Former Slave’s Remains Exhumed, Laid to Rest at Denver Cathedral

Servant of God Julia Greeley is first person entombed at archdiocese’s mother church.

DENVER — She was a laywoman, a Catholic convert, an ex-slave — and she is the first person to be buried at Denver’s 105-year-old cathedral.

The remains of Servant of God Julia Greeley were recently exhumed from a local cemetery. And on June 7, the 99th anniversary of her death, they were transferred to the Cathedral-Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, where people lined up for the unique opportunity to view and venerate her earthly remains before they were entombed.

The ritual is part of the investigation process for Greeley, whose cause for canonization was opened in December. One of six African-Americans being considered for sainthood, Greeley is the first person the Denver Archdiocese has proposed for canonization.

“She will be the first person buried in Denver’s cathedral,” Auxiliary Bishop Jorge Rodriguez told the congregation. Drawing applause, he emphasized, “Not a bishop, not a priest — a laywoman and former slave. Isn’t that something?”

Born as a slave between 1833 and 1848 in Hannibal, Missouri, Greeley arrived in Colorado in 1874, 11 years after slaves were freed. Four years later, she came to Denver with Julia Gilpin, wife of Colorado’s first territorial governor, William Gilpin. Following her conversion to Catholicism in 1880 at Sacred Heart Church in Denver, she became a daily Mass attendee.

After leaving the Gilpins’ service, Greeley did odd jobs cooking, cleaning and caring for children. Despite her scant means, she became known as Denver’s “Angel of Charity,” as she went through town pulling a red wagon filled with items she bought, found or begged for poor families and which she often delivered at night in secret.

Known for her devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, each month she walked to all 20 of Denver’s fire stations to give Sacred Heart prayer pamphlets to firefighters because their jobs were so dangerous. She died on the feast of the Sacred Heart, after falling ill on her way to morning Mass. She was 70-85 years old.

At the liturgy for the transfer of her remains, Bishop Rodriguez highlighted Greeley’s heroic humility, perseverance and faith.

“We know from the stories passed down to us that Julia Greeley was tireless in her charity and in spreading the faith,” he said, adding that the exhumation revealed she suffered from arthritis in her hands, feet and back.

“Almost every joint that could have hurt, probably did,” he said. “Nevertheless, she never stopped practicing and doing and showing love.”

Forensic anthropologist Christine Pink of Metropolitan State University, who supervised the exhumation, confirmed Greeley’s arthritis.

“Given the persistence she had, every day walking the streets of Denver and spreading the word, I think it would have been quite painful for her just to move,” Pink told the Register.

In addition, as a child, Greeley lost an eye to a whip while she clung to her mother who was being beaten by a slave-master.

The Church’s canonization process exhumes bodies to verify the person’s identity, to prove he or she existed and to check the condition of the remains, explained Bishop Rodriguez.

“The body is handled with reverence; it is given special care because that person was baptized, anointed and has been made sacred,” he said. “Those bones are destined for resurrection.

“We believe in the resurrection of the body and in the communion of saints.”

When she died, she was so beloved that her body lay in state at a small chapel for five hours, as a constant stream of people from all walks of life paid their respects to her.

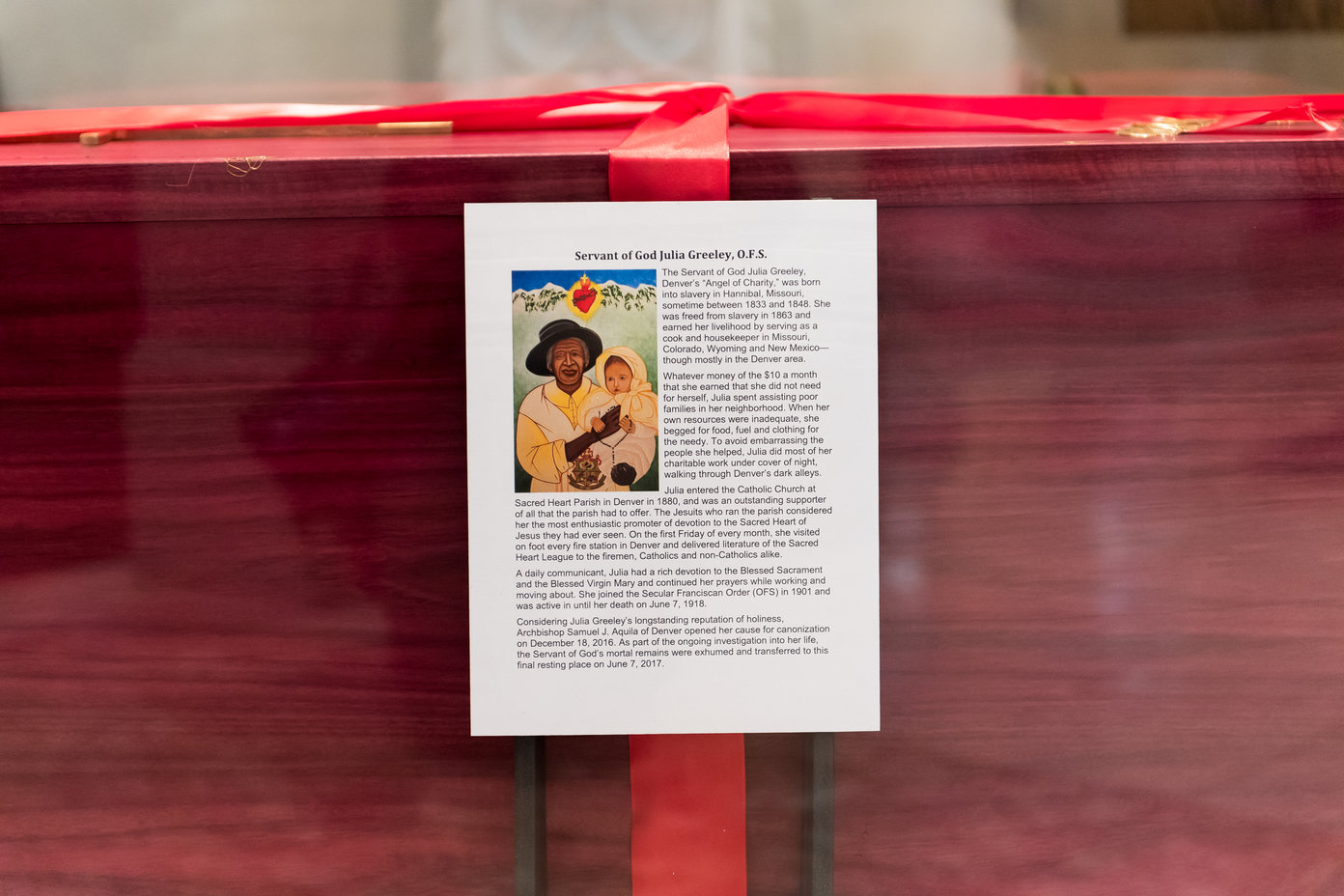

At the cathedral-basilica liturgy, people peered through glass covering the wooden funerary box holding her skull and bones and touched rosaries and other items to it before the box was screwed shut and sealed with ribbon and wax.

“With all the people coming up, it occurred to me that’s what happened the first time in the little chapel on Ogden Street when people passed her coffin,” Capuchin Franciscan Father Blaine Burkey, author of a comprehensive biography on Greeley titled, In Secret Service of the Sacred Heart: The Life and Virtues of Julia Greeley, told the Register.

“I was touched by the fact there were so many people — and so many children,” he said. “She loved children. This isn’t the normal thing you’d expect children to go to.”

The only known photo of Greeley, taken two years before she died, shows her holding an infant girl she occasionally helped care for named Marjorie Ann Urquhart.

The Denver liturgy included the blessing and censing of the remains and of the funerary box, the creation and blessing of third-class relics — a brown habit like the one Greeley wore as a secular Franciscan was touched to her remains — and the reading and signing of decrees testifying that Church protocols had been fulfilled.

After veneration, the funerary box, which also contained dirt from her original grave at Mount Olivet Cemetery, what was left of her original coffin, and certificates authenticating the bones as Greeley’s, was placed beneath a statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the West transept of the cathedral-basilica and covered with Plexiglas.

A marble sarcophagus is being made to enclose the funerary box; expected to be done in six to eight months, it will serve as Greeley’s permanent tomb.

“On this day, we reach the culmination of a process approved by the Holy See to bring her mortal remains to this holy place, where the faithful may venerate her privately, yet fittingly and appropriately, this great daughter of our archdiocese,” Bishop Rodriguez prayed during the liturgy.

Archbishop Samuel Aquila tweeted about the momentous occasion: Transferred remains of #ServantofGod #JuliaGreeley to final resting place @ Cathedral of Immaculate Conception. Julia, pray for us! +sja

When the diocesan phase of the investigation closes, the investigators will send a report to the Vatican with their findings. The Congregation for the Causes of Saints will then vote on whether the cause will continue. If affirmed, the Pope can recognize the person’s heroic virtue and deem her “Venerable.”

Two miracles are then needed — as evidence of the person’s intercessory power and thus of union with God — before the person can be canonized.

“We’ve just seen … since December, when her cause opened, just how authentic the devotion of people to Julia Greeley is,” David Uebbing, chancellor for the archdiocese and vice postulator for Greeley’s cause, told the Register. “It’s good to hear of even small things, like, ‘I prayed to Julia to make my headache go away, and it did.’

“To see that intercessory power, you feel like she’s a part of your family and of the communion of believers,” he said.

Mary Leisring, head of the Julia Greeley Guild (JuliaGreeley.org), which exists to build awareness of Greeley’s sanctity, told the Register she hopes people will ask Greeley’s intercession and will let the guild know in writing of answered prayers.

“Here’s a lady who exemplified what holiness is,” she said. “I’m not sure that if I’d experienced what she had I’d be able to be holy. It reminded me to call on Christ for everything. If we do that, we can become extraordinary, too.”

“Whether she becomes a saint for Rome or not,” Leisring asserted, “she’s already my saint.”

Roxanne King writes from Denver.