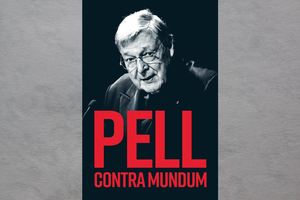

‘I Am Caught in the Struggle Between Good and Evil’: Cardinal George Pell’s Prison Journal Is an Engaging Read

BOOK PICK: Vol. 1 details the Australian cardinal’s daily log entries from the first five months of incarceration.

The Cardinal Makes His Appeal

By Cardinal George Pell

Ignatius Press, 2020

348 pages, $19.95

To order: ignatius.com or (800) 651-1531

Days after Cardinal George Pell began his six-year prison sentence in February 2019, after a jury found him guilty of sexually abusing two minors in 1996, he picked up his breviary and pondered the week’s eerily appropriate readings from the Book of Job.

Job’s “troubles are just beginning. It all lies ahead for him,” the author muses in The Cardinal Makes His Appeal, Vol. 1 of his Prison Journal that covers the first five months of his incarceration, Feb. 27 to July 13, 2019.

Cardinal Pell knows how Job’s story ends, and so “takes some consolation from” the trials of the Old Testament figure. “[H]is good fortune was restored in this life, unlike the good Lord’s, and I still believe that the only just verdict for the judges is to quash the convictions,” says the cardinal, referring to hopes that his own guilty verdict will be overturned following his upcoming appeal.

Job’s story traces one man’s struggle to understand the problem of human suffering, especially when the pain is inflicted on a just man. And Cardinal Pell’s engaging journal touches on this mystery and the Church’s response, while celebrating the healing power of Christian faith and fellowship during desperate times.

“We Christians believe suffering in faith can be redemptive, that salvation was gained for us by Christ’s suffering and death, and that the worst can be redeemed,” he writes. “Job did not have Christ as his model in his suffering.”

But there is a difference between Catholic doctrine and personal experience, as the author himself acknowledges.

“For those like myself who have led sheltered lives, never being caught up in war or terrorist attacks, etc., we can be inclined to underestimate the evil in society and the damage done to many people, victims.”

With the first installment of the journal published just weeks after the Vatican’s Nov. 10 release of the McCarrick Report, the cardinal’s reflections will surely prompt readers to confront the paradox of a Church that contains within its ranks both shepherds who are wrongfully convicted of abuse and predators who escape punishment, prelates who root out corruption and those who fuel it.

Cardinal Pell, for his part, does not know how his own story will end as he writes, and that fact makes his daily journal entries all the more striking. In fact, the former archbishop of Sydney and prefect for the Secretariat of the Economy will serve 409 days in solitary confinement for his alleged crime.

His first appeal results in his conviction being upheld. But a second appeal leads the Australian High Court to unanimously rule in April that he was wrongly convicted on evidence that “did not establish” the “requisite standard of proof” of guilt.

So to be clear, the first installment of his prison journal deals with his legal case in a limited way, mostly to show that the cardinal has begun to consider fresh explanations for the complainant’s decision to accuse him of a heinous crime he has not committed. He expresses no animus for the alleged victim and has forgiven him.

Further, the cardinal does not address recent, unsubstantiated accusations that suggest corrupt Curial officials, who sought to block his financial audit of their offices at the Vatican, may have played a role in the allegations that forced the cardinal to leave Rome voluntarily to return to Australia to clear his name.

The most compelling aspect of this journal is the way the author approaches his new life in prison and how this experience reveals the impact of the Refiner’s fire on a man of deep faith who is also tough, intelligent and accustomed to wielding power: “I was overdue for a retreat,” he observes at the beginning of his journal.

After more than four decades as a priest and two as a bishop, the new prisoner, the highest-ranking Church leader to be convicted of the sexual abuse of minors, knows he must establish a plan of life anchored in prayer and scriptural reflection.

“God our Father, help me to yearn for you, just as I yearn for the light and sight of the sun,” he writes at the close of one of his first entries.

Slowly, he adjusts to the indignities and deprivations built into the daily routine. Foremost among them is the fact that he will be unable to attend or celebrate Sunday Mass for the first time in “more than 70 years.”

Chaplains who minister to the incarcerated know that prison can become a monastery. And the author’s cell is like a monk’s — small, rough and cramped, with a toilet, bed and desk in close proximity. Weekly housekeeping duties include sweeping and mopping the cement floor. Other prison rituals take longer to shrug off, like the strip searches that precede meetings with visitors.

Some of his time is occupied with ongoing analysis of the legal case for his appeal, correspondence with fellow prisoners and friends, and regular, if limited, exercise.

But at times, this former Aussie Rulees Football player finds the anxiety and strain associated with his uncertain fate hard to overcome. There are few distractions to be found in the silence of Unit 8 at the Melbourne Assessment Prison where inmates condemned to solitary confinement are confined. The 12 prisoners in the unit never meet each other, but some register their presence by howling or banging. One inmate corresponds regularly with the cardinal who describes him as a “friend.”

Once an influential force in Australian life, the Church leader finds himself looking forward to the visits of the prison chaplain, a woman religious, who brings him the Eucharist and the precious gift of fellowship. The author’s preference is to show, rather than explain, the spiritual impact of these interactions, making his testament all the more powerful.

In the most moving passages of the first volume of his journal, the cardinal’s spirits are buoyed by the countless letters of support and instruction he receives from well-wishers across the globe, many of them Catholics who believe he is being persecuted for his faith.

“[T]hese letters have changed my time in jail, my daily program, my thinking and praying, my peace of mind,” he writes.

During daily prayer and reading, he also finds inspiration in the example of the saints, especially the martyrdom of Sts. Thomas More and John Fisher, and believes he has been targeted because of his faith and prominence as a Catholic leader.

“I am caught in the struggle between good and evil,” he concludes at one point.

The first installment of his prison journal, however, does not address the great evil of clergy sexual abuse with the kind of depth, honesty and passion that some readers may have hoped for.

While the cardinal, who will turn 80 next June, has been accused by some Australian victims’ advocates of both failing to respond quickly to early reports of abusive priests and of blocking initiatives to obtain more compensation from the Church, specific passages in the journal generally defend the Australian bishops’ efforts to correct their past mistakes: “[T]he evidence is that the worst of the institutional wrongdoing in the Catholic community was radically curtailed, where it was not eliminated, over twenty years ago.”

Still, he acknowledges the enormous challenges that historic abuse allegations have posed to Church leaders like him.

“In my not completely limited experience, the pedophilia crisis is the most vexed area I have encountered, where it is often difficult to identify the truth,” he writes. “Neither do I know of any other area of life with an equal capacity to warp and damage individual judgment, whether the persons are good, bad, or indifferent.”

He notes that he prays “explicitly each day for the victims.” And, more recently, he has begun praying regularly “for offending priests and delinquent bishops,” including “Ted McCarrick.”

In a striking understatement that may disturb U.S. Catholics in particular, the cardinal remarks that McCarrick “caused a lot of harm in more ways than one.”

Some readers will take this comment as evidence of the author’s failure to understand the gravity of crimes committed by McCarrick and others like him. And yet Cardinal Pell’s prison journal reminds us that an innocent man was wrongly convicted of a crime and that he responded to this injustice not only by mounting an appeal, but by bringing his sufferings to Jesus.

The cross is where the Lord, who “accomplished the substitution of the suffering Servant,” makes “himself an offering for sin,” states the Catechism of the Catholic Church (615).

Cardinal Pell’s story reveals that God gives each of his disciples work that he has not committed to another. And in the author’s case, readers will be moved by his sufferings and see them as an offering for the sins of his fellow cardinals who will not pay for their crimes in this life.