Freud’s Last Psychoanalysis With C.S. Lewis?

New movie imagines an intriguing possibility.

HOLLYWOOD — C.S. Lewis is back on movie screens this winter.

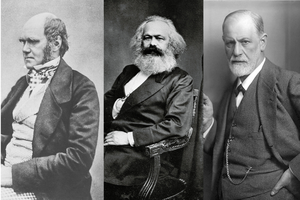

Released this Christmas, Freud’s Last Session stars Anthony Hopkins as Sigmund Freud and Matthew Goode as Lewis.

The movie is set on the eve of the Second World War. Having fled the Nazi takeover in Austria, Freud has ended up in London. It is there, in his Hampstead house, that he meets the Oxford academic Lewis, who, a few years earlier, has converted from atheism to Christianity. The purpose of Lewis’ visit to the dying “Father of Psychoanalysis” is to debate the relationship between science and religion, faith and logic, and how the intellect may help, or hinder, the soul’s path to belief in God. Including fantasy sequences, the movie frames this existential debate between the two men in and through their past experiences and present reality.

Of course, the film is pure fiction; there is no record that the two men ever met.

The film’s genesis may be traced to 1967, when Dr Armond M. Nicholi Jr., clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, gave a series of lectures at Harvard University called: “The Question of God.” They explored Freud’s atheistic theories but included discussion of aspects of Lewis’ Christian writings. Subsequently, in 2003, Nicholi published the lectures as: The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of Life.

The film’s co-writer, Mark St. Germain, used that book and its thesis as the basis for his 2009 stage play: Freud’s Last Session. Based on the stage play, the screenplay of the new movie is co-written by St. Germain and the film’s director, Matthew Brown.

Brown, whose last movie was The Man Who Knew Infinity (2015), for which he was writer-director, spoke to the Register from Hollywood on Dec. 18.

Why did he make this movie? “Tried not to make it for a while!” Brown says as he laughs; he then explains how, coming across St. Germain’s play six years ago, he was immediately struck by its premise, especially in relation to the times in which we live.

“The play’s theme spoke to what was going on in the world then — so may parallels: loudest voice in the room taking over society; media and everything; and fascism seeming like not something improbable.” He senses that in the intervening years since coming across the play there is an even more pressing need to examine these themes. “Right now,” he maintains, “this film could not be more timely to start a conversation” around the subjects debated by its two protagonists.

“We live in a strange, surreal age that is ideologically polarized, with everyone stuck in their own tribes,” observes Brown. “There’s no respect for others’ points of view — and yet a real dialogue with others is exactly what people seem to be thirsting for. In the film, we have these two titans with diametrically opposed points of view who choose to respectfully battle out their differences over God.”

Is this a film, therefore, essentially about the clash of two worldviews — one religious and one secular? To some extent, Brown agrees. But, intriguingly, he posits the movie as the cinematic equivalent of a “therapy session for both men.” He hopes that the movie has “more depth” than simply featuring a heavyweight intellectual joust between Freud and Lewis.

“I knew the film needed to be cinematic and delve fully into the ‘dream aspect’ of this fictional meeting, exploring the subconscious of these two creative minds, who challenged society’s norms,” says Brown. “Whether through Lewis’ fantasy world or the Gothic forests and erotic hallucinations of Freud’s subconscious, the imagery and filmic landscapes would need to escape the confines of Freud’s home, where the dramatic discussion takes place.”

Set on the brink of a world war, Brown feels this gives the film “a very real sense of urgency; their personal stakes reflect the weight of the impending war, and what’s going on between these two is critical for all of us in some way.”

The film also portrays both men prior to their meeting and to their rise to prominence. The First World War experiences of Lewis are explored, as well as his subsequent romantic dalliance with Janie Moore, the mother of a fellow soldier with whom Lewis had fought in the trenches. The Oxford-based writers’ group The Inklings (which included J.R.R. Tolkien) also makes an appearance. On Freud’s side, the film predictably delves into the world of sexual impulse, whether conscious or subconscious. Freud’s daughter Anna Freud, who also would become a psychoanalyst, features prominently, as does her girlfriend.

The two-time Oscar winner Anthony Hopkins previously played Lewis in the 1993 film Shadowlands. This time, he plays Freud opposite Matthew Goode as Lewis. The advice on the part of Lewis from Hopkins to Goode was, says Brown, “I created my Lewis; you create your Lewis.”

Of the two lead actors, the director sensed a “real respect there between the two of them. … Tony [Hopkins] did a tremendous amount of preparation to play Freud, and Matthew [Goode] really delved into the character of C.S. Lewis. … As a filmmaker, I really learned how to make space for the actors to grow on this film, and it was just an incredible experience because they were all so committed.”

Brown is the son of a psychiatrist, so was he acquainted with Freud and his work prior to becoming involved in the movie? “Definitely a name in the house!” he replies. But then he admits that through working on the screenplay and recent discussions with his father, he came to know the psychoanalyst in a different light. “In talking to my father, I came to a different understanding of Freud. I realized how intellectually curious Freud was and how he challenged his own beliefs. … I feel if Freud had continued on till today, he would have laughed at some of his theories.”

And what, if anything, did he know of Lewis prior to this project? “I grew up a huge fan of the Narnia books, but I did not know the Christian themes within them,” Brown explains. That said, he was aware of The Inklings and the university world in which Lewis lived and worked, even though he was not fully versed in the writer’s back story, particularly his journey from atheism to Christianity and the influence of Tolkien and others in that journey.

Brown feels that the movie attempts to unravel the “deeper layers to Lewis and Freud” than is sometimes recognized. His film seeks, he suggests, “to peel those layers back a little bit for the audience.”

“The beauty of the story,” he continues, “is that while there are no answers, it’s only through conversation that personal growth becomes possible for each of them. I wanted to make a film that was emotional, thought-provoking and creative, that asked big questions, and looked deeply at the heart of the human condition: love, faith and mortality.”

Ultimately, Freud’s Last Session explores whether two of the most renowned 20th-century intellects, notwithstanding their differences, could find “connection.”

Does Brown think true connection would have been possible for these two men, given their contrary worldviews?

“It is always a process of discovery making a film, and as I was watching it on screen, it really became clear to me that Freud doesn’t want Lewis to leave the room, and Lewis doesn’t want to leave either. They have had an intellectually curious, respectful, heated at times, debate, but they like each other.”

WATCH

Freud’s Last Session opens Dec. 22 in New York City and Los Angeles. Viewer Caveat: Rated PG-13, for thematic material, some bloody/violent images, sexual material and smoking.

- Keywords:

- freud

- cs lewis

- catholic movies

- anthony hopkins

- matthew goode

- catholic psychotherapy association

- psychology

- catholic conversions

- atheist conversion