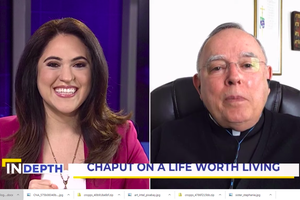

Archbishop Chaput’s New Book Addresses Man’s Greatest Spiritual Poverty: Not Knowing How to Die

REGISTER BOOK PICK: If we do not have a clear idea of our final end, then we will not know how to begin living.

Things Worth Dying For: Thoughts on a Life Worth Living

By Charles J. Chaput

Henry Holt, 2021

272 pages, 25.99

“On your walls, Jerusalem, I have set my watchmen to guard you” (Isaiah 62:6).

For decades Archbishop Charles Chaput served as a strong prophetic voice for the Church in the United States. He was that watchman on the walls of Jerusalem — discerning and proclaiming the truth for God’s people. Although retired now for over a year, he still continues that good work. His important new book, Things Worth Dying For: Thoughts on a Life Worth Living, is the voice of the watchman. It is an extended reflection on where we come from, where we are now, and where we should want to go if life is to have meaning.

Early on in the book the archbishop uses the phrase “memories of things worth dying for.” It is a curious expression to the modern mind. Memory and death don’t mean much to us. We don’t have much use for the past and we try to cheat death constantly. It is hard to think of a culture more disconnected from its own past and more fearful of death.

Nevertheless, these two things — memory and death — form and frame the archbishop-emeritus’s book. Of course, it is tempting to see them as the predictable topics for a man in retirement, facing his exit from the stage. Perhaps they are. But that doesn’t make them any less important. And we ought to heed the wisdom of such men. For the memory here is not mere nostalgia, and the dying not mere death. They are, rather, the memory and the dying that give meaning to life.

One of our culture’s most conspicuous vices is impiety — that scorn and dismissal of one’s own patrimony. It is a willed amnesia, a deliberate forgetfulness. It is the rejection of the past that has made us who we are. It therefore cripples our ability to know ourselves. Against this forgetfulness Israel’s prophets always called out, “Remember!” So now the archbishop warns against the destruction of the past that has such grave effects in the present and for the future.

His reflections on memory shed light on our current situation. Archbishop Chaput observes that “the most telling feature of our era is that it weakens bonds.” That weakening begins with the forgetfulness of where we came from and therefore of who we are. By weakening our bonds with the past, the agents of impiety more easily weaken our bonds in the present.

The consideration of those bonds — with God, country, family, the Church — occupies the majority of the book. In each chapter Archbishop Chaput addresses a particular bond. He provides an analysis of how we got here and a prescription for how to get out. What’s always striking about the archbishop’s writing is that he diagnoses our societal, political, and ecclesial ills without scolding and prescribes strong medicine without moralizing.

Then there’s that other theme. The archbishop dedicates two entire chapters — one at the beginning, another at the end — to the topic of death. Or, more accurately, on how to die. “In my end is my beginning,” T.S. Eliot writes. If we do not have a clear idea of our final end, then we will not know how to begin living. If we don’t know how to die, then we don’t know how to live.

Thus a culture’s approach to death determines and reveals its way of living. And one of our culture’s great impieties is the trivialization of death. Funerals are simply something to get done so that people can move on. The body is disposed of unceremoniously, as just another piece of refuse.

Unfortunately, even within the Church, as any parish priest can tell you, our approach to death is superficial. Insipid hymnody and auto-canonizations seek to take the sting out of the inevitable.

As a culture we are whistling past the graveyard, hoping that by domesticating death we can avoid the demands it makes on the living. And yet, as Archbishop Chaput observes, “Denying [death], refusing to face it, or draining it of its meaning steals something profoundly human from life.” We think that we have cheated death when in fact we’ve only robbed ourselves of meaning. “Too often today, many of us do not know how to die. The sacred sense of passage our culture once attached to death no longer exists, but our fear and anxiety have never been stronger.”

Some years ago, a Missionary of Charity, one of Mother Teresa’s closest advisers, looked firmly and serenely at a visiting priest and said, “Father, we prepare people for death.” Now, that phrase won’t make a popular mission or “vision” statement for a parish or diocese. But it gets to the Church’s purpose pretty quickly. Her teachings and sacrament address man’s greatest spiritual poverty: not knowing how to die.

So Archbishop Chaput writes of “The King’s Highway,” the pathway to heaven trod first by Our Lord and now by his disciples. Indeed, followers of Christ should be — as we once were — beacons in society to chart the proper course through death to eternal life. Thus the Church would give to the world the proper assessment of its worth.

In reflecting on the King’s Highway, the archbishop provides a wonderful consideration of the four last things: death, judgment, heaven, and hell. But most importantly, he explains the truth that The King’s Highway has a destination and purpose, an end that determines its beginning and every step: heaven itself, “the worthiest goal to live and die for.”

These two themes — memory and death — are intrinsically united. If we do not know the past, neither can we understand the present or prepare for the future — and least of all for the ultimate future of death. Those who have gone before us have given us an inheritance of wisdom that prepares us for the journey through the life.

As Archbishop Chaput makes clear throughout the book, if we refuse to receive that wisdom — that is, to remember — and insist on creating our own new meaning, then we will no longer have things worth dying for. And thus nothing worth living for.

It is the watchman’s duty to remember for us. Archbishop Chaput has shown himself once again to be a faithful pastor, bringing to our memory those truths worth dying for.