A Monk’s Life: Following St. Benedict in the 21st Century

Abbot ponders the challenge of modern monastic vocations.

Recently, the German news magazine Der Spiegel ran an article on the decline of religious communities in Germany. It makes for depressing reading, telling of large religious houses with ever-dwindling communities. In 1960, there were around 110,000 religious in Germany; in 1999, there were 38,348; now, there are about 17,900.

The article detailed how the religious that are left are aging. The combination of declining numbers and increasing age makes a sustainable community life in some religious communities almost impossible; it also means that attracting younger vocations is difficult.

This crisis in religious life is not only occurring in Germany, however. Across many parts of the Western world there exists a similar problem — with, of course, some notable exceptions in communities where monastic vocations continue to appear steady.

In an interview with the Register this September, Dom Xavier Perrin, abbot of Quarr Abbey, a house of the Solesmes Congregation on the Isle of Wight, an island off the south coast of England, talked with penetrating perception about the current challenges in helping nurture vocations to the monastic life today.

Dom Xavier was appointed as prior administrator of Quarr Abbey in May 2013 and was elected abbot in May 2016. He entered monastic life in 1980, when he was 22 years old. He guides the small community of less than 10 monks in fidelity to the Rule of St. Benedict in prayer, work and community life. The abbey keeps bees and pigs and runs a busy guesthouse. The abbey also has an intern program for young men who come and spend a few months simply living and working in the monastery and on its grounds.

Challenge and Vision

“I see two main challenges” in nurturing monastic vocations, relates Dom Xavier, who, before he came to Quarr, was choir and novice master and later prior in the French monastery of Kergonan, Brittany: “On the one hand, there is the crisis of faith in the Western world. Where Christianity is not strongly rooted in families and society, it should be no surprise that fewer young people are able to hear and answer God’s call.” There can sometimes exist “a fascination with monastic life,” Dom Xavier says, “but without the basic knowledge of the faith, it is always going to be difficult to enter into monastic formation.” As a result, he suggests that there may be a need for places where young people can receive “a basic catechesis, experience sacramental life and be prepared for partaking in the life of the wider Church before they consider a specific vocation.”

The second challenge Dom Xavier sees is that we are going through “an anthropological crisis.” The very understanding of what it is to be a man or a woman is becoming very confused, he observes, as is an understanding of how human life should begin and rightly end. This crisis, he says, is really one that involves “the relationship with our Creator. Man cannot find his or her right place in the creation. There is no stable identity.”

While Dom Xavier recognizes that monastic life can go some way to help heal novices and monks in these two areas, he is equally clear that, “if the ground is not prepared — a simply human and Christian ground — the seed of a vocation will not flourish. We need places where young people are taught a correct vision of their own humanity.”

There are other challenges that he perceives threatening the flowering of monastic vocations. There is, for example, the hyperconnectivity of the virtual world, which militates against the desire for and achievement of that contemplative separation from the world that has always formed an essential part of monastic life; there is the increasing prevalence of one-child families, which, he sees, can “make it very difficult for parents to ‘give’ one of their children to the Lord”; and there are ongoing confusion and tensions within the Church: All these factors pose significant challenges to monastic novice masters and mistresses supporting and forming those called to the monastic life.

Springs of Hope

So why are some newer monastic communities attracting vocations, while some of the more established ones are not?

Dom Xavier responded with humility and simplicity. “Vocations are a gift of God, and have always been. … Life,” he says, “is always a gift,” drawing the analogy of monastic vocations to the gift of children in marriage. A great number of vocations can never be taken for granted nor considered a consequence of the good works or the good choices of a community. “That said,” he goes on, “some communities seem to attract more vocations than others.” His reflections on why this may be the case are thought-provoking and illuminating. “It can be,” he observes, “because of the personality of their leader, or the novice master or the guest master. It can be because there are already a few young people [in the community]; hence, hope for a future. It can be that one element is especially attractive: This might be the liturgy, or the hospitality or the quality of doctrine. It can be that the image given by the community is more positive: One gets the impression that something new is beginning, which will bring life.”

These newer communities, or newer foundations of old orders, often present, Dom Xavier feels, “a great vibrancy coupled with an idealized image of what monastic life should be. Young communities can be full of energy and able to follow high standards of observance: long offices, visible prayer times, such as adoration and the Rosary, coupled with strict discipline.” To youth, such idealism is attractive, he says. But, he adds, “this can also be slightly deceptive.” Nevertheless, he says if this energy and zeal are coupled “with good doctrine rooted in the teachings of the Church and a balanced leadership, the excesses of youth will pass away, and there could be beautiful fruits in the future.” Quite simply, Dom Xavier is clear that when a postulant joins a monastic community, that person should do so for “good reasons and not as a result of superficial impressions.”

Lessons From Experience

So what can more established, if now smaller communities, like Quarr Abbey, teach newer ones? Dom Xavier is clear that “established communities would be foolish to boast of any superiority. If they have been and are faithful to their call, they will have the experience and wisdom that come with the years.” He explains, “In a community that has existed for a long time, there will have been many experiences, good and less good, and lessons will have been handed over to succeeding generations [in the monastery]. It becomes part of a community wisdom.”

This is especially the case, Dom Xavier says, in a community where “the gifts of discernment and balance” are present. “These gifts can touch the question of vocations — discernment of the right aptitudes for the life — and the whole balance of life. There can always be a danger to overdevelop one dimension [of monastic life] whilst forgetting about others. As a community, you can have too much prayer, or too much work, or too much common life, or too much dependence on the leader, or too many pastoral activities.”

“The wisdom of monastic life,” Dom Xavier also notes, “wants to balance all these elements. It is a supple adaptation to the varying circumstances of persons and of life. It becomes less and less a discipline for everyone to follow, and more and more a space where persons can flourish in their gifts and in real communion with others.”

“Discernment should be the quality of leaders,” he comments, but also, echoing St. Benedict, “of all community members, as all are free children of the Father.”

With that in mind, and as abbot of a monastic community, what would Dom Xavier consider the essence of a monastic vocation? “A monastic vocation is a call from God to follow Christ in the form of life of a monastery: a life shaped by separation from the world,” but also a life shaped by “liturgy, community, obedience, silence, work (manual and intellectual). Basically, it is a call to love in the Church as Christ loved his Father (in adoration, praise and worship) and his brethren (through intercession, hospitality and service). Hence the key element is desire. No one can remain in a monastery without a desire for God that is greater than anything else. St. Benedict calls that ‘searching for God.’”

From the Ground Up

For over a century now, Quarr Abbey has been a place of searching for God. Monks from the French monastery of St. Pierre at Solesmes, the famous abbey and center of Gregorian chant refounded in the 19th century by Dom Prosper Guéranger after the ravages of the French Revolution, came with their abbot, Dom Paul Delatte, to Appuldurcome House on the Isle of Wight in 1901. They arrived as exiles, fleeing the anti-clerical laws then attacking religious life in France. In 1907, the monks bought Quarr Abbey House that lay beside the ruins of the 12th-century Cistercian monastery of Quarr, which had been suppressed during the English Reformation.

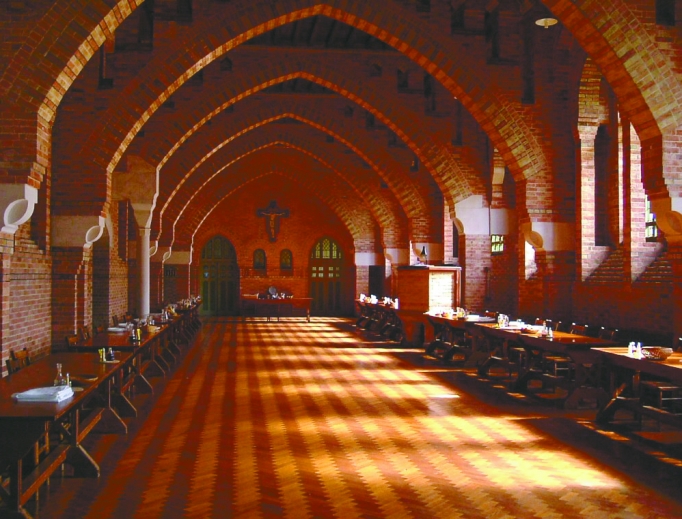

One of the monks of Solesmes, Dom Paul Bellot, was also an architect and set about designing a monastery and abbey church suitable to the monk’s needs and spirit. In April 1911, construction of the church began. Completed the following year, it was consecrated on Oct. 12, 1912 — a magnificent building of pink and honey-colored brick. The guest house was finished in 1914, with its first guest being the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain. During the First World War, the guest house was used for convalescing soldiers. The writer Robert Graves, who wasn’t Catholic but greatly respected the monks in their work, stayed there for a short time healing from his wartime experiences, and mentioned the fact in his celebrated memoir Goodbye to All That (1929):

“Hearing the Fathers at their plain-song made me for the moment forget the war completely,” Graves writes, adding, “I half-envied (the Fathers) their abbey on the hill, and admired their kindness, gentleness and seriousness. … At Quarr, Catholicism ceased to repel me.”

By 1921, the political situation in France having improved, some of the monks returned to Solesmes. Twenty-five monks remained, however, and as part of the Solesmes congregation, they continued monastic life at Quarr. The first English monk of Quarr was professed in 1930; and in 1964, the first English abbot of Quarr was elected, Dom Aelred Sillem.

Wide-Open Future

Despite the many challenges, Dom Xavier sees the future as holding unexpected possibilities for monasteries and the wider Church. “Monasteries will be more and more sought after by Christian laypeople wishing to find places where the Christian life is lived out on a daily basis. Through working in collaboration with laypeople, the monasteries will be places of welcome for men and women of all sorts looking for peace, meaning, direction and wishing to receive a word about life, and maybe also about Christ.” He added, “I see monks and nuns not so much speaking a lot or being very active in the pastoral area, as welcoming with simplicity, and drawing people to Christ by the silent witness of their lives, given to adoring and serving God in the joy of the Gospel.”

The monastic bell tolls for vespers, and Dom Xavier readies to go.

A couple final questions were posed: First, for anyone wondering about this life, what are the signs the abbot looks for in any future monk?

“I would say: first a fascination for God, an attraction toward his unfathomable mystery; the intuition that God suffices, that it is enough to adore him, that it is worth leaving all and all things aside to make oneself free to search for him alone. A second sign is a love for prayer in both its liturgical and private forms. A third sign is a desire for communion and community life, living in a stable human group, becoming a brother, serving God in and with others. A fourth sign is an intuition that I cannot by myself alone go to God; I need guidance; I need to learn, to be a disciple; I want to obey.” The abbot concludes with what for him is essential in all this: “a personal relationship with Christ: being drawn to his teaching, his sacraments, his life, his Church, his Person, his Father in heaven and his mother Mary.”

And, secondly, other than a divine calling, what is the most fundamental human requirement needed for this kind of relationship with God?

“When God has put the desire in your heart, it will flourish if you have a balanced judgment, a strong will and reasonably good health. Think of someone engaging in long-distance running. That will give you a good idea of the qualities of strength, economy and perseverance required for the monastic challenge.”

And, with that, Dom Xavier leaves for vespers to sing the Divine Office once more.

K.V. Turley is the Register’s U.K. correspondent.

- Keywords:

- k.v. turley

- monasticism

- monks

- vocations