Saving the Shrine of the North American Martyrs

A national place of pilgrimage closed for lack of Jesuit priests is experiencing the start of a new era, thanks to a joint Catholic effort.

AURIESVILLE, N.Y. — Newly ordained a priest, Father Francis Vivacqua decided to celebrate his Mass of thanksgiving at the place where he always enjoyed coming as a boy: the shrine to the North American Martyrs in the Mohawk River Valley.

In the coliseum church of Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine, the priest stretched out his arms before the altar, chanting the Mass that his hero, St. Isaac Jogues, prayed nearly 400 years ago among the Mohawk Indians, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, also known as the Haudenosaunee.

Several hundred people gathered at the shrine on Father’s Day 2016 to give thanks to the Heavenly Father for his blessings: Father Vivacqua thanked God for his priesthood; Jacob Finkbonner carried up the priest’s chalice to thank God for the miracle he worked by St. Kateri Tekakwitha’s intercession 10 years ago, saving the 15-year-old’s life from a rare flesh-eating disease that attacked his face; the congregation thanked God for this new priest, the miracle that saved a boy and convinced the Vatican to declare the “Lily of the Mohawks” a saint, and divine assistance in saving the sacraments from disappearing at Auriesville.

As Father Vivacqua held his arms outstretched in prayer on behalf of himself and the whole congregation, he became aware that his fingers were no longer stretched straight out. Two of his fingers, he noticed, had closed in toward his palm. Immediately, he recalled how his hero, St. Isaac Jogues, had lost those fingers because his Mohawk torturers gnawed them off with their teeth, knowing that a priest with mutilated fingers — under the Church’s rules at the time — could not offer the Mass. But Pope Urban VII intervened, saying, “It would be unjust that a martyr for Christ should not drink of the blood of Christ.”

So there upon the Auriesville altar, the new priest recalled the fingers that continued to bring the Eucharistic Jesus to the Mohawks by the Pope’s special permission.

Experiencing that connection with St. Isaac — partaking in offering the same Mass, on the same holy ground — was an intimate moment for Father Vivacqua as a new priest.

“Just to say the word, ‘Jesus,’ they were killed,” Father Vivacqua told the Register after Mass and a long day of giving out first blessings in the shrine’s visitors’ center.

But that moment was just one part of the larger symbol for the Auriesville shrine, which seemed to have closed for good in January. Now, the shrine is going to continue offering the Mass of martyrs and saints, thanks to God’s grace and a dedicated team of Catholics working with the Albany bishop and the Jesuits.

The Rise and Fall of Pilgrimages

The Shrine of Our Lady of Martyrs at Auriesville, N.Y., sits atop a hill overlooking a bend in the Mohawk River. By tradition, the site is believed to be the location of the fortified Mohawk village known as Ossernenon. The Jesuit martyrs St. René de Goupil, St. Isaac Jogues and St. Jean de Lalande laid down their lives sharing the Gospel with the Mohawk Indians. St. Kateri was born here little more than 10 years after their deaths. Many other Catholics, less known to history, also suffered torture in order to share the love of Jesus among the Mohawks at that place.

“There’s a lot of blood that covers these 400 acres,” Father Vivacqua remarked. He had spoken about the martyrs in his homily, because, he said, Catholics need their example more than ever in today’s culture and society. “Young people have to hear these stories and learn what faith these martyrs had.”

For 130 years, from 1885 to 2015, the Society of Jesus operated a shrine on this site. Pilgrims flocked here from all over North America. The Jesuits built the imposing coliseum church, with five separate altars grouped around the center and a capacity for 6,000 worshippers, in 1930. It was built for an age where “going on pilgrimage” was a pillar of Catholic identity.

Robert Rhinedress, the shrine’s groundkeeper, told the Register that old pictures show the coliseum so packed that people crowded all the way up to the steps of the altar for Mass. The shrine hasn’t seen those numbers for decades. What happened?

“Rock ‘n’ roll — at least, that’s part of it,” Rhinedress said, with a half-smile, relating what one of the older Jesuit priests who had once staffed the shrine told him. As the culture changed, many Catholics didn’t hand on this heritage to the next generation.

Last fall, the other shoe dropped for the shrine: The Jesuits announced they no longer had the ability to staff the shrine with priests. The mission appeared at an end. At the start of January, the locked doors simply stated: “Closed.”

A New Partnership Emerges

When Bishop Edward Scharfenberger heard the news of the closure, he quickly moved into action. As bishop of the Diocese of Albany since April 2014, he was aware that the number of pilgrims to the shrine had fallen off. But it had come as a complete surprise that the Jesuits could no longer keep their presence there.

“That’s when I realized something had to be done,” the bishop told the Register. He paid a visit to the shrine and met with the volunteers and benefactors who had raised $2 million in 2015 for funding restorations. The Knights of Columbus’ generous support — a $600,000 grant from national and state chapters — replaced the roof and glass windows of the coliseum and testified to their belief in the shrine’s mission.

The Jesuits had always managed to keep the shrine running in the black, so the bishop was convinced the shrine had enough financial support. All it needed was the priestly personnel to keep it running.

After reaching out to the Jesuits, a plan began to take shape. The Jesuits would hand over the shrine grounds — except the Jesuit cemetery and the ravine where St. Isaac is believed to have buried his companion St. René — to a new nonprofit group, the Friends of Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine, which would operate the shrine and the visitors’ center. Bishop Scharfenberger, the chairman of the nonprofit’s board, would assemble a list of priests who could offer Masses at the shrine every Saturday morning and Sunday afternoon.

Bishop Scharfenberger envisions the Auriesville shrine once again becoming a place of popular pilgrimage. He solicited the involvement of New York’s eight dioceses and recruited people from all over the country to join the nonprofit’s board to broaden its base of support.

“The original North American martyrs were a collaborative team,” the bishop said. “Going forward, we want to develop its potential for passing on the story of its North American martyrs.”

The property transfer could take place within the next four-six months, according to Jesuit Father Philip Judge, the business manager for the Jesuits’ Northeast province. The Vatican has to approve the deal, since it has a vested interest in making sure the shrine remains sacred ground. Father Judge believes that having the Jesuits maintain control over the cemetery and the ravine should allay most of the Vatican’s concerns. The Jesuits have already granted the Friends of Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine a $1-per-year lease to operate the rest of the property.

Father Judge said the Jesuits are enormously pleased with the plan to keep the apostolic mission ongoing.

“We just did not have the personnel anymore to do it ourselves,” he said.

Gift of Martyrs

Most people who come to Auriesville turn off the busy New York State Thruway, taking a right at the solitary Dunkin’ Donuts in front of the toll booth and entering country roads going up and down hills, where speed limits function more as suggestions rather than hard-and-fast rules.

Then the Auriesville shrine suddenly presents itself, with the coliseum visible on the top; and statues of St. Kateri and St. Isaac, by the ruins of an old entrance to the grounds, greet visitors at the foot of the hill. The din of Thruway traffic gives way to the sound of nature, and the rush of time slows, as one climbs the hill’s holy ground and slips into contemplation of the eternal and the human drama of the martyrs who gave their blood to follow Jesus, as well as the saints who came after them.

Every part of the grounds seems to tell part of the martyrs’ story. Affixed on many of the trees at the top are bright-red crosses, symbolizing the crosses St. Isaac would carve into the trees along with the name of Jesus. Some crosses still have “Jesus” inscribed beneath them; others just have “Jesu”; still another has just the “us” remaining.

Jacob Finkbonner, and his mother, Elsa, have made the visit to Our Lady of Martyrs three times since Jacob was cured of the flesh-eating disease in 2006 that should have claimed his life. Because Jacob’s father descends from the Lummi tribe of Washington state, a priest friend suggested the family pray to St. Kateri for a miracle. The Mohawk convert interceded on their behalf.

But their familial connection does not end there — Elsa told the Register that, last year, they discovered that one of Jacob’s ancestors signed a petition more than 100 years ago asking the Vatican to declare the Lily of the Mohawks “Venerable.”

“Being here, able to visit, is something special,” Jacob told the Register after the Mass of thanksgiving. “We can’t take it for granted.”

But back in 2012, when he first visited, Jacob said the shrine looked forgotten. So he joined a telethon to raise money for the shrine, by sharing his story and why it was important for Catholics to support the sacred space. His most-recent visit showed the fruit of the love volunteers have given the shrine since then to beautify it and restore its many monuments. A local artist painted many of the statues, including the Stations of the Cross reliefs, and sculptor Timothy Schmaltz provided his Homeless Jesus statue, which keeps company with the new memorial to the unborn child. The artist plans to unveil a new statue of St. Kateri, standing atop a “globe of turtles,” representative of St. Kateri’s clan and also an important symbol in Iroquois creation myth. Parish Property Management now professionally maintains the grounds.

Elsa said the shrine deserves greater prominence in Catholics’ minds.

“These are spiritual grounds; this is the place where [St. Kateri] was born — here is a landmark at our fingertips. What a privilege, an honor, a gift.”

But there is still work to be done.

“A lot of work had to be done to get the shrine open this year,” Carmine Musumeci, president of the Friends of Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine, told the Register. He said the next project will probably be the renovation of the St. Kateri Chapel.

The nonprofit expects to have federal tax-exempt status by July, according to Musumeci. Then, the group can begin collecting donations in earnest.

Julie Baaki, a volunteer who runs the visitors’ center, told the Register that the long-term goal is to have priests back on the property offering daily and Sunday Masses, as well as hearing confessions. That will mean a priest’s residence, and a new retreat house on the acreage, sometime in the future.

The immediate goal is to get the regular Mass schedule up and running by July.

Rising From the Ravine

No visit to Auriesville is complete without a journey to the ravine. Somewhere on those grounds, the bones of St. René may lie buried, making it a natural reliquary and source of contemplation.

“You can feel the presence of God down there,” said Baaki. Baaki and her husband like to tell their sons how the Jesuit martyrs like St. René were “desperate to be here” and how the martyrs St. Isaac, despite his earlier brutal torture, and St. Jean de Lalande willingly came back to Ossernenon “out of love for God and these people,” even though they knew that torture was certain and death a possibility.

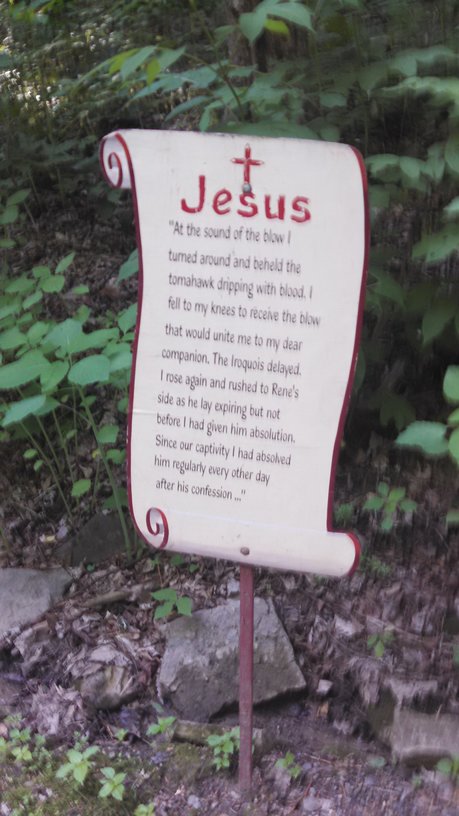

The signposts all the way down the ravine tell the tale of St. René’s martyrdom and St. Isaac’s suffering to give his fellow Jesuit’s body dignity in death. The signs guide pilgrims to a grassy field, where a wooden cross provides a place to meditate on the martyr’s witness.

The place is most silent, and time hangs motionless in the air. The statues tucked by the stream and on the hillside remind pilgrims that the martyrs, and all the faithful departed, shall rise from the grave, just as Jesus Christ did, to share in Christ’s eternal glory.

For Baaki and the volunteers who love Auriesville, the ravine reminds them that Catholics owe a debt to the martyrs, who continue to enrich their faith nearly 400 years later. And so they press on to give back and keep the shrine open as a beacon of evangelism for future generations.

“It’s the least we can do,” she said, “for what they did for us.”

Peter Jesserer Smith is a Register staff reporter.

- Keywords:

- auriesville

- catholic

- diocese of albany

- jesuits

- martyrdom

- north american martyrs

- peter jesserer smith

- shrine of our lady of martyrs

- shrines