Will God Wipe Away Every Tear?

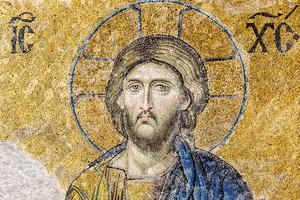

“In his greatness, he has let himself become small. God has taken on a human face.” —Benedict XVI

Does God exist? It is a question that, like death and taxes, never goes away. Indeed, as someone once quipped, God waits in the lobby while the scholars retire upstairs to debate his existence. And, as always, the flash point of their objection is theodicy, which has to do with the effort to acquit God of the charge that he is somehow complicit in the existence of a fallen world.

The usual form of the argument is framed as follows: If God were all-powerful, then he would be in a position to rid the world of wickedness; and if he were all-good, then he would certainly want to do so. But wickedness persists, so either God is not all-powerful, or he is not all-good. In other words, there is no God.

Neat, huh? Can it be refuted? Well, the late Jesuit Father William Lynch, in a profound and seminal work on the literary imagination written back in 1960 called Christ and Apollo, sets out an answer to that argument as it appears in the writings of Albert Camus, perhaps the most prominent novelist and philosopher of postwar France, which is as moving and profound as anything I’ve ever seen.

For Camus, you see, it was simply not possible to believe in a God who seemed powerless to prevent the sufferings of little children. God himself, said Camus, must feel an immense amount of guilt because of so much innocence murdered in his name. He ought to hang his head in shame, as it were, having to witness so much wickedness, yet do nothing to stop it.

Now Fr. Lynch does not deny or dismiss the accuracy of the charge — that, yes, innocent children do suffer and die, and that their cries are surely heard by God, even as they so frequently fall upon a deaf and indifferent world. One would have to be pretty obtuse not to acknowledge the carnage committed against the innocent in the name of religion.

But they do so, he argues, “only within the cries of Christ” (italics added), which are far larger and thus able to contain and encompass an entire world of weeping children. “A man can only cause pain,” he explains, “to somebody outside of himself. But the cries of Christ are wider than we think and grow more actual through the body of our own.”

What a stunning sentence that is! That there could actually be “cries wider than we think,” and that by so expanding their reach they include all the sufferings of the world. How can that be? Is it even possible? What depth and manner of misery must God be willing to endure, in other words, if not even the full weight of the world’s misery can fill him up? A God so majestic that the misery of little children moves him to pity? So powerful that he is able to substitute himself for the least powerful of all?

“In his greatness,” Benedict XVI reminded us, “he has let himself become small. God has taken on a human face.” And with what else could God’s human face be lined save the sorrows of a broken and unjust world? How limitless, then, must the love of God be if it can include the lost cries of little children, whom he gathers up to present to his Father in heaven, who has promised to wipe away every tear!

Each grief the world has known;

the brokenness of every heart.

He made them all his own,

That we may in him find rest.

“He was not like us,” writes Charles Williams, “and yet he became one of us… in the last reaches of that living death to which we are exposed he substituted himself for us. He submitted in our stead to the full results of the Law which is he.”

Why not, then, let God weep and die for us, for at least the life which courses through him is not sundered from ours, even though it may appear to have been sundered from his. Which surely must be so, if the Cry of Abandonment from the Cross means anything at all. “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

Here is the epicenter of our faith, marked by the seeming contradiction of a God at sword’s point with himself; a Father who not only seems to turn his back on the Son, but then seems to send him straight into hell, there to remain in deepest solidarity with all the lost souls of the world. “Let the atheists themselves choose a god,” exults Chesterton. “They will find only one divinity who ever uttered their isolation; only one religion in which God seemed for an instant to be an atheist.”

It was not the Father’s wrath that sent the Son down into hell, and let us hear no more Calvinist nonsense on that score. It was rather out of a sheer incomprehensible depth of love that Christ, the Son, dared to go even there to rescue the least and the lost. If that is not so, then there is no sanction whatsoever for the gospel passage telling us that “he loved them to the last.” It is all a tissue of lies. And there can be no corresponding ascent, either, into Easter joy, since the whole rhythm of his rising from the dead requires that prior descent into the abyss, down into the very bowels of hell. Without which we should be forced to endure a state of forlornness for which no God of love could ever have wished to create us.

- Keywords:

- jesus christ

- suffering

- theodicy