Hungary’s Secret Weapon: Catholic Nobility

An Interview With Archduke Michael Habsburg-Lothringen

Archduke Michael Habsburg-Lothringen, former ambassador of the Order of Malta to Hungary, reveals key moments in the Habsburg dynasty’s persistent work to bring Christian values back to Hungary.

Archduke Michael, 78, and his wife, Princess Christiana of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg (known as Christina von Habsburg) have three children — Legionary Father Paul Habsburg, Ambassador Eduard Habsburg, Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See, and Margherita — and 10 grandchildren.

Marriage photo of Archduke Michael and Princess Christina

Archduke Michael, a descendant of the Hungarian branch of the legendary Habsburg dynasty, was brought up not to give up on his ancestral country: Hungary.

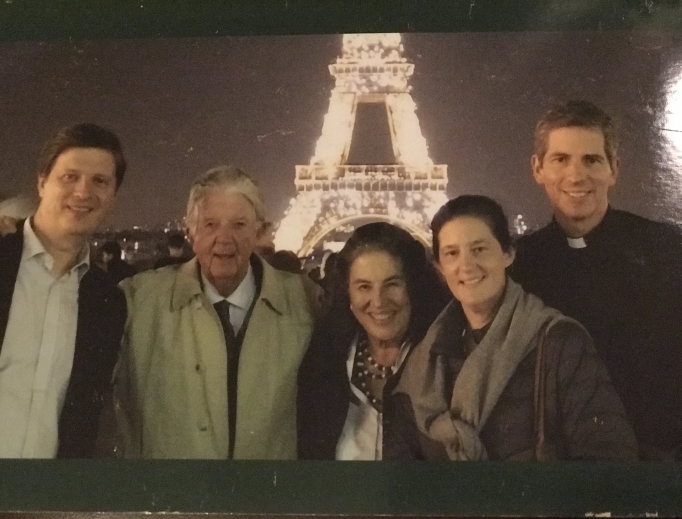

The archduke’s family smiles in Paris.

In the 1980s (despite communism and the presence of Soviet troops) he brought his young family for visits to Hungary and envisaged rebuilding through education and Catholic activities. The aristocrat served as the campaign manager to his cousin Archduke Otto von Habsburg, a 20-year member of the European Parliament’s Christian Social Union of Bavaria Party who served as president of the International Pan-European Union.

Michael reported on his visits to Hungary (as well as East Germany) to Otto, the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s last crown prince (1916-1918).

The archduke has had a discreet influence on Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s education and family laws, although he tends to credit his “best friend,” Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén, a Catholic and leader of the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP), a coalition partner of FIDEZ, Hungary’s governing party for the last decade.

This interview, conducted in Budapest with Register senior correspondent Victor Gaetan, is the second article in a series on Catholic aristocrats who have had an exceptional influence in post-communist Europe, helping to restore civilization — and the Catholic Church.

Your family fled Budapest in 1944, when you were just 2 years old. I understand your grandfather, Archduke Joseph August, and father were jailed during the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, which unleashed a Soviet style “red terror” against all who opposed it, so your family was extremely leery of what the postwar period would bring. Where did you go?

Yes, as the Soviet troops invaded Hungary, we decided to leave because my grandfather, Archduke Joseph, and my father had both been badly treated during the communist overthrow of power in 1919 under Bela Kun. It had happened only 25 years before. We left everything we had behind. My father decided to go as far away as possible, to the end of Europe — where he could steam across the ocean to the U.S., if necessary — and that was Portugal. My grandparents went to Regensburg, Germany, to live in the castle of his brother-in-law, from the Thurn und Taxis family.

I grew up in Portugal, but we knew where we came from, and where we belonged, and where our home had been since 1796, when Palatine Joseph, my great-great grandfather, helped govern Hungary for his older brother [Francis II, the last Holy Roman emperor (1792-1806) and emperor of Austria (1804-1835)].

We were always required to speak Hungarian at home, not Portuguese or English, for I was going to an English school. I’m so grateful to my father for that rule. He always said: “One day, I hope you will return; and, if not, your children or grandchildren will.” This is where we belong. It’s where his heart always remained; and my grandfather’s heart, too. Unfortunately, my father died young, in 1957, at the age of 62.

So I always had this wish and this hope that one day I would come back to Hungary.

Tell me about your life in Portugal.

We first went to Estoril because that was where most of the exiled royal families were living. We were very close to King Umberto II of Italy; in fact, he was the best man at my wedding, if one can say that about a king [Umberto was Italy’s last king, who reigned for a month in 1946]; also, Queen Giovanna of Bulgaria, who was Umberto’s sister. The Spanish King Juan Carlos’ father and mother were there. The comte de Paris lived nearby. I also remember King Carol of Romania, who would sit me on his lap and showed me his stamps. [It was evaluated as the third most valuable stamp collection in the world in 1949].

King Umberto with Princess Christina’s parents (married couple)

My father, who loved the sea very much, dreamed to have a house at the sea, so he found a very large villa, almost free of charge, right on the cliffs, practically overlooking the Atlantic. There, we had these waves coming up on the cliffs all night, and the walls were dripping with humidity, so we quickly realized it was not the best place.

But because we had no money, we were just helped along from one place to another. I think we moved six times in the first year. A family let us stay in a little farmhouse that was very nice, in Carcavelos, where I went to St. Julian’s School. I was 13 years old when I was sent to England for boarding school.

Did you know your grandfather, Archduke Joseph August?

I remember him as an elderly gentleman. He fled Hungary in 1944 and went to Regensburg, Germany, when my family went to Portugal. His wife was a princess of Bavaria.

He was a hero of World War I as a field marshal. He led the Austro-Hungarian army marching on the Italian front. He was involved in seven battles in the Dolomite Mountains; on the Romanian front, as well. He was a great patriot and soldier, very connected to the Hungarian people, known as “Father Joseph” to his soldiers because he also took care of widows and children.

Emperor Karl — Blessed Karl — named him Homo Regius, “Reigning Man,” toward the end of World War I. The position was a sort of personal deputy to the monarch.

But all the Entente countries [France, Britain, the United States] had decided the Habsburgs should not come back to the throne; other organizations such as the Freemasonry, too. The main organization that set off World War I was Freemasonry, and the man who shot the crown prince was a member of the Freemasons, so the idea behind the First World War was the destruction of the Catholic, Austro-Hungarian Empire — which succeeded quite well.

Between the wars, Archduke Joseph August was a member of the parliament’s upper house and served as president of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He was an eminence grise, a quiet influence, behind the scenes. He died at age 92, in 1962.

When did you begin thinking about visiting Hungary?

In 1979 when I went for the first time to communist Eastern Germany with a cousin. We went to visit my maternal grandfather’s grave, King Frederick August III, who was the last king of Saxony. Because of that trip I gathered courage and thought, “I’ll try to see if I can get back to Hungary.”

What was your first trip to Hungary like?

It was in 1980, with my wife and our three children, ages 8 to 13. I was the first in my family to come back to Hungary — in fact, the first to take the risk of traveling behind the Iron Curtain. We went to Budapest, where we were followed all the time [by the secret police], except in the hotel. I told the authorities every day exactly where we were going; then they would pop up.

Our children said, “Why don’t we take them with us in the car, so they don’t have to look for us?”

We drove to Piliscsaba, a former family hunting property. An old man was standing in front of my grandfather’s shooting lodge where he was still working, He stood at attention. It was an incredible moment: for him, after 45 years, to see a member of the family again, and for me, to meet someone who knew my family so well.

A forest guard, or a shooting guard, is a bit like a priest who hears confession: all the things my grandfather —and father — would tell him during the hours they sat on a hide seat, waiting for some deer to come. So I found out a lot about my own family that I had no idea about.

We went to our castle of origin, at Alcsút. The man servant nearly fainted when I rang his backdoor bell and told him who I was. He called all his family and friends and said, “Here they are. I’ve been telling you they’ll be back.” These were very emotional and interesting moments we had together. It was all very beautiful.

I understand that you and your cousin Otto played a role in nurturing the creation of the first democratic party in communist Hungary, in the 1980s. Was there a defining event that marked the fall of communism, in your view?

A key date was Aug. 19, 1989, at the Hungarian-Austrian border, where the Pan Europa youth organizations from both sides decided to have a rally. The event was organized by the Pan-European Youth Organization. On the Austrian side [there was] Otto von Habsburg, and on the Hungarian side [was] the reformed communist minister Imre Pozsgay. My son Eduard and Otto’s daughter Walburga were leading the rally from the Hungarian side. When they symbolically cut open the barbed wire — they didn’t know that in the fields behind them, there was hiding a huge group of East Germans who had been holidaying in Hungary. These people thought this might be the chance to cross the border into Austria — suddenly, 661 people ran for the gap in the fence. The guards at the border had orders to shoot anyone trying to escape “paradise,” as the Communist Party called it. Eduard called me that evening to say it could have turned completely another way because the officer in charge could have said, “Shoot!” and they would have shot all these people. Instead, the officer decided on the spot not to shoot but to let them go.

The next day, Aug. 20, was the feast of St. Stephen, the national feast day in Hungary.

I understand from my interview with Archduke Rudolf of Austria, your nephew, there were Hungarians who hoped his Uncle Otto, successor to the Habsburg throne, would accept the presidency. Do you remember that moment?

I was extremely close to Otto [who died in 2011, the eldest son of Blessed Charles]. I was in charge of fundraising for his European Parliament campaigns. I lived in Munich, and he lived close by, so it was easy to communicate; plus, our wives were close friends.

When I began going to Hungary, I could report to him about the people, who loved him, especially after a film about Otto was shown across the country in cinema houses in 1988 or 1989. Everyone knew he was doing so much to help the country become part of the European Union.

Regarding the presidency, what happened was this: We had parliamentary elections in 1990, but the constitution was still the old one, and it was not clear if the president would be elected by the people or the parliament. There was a moment when the idea grew, from some parties and many people, that they wanted Otto to present himself if the decision was made through a democratic vote. If that had been the case, we knew, based on polling research, he would have been elected by a wide majority.

But then parliament decided it would select the president, so it became a political question, a political game. It was no longer possible for Otto to stand for elections. Mentally, he had packed his suitcases, and we were all maybe even expecting it. It would have been like King Simeon in Bulgaria, who was elected prime minister, without having been in Bulgaria during communism.

Would you consider the principal Habsburg — and by implication, Catholic — characteristics to be: moderation, dialogue, charity, peace, support for just war and proportional retaliation? Given your closeness to Otto and knowledge of his political life, did his lifelong work reflect those principles? What would he counsel Europe today? In particular Hungary?

Archduke Otto’s principles, as have always been those of our family, and as should be for all Catholics, were: building a better world based on the teaching of the Gospel and the Ten Commandments, with an especially strong impact on the protection of the family and life in general.

Archduke Otto’s principal endeavor was to form the opinion of his readers and listeners, especially the younger generation, on the dangers of the totalitarian regimes he had experienced during his long life. He would tell Europe today: Return to your Christian roots! This is exactly what Hungary is doing, at present.

After 1989, you had many options for engagement with post-Soviet Hungary. How did you decide what course to take?

Officially I came back in 1995, but all the years before I had started working with the Catholic Church. I was in business long enough. The important thing was to help rebuild the country from a moral and religious point of view, not do business or politics.

I was already the head of the Cardinal Mindszenty Foundation, our great cardinal whose beatification I’ve been working on for the last 25 years.

My wife and I realized the greatest harm that was done under communism was to the minds of Hungarian people. Streets and houses can be rebuilt, but the damage done to brains is something you couldn’t fix with money alone. So we decided we had to make a school.

We were able to find people around the world to help us. About 18 years ago we started a school, with the help of Robert Zellinger de Balkany, originally from Transylvania. He built his fortune in France.

Now, we have about 720 children, bilingual in English and Hungarian. It is a beautiful school, a great joy for us. It is directed by my son Father Paul’s order. The name of the school was Szent Benedek Primary and Secondary School. With the approval of the Vatican, it is now St. Pope John Paul II School Centre.

You also helped re-establish the Order of Malta in post-communist Hungary. Tell me about that, please.

My grandfather was the founder and first president of the Hungarian association of the Order of Malta, but during communism the members were largely in exile. Then, in 1989, the border reopened, and there was a huge wave of people who poured into Budapest.

Csilla von Boeselager, a Hungarian-born dame of the Order of Malta, together with Father Imre Kozma, mobilized the German order; and within 48 hours, they set up enough tents to receive and care for over 60,000 refugees during the months to follow.

This was entirely within the spirit of this 900-year-old order founded to help the sick and the displaced. People saw the cross of the order on the tent roofs, and this made the order known and loved in Hungary.

You served as ambassador to Hungary of the Order of Malta, 2015-2017, the period of the migration crisis in Europe. What was that experience like?

Up to 8-9,000 people, refugees and migrants, were coming each day at the height of the crisis. My wife and I went every evening for months and months under the train station in Budapest, where people were packed very tight. They were waiting to carry on and get to Germany. They kept saying, “Merkel! Merkel! Where is Merkel?” She had invited them to come to Germany, but the border to Austria was closed.

They did not want to stay in Hungary. They wanted to get to Germany. We took care of them and provided food and medical care, together with our team of volunteers from the Order of Malta, with the Palestinian ambassador translating, and a Jordanian doctor. Every night, my wife and I were there.

There were masses of children; many women were pregnant. Children were born in the station. It was an incredible experience. Finally, Austria opened the borders, and they were able to carry on with their journey. The experience left a deep impression on us.

Your family designated you to coordinate work on behalf of Cardinal Josef Mindzenty’s canonization. In the process of collecting material on his case, what impressed you the most?

Certainly, the courage he had. When the communists were taking over, he came back from Canada to Hungary, in the worst year, 1947, and he proclaimed it the “Year of Our Blessed Lady.” He personally led pilgrimages to all the shrines of Our Lady: Over 3 million out of a population of 9 million went with him to those shrines throughout the year. At the same time, the communist regime was trying to close schools, close the convents, get rid of the priests, and he was still there, every Sunday, bringing people together around Mary.

He followed Pope Pius XII — no compromise.

Yes! By the way, I’m Michael Pius, because Pius XII is my godfather. Well, he couldn’t come to the christening because he was pope by 1942, but Eugenio Pacelli [future Pope Pius XII] came to Budapest in 1938 for the World Eucharistic Congress and made friends with my parents. When my mother was expecting her eighth child, that’s me, she wrote to the Pope. The Holy Father answered very kindly and sent Cardinal Angelo Rotta to represent the Pope at my christening, in the palace of my grandfather.

The World Eucharistic Congress will be held again in Budapest this year, Sept. 13-20.

Pope Francis declared Cardinal Mindszenty “Venerable” on Feb. 13, 2019. What was that day like for you?

We were waiting for this decision to go to the Holy Father, because as soon as the Holy Father signs, the person is no longer a “Servant of God,” but “Venerable.” I was praying and hoping it would happen before we opened a conference in Budapest on the persecution of Christians behind the Iron Curtain. The Pope was in Panama, and I was hoping that Cardinal [Giovanni] Becciu [head of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints] would find the moment [to give the Holy Father the file].

My son Eduard was already texting me at 6am, saying, “My secret service is telling me today something might be happening.” The tip was not from the congregation, but from a journalist. Then, at 10 or 10:30am, it happened. I was given the green light in the parliament’s upper house. I went up to the speaker’s desk to announce the Pope had signed the document, and everyone got up, and there was an incredible applause — which I did not anticipate.

What comes next?

Now comes the most important step. For a non-martyr, a miracle has to be proven, but all his life was a martyrdom, including prison and including the years in the embassy.

That was in February 2019. Is there a potential miracle?

There was a potential miracle. An old man came home to die with a terminal illness. Then, as a result of his family’s prayer for the intercession of Cardinal Mindszenty, he was completely healed. He died three years later [of something else]. On a team of doctors, five said this was not a miracle. Only one said it was. We were extremely upset about this and very disappointed. But we do not give up and keep on praying!

Fascinating. Shifting gears to a subject close to home, you and your wife must be very proud that one of your sons joined the priesthood. When was Father Paul ordained?

Father Paul was ordained in Rome in 2001 at Santa Maria Maggiore, together with 44 other priests of the order of the Legionaries of Christ.

We were helped along the way by someone, the Gospa, Our Lady of Medjugorje in that place of apparitions, where we have been going for 30 years.

Growing up in Portugal, we went to Fatima every year, so when I heard that Mary was appearing just 1,000 km (621 miles) away, I took my wife and children, and we started going there, trying to understand what was going on.

I am sure that my son’s vocation happened, in part, there. The message of our Lady of Medjugorje to pray, pray the Rosary and fast at least once a week was so convincing.

We tried to go to Mass every day, and the children were at the age that maybe they would not listen to their parents, but they listened to the Gospa.

My priest-son just went on doing that, and Mary took it off our hands, regarding telling him what to do and what not to do. It was much better that she did it, and it was more convincing that way.

I’ve met your son, Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See, Eduard Habsburg. He has been very effective in his position, and he and his wife have given you six grandchildren. Does your daughter, Margherita, have children?

Margherita and her husband, Austrian Count Benedict Piatti (the family originally came from Italy), who is a practicing doctor of neurology, have four children, a girl and three boys. Their daughter, at present, attends Franciscan University in Steubenville, Ohio, and loves it.

How do you feel living in Hungary, which is criticized by Brussels, the European Union and Washington?

I have moved 24 times in my life since I was born. Now, I have a feeling of having finally come back to base, back to harbor, where my ancestors were. Trying to help this country recover from the terrible years of communism takes a long time to repair, but we are fortunate that we have this fantastic Christian government. We have a new constitution, a constitution that begins with the word “God” — probably the only one in the world.

It replaced the communist one of 1949, and the new one says that the family has to be protected by the constitution and that marriage is between a man and woman — full stop. So we are happy to live in this country that is safe and secure, with little criminality, and we are just happy to do our work here.

Can you name another Hungarian noble who has had a major, positive role in restoring post-communist Hungary?

A good example of a nobleman who stayed in the country and is now very much responsible for the country’s success is our deputy prime minister, Zsolt Semjen. He’s my best friend.

Semjen, 57, is in charge of the party called KDNP, Christian Democratic People’s Party. He is kind of the moral backbone of this country.

Semjen is fantastic, and he is a nobleman, though many don’t know it. His family was made noble in the 16th century by my ancestors.

How do you explain the persistent criticism of Pope Francis?

It is something I can’t imagine happening 20 years ago.

This pope, from Argentina, is very different from Europeans. They say he approaches too many subjects and tries to find new solutions. Very traditional Catholics worry and think they have to criticize him, but he hasn’t done anything that doesn’t conform to the teachings of the Church. The pope is the Pope. He is inspired by the Holy Spirit and leads the Church to God. I think it is completely wrong to criticize him.

I think all of this is highly exaggerated, and nothing has happened, except maybe he opens a lot of lids without closing them tightly, to use a cooking metaphor. We hope and pray for the Pope. They [Catholics who criticize the pope] should, rather, pray more for him, instead of criticizing him.

Register senior correspondent Victor Gaetan is an award-winning international

correspondent and a contributor to Foreign Affairs magazine and The American Spectator.

- Keywords:

- catholic europe

- habsburg family

- hungary

- victor gaetan