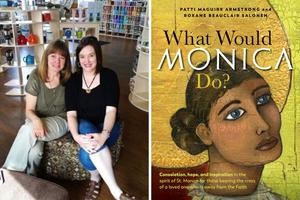

‘Tears of the Heart’: The Story Behind the Cover Art of a New Book on St. Monica

‘It’s always been about the tears.’ — Jill Metz, sacred artist

When sacred, mixed-media artist Jill Metz started her depiction of St. Monica, she didn’t know it would someday grace the cover of a book or be named, Tears of the Heart.

The naming didn’t happen until Ascension Press contacted Metz earlier this year, requesting use of the image for What Would Monica Do?, the new book I co-wrote with Patti Armstrong addressing the heartache of loved ones who have left the faith.

Since the piece had yet to be named, Metz did what she always does in approaching her art. “I prayed, asking St. Monica to help,” she said. “I think I’m pretty docile to the will of God, and when I prayed, it was really about the tears. It’s always been about the tears.”

In fact, after she had completed and even varnished the piece, she sensed God directing her to “go back and add a tear.” It was raised from the rest of the image and not discernable on the book-cover rendition. But Metz knows it’s there — just like Our Lord knows the intricacies of all hearts.

“The enemy wants us to believe this world should be filled with no tears,” she added, “but we see that’s not so through the work of the cross.”

Ascent to God

Metz grew up in a home of addiction and divorce. Without any foundational faith, she dipped into the occult, exploring tarot cards and astrology. “The enemy was always there, tempting me,” she recalled, and like St. Augustine’s, her heart was restless.

At 17, Metz felt a prompting and stopped at a small country church. “I went in and just poured out my heart to the Lord, singing (Amazing Grace) at the top of my lungs,” she recounted. “I think God marked me at that moment, and I really started pursuing religion.”

Metz eventually met and married her husband, Ken, a cradle Catholic, and readily agreed to raise their children Catholic. “That glance toward God had happened. I opened the door, and he came,” causing a yearning to be part of something bigger, she explained. But she wasn’t interested in Catholicism for herself.

“If I ever do become a saint, I would be the patron saint of stubbornness,” she admitted. Despite attending Mass with Ken, she did not believe in the Real Presence. “I just didn’t see that that could possibly be real from the way [people] were receiving and dressing. There was no witness that there was something different here.”

But in 2009, experiencing a time of spiritual aridity, Metz began “yearning for the comfort he had always given me.” God was indicating to her it was time to enter the Church, but in hearing this call, she said, “I slammed my fists down on the kitchen counter and said, ‘Anything but that!’”

She challenged God, saying that if he really wanted her in the Church, he would have to make it abundantly clear. That night, she went to tuck in her son, who was preparing for his first Communion.

“Only a mother can understand the way that a child seeks and speaks,” she said, noting that, when she threw back the covers, she saw him clutching a plastic rosary with heart-shaped beads. “His little hand went up, and he threw it at me, saying, ‘Here, Mom, I want you to have this.’”

That was all it took. “It was God using the lowliest one to strike down the strong,” she said. “I knew in that moment that, yes, I was being called into the Catholic Church.”

Her ascent helped inspire her husband’s reversion, and soon after her reception into the Church, she was coordinating then-called Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) at her parish.

Finding Sacred Art

Metz chose Elizabeth Ann Seton as her confirmation saint, noting that the saint had once uttered that if people knew the Real Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, they would be crawling on their hands and knees to receive him.

“This was all grace,” she said, noting that the priest who formed her was very Eucharistic, and she would spend every Friday in a Holy Hour with him. “He was a good teacher of the faith, and God sent me what I needed at the time.”

Metz consecrated herself to Mary and her children to the Blessed Mother, as well. “I had my conversion, and then our Blessed Mother chose me,” she said. “After that, I really did experience quite a miraculous freedom and liberty that I no longer had to be concerned with the welfare of my kids.”

They were young at the time, 9 and 10, she added, “so I had not experienced yet a lot of the worldly issues our young people face.”

Metz was enjoying her work as a mixed-media artist. When a friend requested she paint a saint for a Catholic-radio fundraiser, after some hesitation, she relented, ultimately producing a depiction of St. Lucy.

Soon thereafter, Metz discovered a dark blob in one of her eyes, causing partial blindness and requiring medical intervention. A friend suggested she pray to St. Lucy, and when, just days later, the blob disappeared, Metz was powerfully awakened to the intercession of saints.

Before the blob dissolved completely, however, it changed into the shape of a heart, Metz said. “Ever since then, I’ve done nothing [artistically] but paint the saints.”

Meeting St. Monica

For each work, she appeals to God and seeks to know the saints through their intercession.

“With St. Lucy healing my eye, I was all-in with what they were there for: to teach and guide us,” she said. To create the right prayerful atmosphere as she paints, Metz incorporates sacramentals, “everything from having relics around me to using holy water. I also have an exorcised candle burning. I really try to create a sacred environment and enter into that.”

She also invites the Holy Spirit to join her. “It has really taught me to trust the Lord. I’ve learned how to distinguish God’s voice from other voices. It’s a great gift that I cannot take any credit for, to be honest.”

Metz did not know a lot about St. Monica as she set about praying, but she felt her presence and “a real love” as she asked her intercession. “We know these saints choose us,” she said, noting that she also was inspired to make her eyes blue. “I wanted her eyes reflective of being sorrowful. For whatever reason, blue represented to me the color of sorrow.”

In St. Monica, Metz sees “persevering in our suffering, our disappointments, and hoping for the goodness of the Lord. I’m still in awe of her. I just think she’s a powerful saint for this time, as so many of our kids are so lost.”

Ultimately, Metz returns to the most divine element of her Monica art: the tear. “That’s what I would hope women especially would see [in this image]; to never deprive the Lord of your tears, your dreams, your wants — and to know how he delights in giving you an answer in those tears.”

LEARN MORE

Find more of Metz’s work at her website, TruOriginal.com.