Christ or Caesar? An Election Reflection

When we underestimate the power of Christ, we overestimate the power of Caesar — and Caesar makes a very poor savior.

On a Sunday evening during the summer of 2008 I was walking north on Broadway, toward First Baptist Church. A crowd was circling a scene where a street fair had been taking place. I stopped to see what was going on. A man was lying face down and unconscious on the street. The lenses of his glasses were shattered on the pavement. There were NYPD officers crouched beside him.

Another man, broad-shouldered and wearing a tank-top shirt, was standing near me. His hands were cuffed and he was flanked on both sides by officers. A woman, whom I presumed was the wife or girlfriend of the man in custody, was pleading with the officers, explaining in hysterics that the unconscious man had “been disrespectful.”

“Oh, so that make it okay?” one of the police officers sarcastically asked the woman. “No, but...” and the woman went on to keep explaining in circles that the unconscious man had been disrespectful, to no avail.

Paramedics arrived at the scene. The man who was lying face down regained consciousness. He stood up. Several in the crowd gasped. Blood was running down from the man’s temple to his hip.

A woman, who looked to be in her 60s, was standing next to me. Her mouth dropped wide open at the sight of the battered man. She began speaking her thoughts aloud. “This will stop happening when Barack Obama is the president,” she said.

My thoughts turned to the iconic “Hope” poster of Senator Obama, and to all of the ambiguous talk about “change” during his presidential campaign, all of which had been captivating many millions of my fellow countrymen.

“Once abolish the God and government becomes the God.” —G.K. Chesterton

I do have political leanings. Becoming a conservative while a Muslim in college was, in fact, a stepping stone toward my becoming a Christian later on. One of the fruits of my own Christian journey has been learning that when we identify the most important thing, other matters begin falling into a more proper perspective, that they need not take an emotional toll which they once may have.

Most all people, religious and irreligious, all across the political spectrum, agree that the world has plenty of troubles. Most of us understand that there are limits to what an individual can do about those problems.

What are our troubles? Where do they originate from? Which ones warrant our priority? What ought to be done about them? Who, or what, hinders us from fixing them? Is there anyone who can save us from them? Our answers to these vary, depending upon our worldviews.

Our Christian worldview, insisting upon the grim realism of original sin, insists that only Christ, and the persistence of his Spirit working through us, can rescue our world from the mess we’ve caused. Even our Caesars are in desperate need of Our Lord.

Our Catholic worldview likewise maintains that the Church, having authority to administer the sacraments instituted by Christ himself, shall guide the world until the day of his Return. The Church is greater than any government.

Our Christian worldview does much to protect us from default delusions that any Caesar, using force of law in his rush to “correct” social arrangements, can transform our world into a Heaven on Earth. Nevertheless, this delusion continues to live, despite a historical record of (sometimes catastrophic) failure, that many do fall prey to the belief that an electoral victory for so-and-so spells the salvation or imminent destruction of our nation, that the ballots cast are oftentimes contests between a savior and a devil.

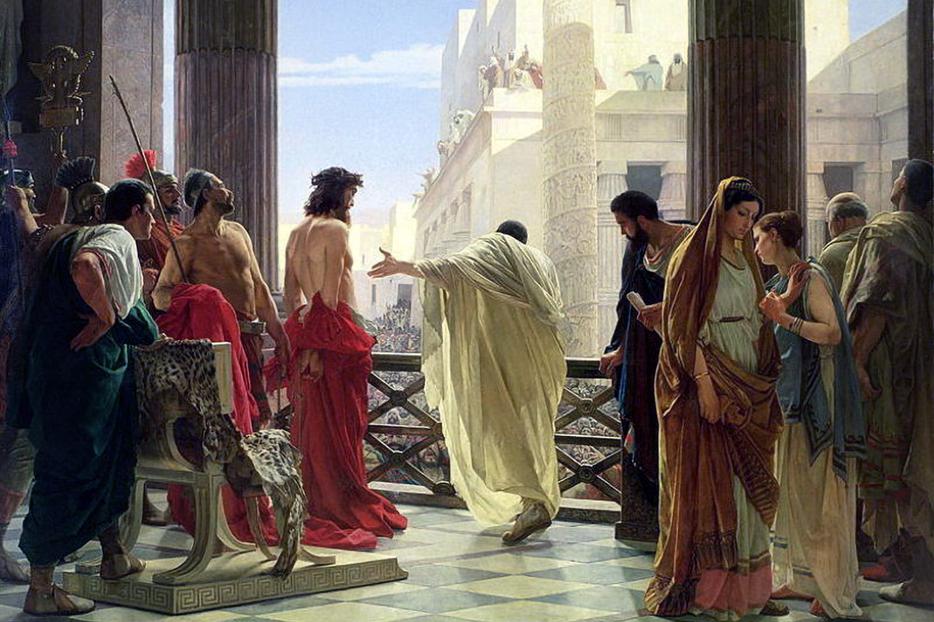

The ancient delusion that kings are supposed to serve as surrogate saviors is chronicled throughout the Old Testament, in many circular efforts to build a “right state” in ancient Israel. It never worked out, with the point being that it cannot work. The New Testament corrects this by insisting that a right state-of-being, driven by the power of the Spirit, must precede any “right state,” armed with the force of law.

Islam, bearing tremendous resemblance to the Old Testament faith, has throughout its history been a catalyst for efforts to build a “right state” to usher an era of godliness and prosperity. Recent infamous efforts to do so have been carried out by the Ayatollah, the Taliban and the Islamic State, among others.

Over the past few centuries, the world has witnessed several large-scale movements, such as Communism (which was atheistic) and the French Revolution (also atheistic), in which a Caesar, having ascended by making utopian pledges, not only failed to bring forth a promised utopia, but butchered millions of men and women in the effort. These ideologically-driven movements, in which humanism turned into something incredibly inhumane, also tended to be overtly hostile toward the Church, as necessity dictated they be. Our Caesars have been at their very worst when given mandates to act as surrogate saviors.

Plenty of those with some libertarian sympathies (though individualism, when not tempered by Church teaching, warrants much criticism) would also gladly point out that, theocratic and totalitarian regimes aside, government-run programs (especially at the federal level), having layers-upon-layers of bureaucratic overhead, tend to be incredibly inefficient at whatever endeavor they set out to do, and that the short-sightedness of such programs routinely yield unintended consequences. Even a visit to the local DMV can be enough to stir wonder in any of us.

Beyond that, our lives are not made or broken by those whom we read about in the news, so much as by those whom we touch. Can the laughter of a child be made any more or less sweet by a person holding office? Is it any more or less fun to share a beer with old friends because of who the president is? Is it any more or less satisfying to say or to hear “I love you” because of an election result? Who in their right mind would answer “yes” to any of these?

Or is it even fair, either to ourselves or to those holding high office, to place such lofty expectations upon a person who is just as fallible as the rest of us?

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” —from the Federalist Papers

Obviously, we’re not all angels. Governments do, of course, have necessary functions. But governments can never be mighty enough to rescue our twisted souls from ourselves. It’s fair to doubt whether those holding office would even be able to make heads or tails out of which among the world’s “problems” are actual problems, meriting of our priority; at least not without guidance from the Church herself.

Whom we elect to office does, of course, matter. It is, of course, a civic duty to vote. History proves that some presidents were more capable of handling crises than others. The pro-life movement would make great strides with the cooperation of government. But when we relativize the Absolute, we become prone to turning secondary matters into absolutes. When we underestimate the power of our Christ, we overestimate the power of our Caesar — and our Caesars make very poor saviors.

The vast majority of us will live out our entire lives without ever having the privilege to meet our president in the Oval Office. And yet every Mass is an invitation to encounter our Christ on the altars of our parish churches, to allow ourselves to be a little more conformed to the Son of God who truly rescues our world, by rescuing us from ourselves. Such accessibility gives us all of the reason to hope, no matter the results of an election.

- Keywords:

- 2020 election

- jesus christ

- christ the king