20th Sunday in Ordinary Time — Setting Fire to the Earth

SCRIPTURES & ART: It is in bearing witness to our faith, in our words as well as our deeds, that Christians divide the world.

We live in an age prone to imagining the Son of God as “good and gentle Jesus” who, unlike actors in our political order, is never “divisive” or “polarizing” but always bent on “unity.” Like the journalist Paul Harvey used to say, “and now, ‘the rest of the story.’”

Today’s Gospel tells the rest of that story. Jesus says he has come “to set fire to the earth,” regretting only “it were already blazing!” Lest anyone pretend otherwise, Jesus says it plainly: “Do you think I have come to establish peace on the earth? No, I tell you but rather division,” even within families, even among the most basic relationships between people, like parent and child.

Jesus came not to establish “peace” but love. Love, however, is not just an emotional “feel good” attitude. There is no love unless, at the same time, it is grounded in truth and objective good. Anything else is not love. It might call itself “love.” It might even sloganeer that “love is love.” But, like the difference between pyrite and the real thing, don’t be taken by “fool’s gold” … or “fool’s ‘love.’” Accept no substitutes! Demand the real thing!

Remember that Jesus spoke the words of today’s Gospel during his three-year long earthly mission. Since then, he has cast fire on the earth. He has set it blazing. It was called “Pentecost” (Acts 2:1-41).

[Before 1969, these Sundays we now call the second part of “Ordinary Time” were called Sundays “after Pentecost” precisely to maintain the linkage to that foundational moment in the life of the Church].

The Holy Spirit did not appear on Pentecost as a “peaceful dove.” He showed himself as fire. He descends on each individual in the Upper Room in “tongues of fire.” He doesn’t come whispering but “like a violent wind” that filled and shook the house.

As a result of that encounter with Divine Fire, the Apostles rushed into the street, speaking in tongues the Truth of Jesus Christ. And, already, the first division followed: Some were “perplexed” but still open to finding out “what does this mean” (which Peter will shortly tell them). Others dismissed them, making fun of them and saying “’they have had too much wine’” (2:12-13).

The Holy Spirit is the source of division. We see that moments after his appearance on the First Pentecost. It’s not that the Holy Spirit wants to divide us, but he is the “Spirit of Truth” (John 16:13) who “will guide you to all truth.” But, in the process of leading you to the truth, he has to get rid of the lies that clutter the path. Some people don’t want to give up those lies. So, if they persist in them, they have chosen division. The Holy Spirit came to bring people to the Truth; he did not come to change Truth to accompany people’s choices. For that, you want another spirit (John 8:44-45).

“Love” without truth is a lie. “Love” without a real good behind it is evil. Because we have stripped “love” of its relationships to truth and good, some people try to counterpose “love” to truth and goodness. They try to pretend that “love” is one thing and morality another. They try to act as if “unity” which papers over essential differences between truth and lies is desirable, as long as it’s peaceful and quiet. So are graves.

There were plenty of times in the Church’s history when it could have had an easier time of things if it just accommodated the times. Lots of people would have been happier over the centuries if the Church focused on Christ and forgot about his Cross. A good part of the Protestant Reformation could have been avoided if the Pope simply winked and nodded at Henry VIII and told him he could divorce his wife and marry another (and another and another and another and another). Lots of moderns would have been happy if Pope St. Paul VI told them they could destroy the life-giving meaning of their sexuality whenever they wanted and practice contraception or sterilization. Nobody would be fighting over Eucharistic incoherence if the Church told people whose positions make them in practice pro-abortion while happening to call themselves “Catholics” that it’s all up to the individual’s “choice” and “conscience.” Even more would be happy if we forgot about the fact that “male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27) is part of what being made in God’s image and likeness involves.

How “loving” the Church would be! Just like the false prophets of the Old Testament, calling lies truth and evil good.

But Christ came to establish Love based on truth and goodness, and that means casting fire on the earth because “the prince of this world [is to be] driven out” (John 12:31). But he will not leave with just an eviction notice. He must be driven out and the wounds he leaves behind cauterized. That is the work of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Fire.

Margaret Turek offers an important insight. God’s love and his anger are not two different things, not opposites. God, who is love, seeks us with passion. He loves us more than we love ourselves. He made us for himself. And when God’s love encounters what is not love, what stands in the way of our being his, of our being “sons in the Son,” his love qua Anger is inflamed to burn that obstacle away. Because he respects our freedom, he cannot do that without our consent, without our willingness to join Christ in atoning for our sins.

But God is God. He is not going to “take us as we are” nor acquiesce in a false notion of our “freedom” that would expect the Holy God to take us in our unholiness, especially if we cling to it. God’s Fire — his Spirit — is purifying. But if it has to burn away what we still want to grasp, that’s gonna hurt. And that’s not God’s fault.

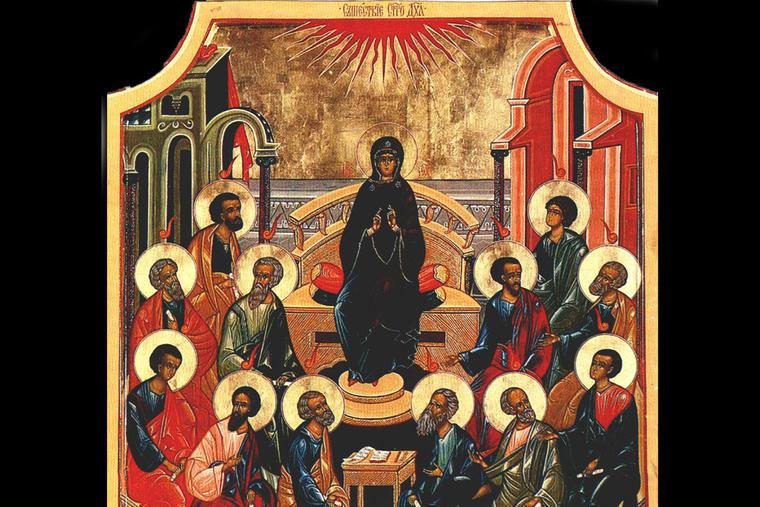

Today’s Gospel is illustrated by a Russian icon, whose date is unclear. It is a Pentecost icon. It depicts the Holy Spirit at the top of the picture as a flame. As in the Acts account of Pentecost, that flame has divided to descend on each of the Apostles and on the Mother of God at the center of the group.

I chose this icon because the flames that appear over each individual are split, “cloven,” so that they actually do resemble a human tongue. It is in bearing witness to our faith, in our words as well as our deeds, that we do divide the world. In bearing witness to the truth, we elicit the pushback of untruth, whether it be those who once believed Jesus was just another creature or those who believe that there is nothing normative about the inviolable sacredness of human life from conception.

Though it is somewhat underplayed in the contemporary Rite of Confirmation, for a long time the Church emphasized that the sacrament exists to bear brave witness to the world in the face of opposition. It’s true that the fundamental charge to bear witness comes from our Baptism, but the Holy Spirit — as we have argued in this essay — is the Spirit who puts each man before Truth, to accept or deny, with all the implications for unity or division that ensue. That’s why a Catholic is not just a Catholic on Sunday: if one’s Catholicism does not guide what he does on Monday through Saturday, there’s something wrong with that “Catholicism.”

After all, even in the prayer that invokes the “good and gentle Jesus” does so in the light of the cross and its consequences. That’s why it was traditionally called “A Prayer before the Crucifix.”

Jeremiah in today’s First Reading bears witness to this same dilemma. Jeremiah was a true prophet amidst a gaggle of false ones. Judah, the southern Kingdom around Jerusalem, was on the verge of destruction. Its king, Zedekiah, waffled about listening to Jeremiah, more inclined to rely on the “Realpolitik” of his “advisors” who flattered him into thinking his little kingdom could play big politics on the stage of the ancient Near East. Eventually, the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem and deported its inhabitants, including Zedekiah, to Babylon, where the Judean king’s sons were promptly slaughtered and Zedekiah’s own eyes blinded.

Jeremiah suffered for his fidelity to the truth, for this calling on Zedekiah to stop playing politician and start playing King of Judea, leading his people to repentance and turning to God. For this, he suffered numerous attacks, including being thrown into a cistern, i.e., a dried up well, where he was constantly in danger of sinking into the mud left at the bottom and suffocating to death.

Our second piece of art today is Marc Chagall’s etching, “Jeremiah Thrown into Prison by King Zedekiah’s People.” Jeremiah is shown bound, but he is interiorly free in the light of God’s grace shining upon him. A guardian angel hovers on the right (“he will command his angels to keep you in all your ways – Psalm 91:11). Recognizing he is not in control and only God can save him, Jeremiah bows his head.

Chagall was a 20th-century French-Jewish artist who came from what is today Belarus. His artistic styles incorporate two major elements: a blend of modern Western approaches to art together with a traditional Jewish style and piety. He was one of Pope St. Paul VI’s favorite modern artists.

- Keywords:

- scriptures & art

- unity