly as many as 300, between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, were ordained in East Germany and Poland.

At some point you write about the job you took with alcoholics and drug addicts who didn’t know that you were a priest. And you observed, “I realized I was in the right place, a priest should serve the poor, and those patients seem to be to me truly the poorest of our times.” Do you think this is still true today?

Yes, I think that all dependency leads to a lack of freedom. And these alcoholics and victims of drug abuse are losing step by step practically everything: health, family, job, self-esteem and so on. This dependence acts to destroy the person. It has a tragic effect.

Pope John Paul II traveled to Prague in April 1990, the first post-communist country he visited. You worked with the saint in Rome for a full month to help prepare this visit. In fact, you mention that when you met John Paul II to begin work, you were wearing, for the first time, a Roman collar and full cassock, which he proceeded to bless!

Tell us, what was John Paul II like? In your book you said he was one of the few men you ever met who “radiated” holiness.

So many things … he had a very fine sense of humor and an incredible memory. When I met him after two years, he said, “Oh, yes, last time we spoke about such and such,” despite having spoken to thousands of people between our conversations. And he knew all the names of our bishops. He also asked for news about so many people. So his memory was incredible. Most powerful was when I saw him during prayer. Before each meal, we went to his chapel to kneel before the tabernacle. I saw the Pope submerge himself in prayer like a stone falling into a deep well, and he seemed to be drawing us into those depths with him.

What were meals like? What did John Paul II like to eat?

Polish sisters cooked very simple Polish meals — very, very simple, with one sort of wine. I spoke with a French cardinal in Rome who said, “Oh, you will eat with the Holy Father, and there is just one wine for dinner. You know, it’s barbaric!”

After some 20 years when you could not travel, the world was suddenly your stage, and you traveled extensively. In your book, you described coming to the U.S. in 1994, invited by Michael Novak, and you wrote, “I realized American neoconservatism would not become my spiritual home.” What did you mean?

Under communism we were all enemies of communism and Marxism, and we had great sympathy for everything that was anti-communist. We were looking for some intellectual gurus. Michael Novak became one of them. He came to our country several times, and he was a very nice man. We became friends, and he had an influence on the Catholics in the ’90s. And then I came to the States, and I met Father Richard Neuhaus, a very charming man, and George Weigel was always friendly.

But step by step I realized something problematic, especially during the Iraq War catastrophe. Perhaps we were looking so hard for the antidote to communism that we were a little one-sided, so our admiration for neoconservativism weakened; especially when I studied more the social teachings of the Church — and then Pope Francis was, for me, something like another step in conversion. Here is a man bringing the light of the Holy Gospel into the Church again.

In our country Vaclav Klaus [prime minister in the 1990s and president of the Czech Republic 2003-13], was the main ideologue of wild capitalism, which I recognized to be like Marxism, just in reverse. It has the same economic determinism of the Marxists.

Wild capitalism assumes if we privatize, if we change the economic basis, everything’s good; culture and morality will follow automatically — we don’t need to care about the moral situation or a culture of law, for example. After the collapse of the regime, leading communists were still the only people who had financial capital, information and contacts. So many of the last communists became the first capitalists. They changed the ideology, but not their mentality.

They adored “the invisible hand of the market,” but they introduced the invisible hand of corruption.

Capitalism does not work automatically to promote a moral atmosphere. It is not so easy to convert people from the so-called Soviet men, the homos Sovieticus, to the free citizen with creativity and responsibility. It’s easier to make fish soup from the fish than fish from the fish soup.

How was this experience of post-communist reform in economics reflected in the Church? Are there any parallels? And please tell us about hopeful signs, as you have written several books on hope.

The long process — cultural process and moral process — of change was underestimated in our country. And the Church concentrated too much on her own institutional problems. We cannot be alone, Catholics, as the owner of all tools. If we want to teach others, we must also learn much from the others. Only a humble and serving Church is credible.”

I’m so fascinated with this idea of Pope Francis, the Church as a “field hospital,” which could be therapeutic. I think that our world is really ill, and there are many illnesses, including populism and nationalism, national egoism. We live in a very complicated, interconnected global world. We see now the shadow side of globalization — not only globalization of diseases like COVID-19, but also the globalization of fear, fundamentalism, fake news, hatred, violence and political cynicism.

We need global solidarity and compassion. I was so happily surprised by the young people in our country, who were prepared to help other people in the pandemic. I’ve witnessed great solidarity among students and many young people helping others. So this potential of solidarity and sympathy and empathy in the time of crisis has been, for me, a small miracle and a great source of hope.

I enjoyed reading your discussion that the Catholic Church is not an institution that one grabs and holds to oneself. As you are a theologian imbued with strong universal values, please unfold these ideas.

There have always been people fascinated by Catholicism as a closed, unchanging system — as a guarantee of stability in the world, forming the basis of the status quo — “Catholicism without Christianity”; and others who want to change the status quo in the sense of the Gospel.

Since 2000, I’ve discovered people want to go deeper. So we have a program in our academic parish in which we teach people contemplative life within everyday life. This ability to discover God in all things is part of Jesuit spirituality, which is very near to Pope Francis; also, to discern the Spirit in contemplation and to see the signs of the times. I think this culture of personal spiritual life not as an escape into a private “spiritual garden,” but spirituality as a source of activity in the world and solidarity with other people. This is a great program.

And I think we need broad ecumenism now, not just between Catholic and Protestant and Orthodox, but also with other religions and also with seekers of truth. The number of people totally identified with the Church as an institution is decreasing in many places. At the same time, the number of dogmatic atheists is not so high. There are many people who are seekers. And I think we should communicate with them and accompany them with respect. Many “unbelievers” are questioning and are seekers, so we need this new ecumenism with people who are outside the Church and even outside traditional religion. We live in one global village, but to make a real home from this village is a very difficult task. This is what I call a new ecumenism.

We should be liberated from naive optimism, but not fall into pessimism. Have hope, the strength to withstand difficult situations. Our faith should not be the black and white, dogmatic and simple. Our faith must inspire us to seek new answers. Faith is a journey, is a way, and we are on the way, but we are not the owners of the whole truth. The truth is a book, which nobody has read through to the end.

You are a theologian who has drawn from the philosophical tradition of phenomenology, a branch of philosophy that also inspired John Paul II and the Polish movement of Solidarnosc. We don’t have the space to delve into this complex thought, but share with us some of your thinking at the frontier of theology and philosophy, captured in your books published last year by Notre Dame University Press.

Let’s look at what sort of God we believe in. Do we believe in a punishing God who is behind the scenes of our world, who is punishing us through the pandemic, say? I don’t believe in the punishing God, but in a God revealed in the love and solidarity of the people.

Do you think the Church will experience resurrection after the pandemic?

We are witnessing the death of a sort of Christianity. But it is not the final death. I think the resurrection will come, but it will be a surprise. It will be Christ as surprising: Resurrection is not return; it is a radical transformation. Christ met the apostles walking to Emmaus as a foreign pilgrim. And I think sometimes Christ comes to us as a foreigner.

The theology of liberation concentrated on marginalized people, mainly on the socially marginalized people. But there are marginalized people in the churches; they are on the border, looking for a broader horizon. We must communicate with such people, also to learn from them.

When I saw the image of Pope Francis going through the empty St. Peter’s Square in the rain [during the special urbi et orbi blessing on March 27], and I saw in his face all the sorrow and empathy — he’s not an actor; he’s a very authentic personality — I realized how heavy is the cross with the enemies in the Church and gangs and so on. This time of the closed church is also like a warning vision. Perhaps if we do not go through the deep reforms, many churches will be shut down, and they will be closed. Now, in many countries, the churches are empty and closed, and the church buildings and the monasteries and the seminaries are sold. Narrow Catholicism is dangerous.

Pentecost is the moment when people from all nations and cultures were able to understand each other. I think we should look for such a language in our Church today.

To return to your experience under communism, I understand you have written about persecution as being, ironically, something that can benefit Church life.

I spoke about light persecution as being healthy for the Church. If the persecution is too harsh, it can destroy people. But I think light persecution is good; it’s healthy — that if the Church has everything in terms of power and money, it’s dangerous. It spoils us.

I am tempted to ask you if you would consider the 1980s in Czechoslovakia as light persecution as compared to the 1950s.

That was something in between, you know; it was not so light, because it was a special atmosphere. It was not so hard and drastic like in the 1950s. There were no executions. People weren’t sent to prison for 25 years. But the atmosphere of fear regarding the secret police was everywhere. The 1970s and ’80s was a very, very unhealthy atmosphere of collective hypocrisy and moral corruption of the people, which still affects us today. Democracy presupposes a certain cultural and moral biosphere. We must now take care of this in both the East and the West.

Register senior correspondent Victor Gaetan is an award-winning international

correspondent and a contributor to Foreign Affairs magazine.

- Keywords:

- communism

- father tomas halik

- victor gaetan