Averting Nuclear Armageddon — in October 1962 and Today

COMMENTARY: Sixty years ago, it took the skill and resolve of key statesmen and religious leaders — in Washington, in Moscow, at the Vatican — to pull the world back from the precipice.

It is ironic and scary that 60 years after the Cuban Missile Crisis that brought the world’s two superpowers to the brink of nuclear Armageddon, President Joe Biden warned of possible nuclear “Armageddon” again, this October 2022, and once again with Russia.

Biden has been harshly criticized for that language, accused of hyping an already grave situation between Putin and the Ukraine and of fanning the flames with unnecessarily incendiary rhetoric. Personally, I think Biden’s warnings are apt. I’ve been stating for months that the potential for a desperate Vladimir Putin to escalate to the level of using nuclear weapons is frighteningly real. A Putin whose army is defeated on the battlefield is a Putin who may well resort to something catastrophic, as we feared in October 1962.

The situation in October 1962 — ironically, for America’s only other Catholic president, John F. Kennedy — was dire. JFK faced a grim scenario that looked like it might spiral out of control. It was a grave situation difficult to hype. In fact, Kennedy struggled to communicate to Americans just how alarming the situation was without overly alarming them.

It all began on Oct. 14, 1962, when an American U-2 spy plane doing regular reconnaissance over Cuba caught images of what appeared to be Soviet missile sites. This had been among America’s worst fears since Fidel Castro had come to power in January 1959 and allied with the USSR. The prospect of a legion of Soviet nuclear missiles fired from Cuba at American soil, leading to nukes fired in retaliation by the United States against Cuba and the USSR, and then the USSR against the United States, and then Western Europe and Eastern Europe brought into the fray — killing countless millions of people — was truly a doomsday scenario.

Kennedy went public with the U-2 finding in a dramatic nationally televised speech on Oct. 22. Americans were terrified. They dashed to grocery stores to buy up all canned food and supplies, and many of them literally started digging bomb shelters. Popular culture had been filled with fears of nuclear war. You could see it in movies and on TV. Now it looked like it might become a reality. Everyone readied to duck and cover.

As for President Kennedy, he faced hard choices. His advisers didn’t know whether the missiles were armed yet with nuclear warheads. Thus, some military advisers urged strikes on the missile sites immediately, before the weapons became nuclear. But if he did, countered Kennedy, he would be seen as the aggressor, killing not only Cubans but Russians. The Cold War would become a hot war, with Kennedy perhaps perceived as starting it by going on the offensive. His closest adviser, Robert Kennedy, said he didn’t want his brother to become a “Tojo in reverse” — a reference to the Japanese leader who authorized Pearl Harbor.

The nightmare scenario terrified all of humanity, from Washington to Moscow to every capital. But there were two extraordinary exceptions. There were two lunatics who welcomed Armageddon from ground zero in Cuba: Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. The fact that they did, and why, must be known and remembered, especially given the odd admiration for Fidel and Che by many misinformed young Americans.

“If the nuclear missiles had remained, we would have fired them against the heart of the U.S., including New York City,” Che gleefully admitted in November 1962 to Sam Russell of Britain’s Daily Worker. “The victory of socialism is well worth millions of atomic victims.”

Che was willing to fire those atomic weapons and launch a nuclear war that he understood would lead to the liquidation of Cuba. Che biographer Philippe Gavi said that the Argentine revolutionary had bragged that “this country is willing to risk everything in an atomic war of unimaginable destructiveness to defend a principle.”

The principle was communism.

Keith Payne, president of the National Institute for Public Policy, recounted how “Che Guevara specifically said that he was ready for martyrdom” (that is, to be an international martyr to the religious-like cause of communism) and “ready for Cuba, as a country, to be a national martyrdom.” Payne quotes the response of a shocked Anastas Mikoyan, the leading Soviet official under Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who responded to the martyr-like fanaticism: “We see your willingness to die beautifully. We don’t think it’s worth dying beautifully.”

Che was an unhinged zealot who described himself as “bloodthirsty.” Fidel Castro was no better.

If Fidel would have had his way in October 1962, Cuba would have ceased to exist. The fact is that Fidel actually recommended to Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev that they together launch an all-out nuclear attack upon the United States and even urged Khrushchev to do so if U.S. troops invaded the island.

This is no secret. Castro openly admitted it. Robert McNamara, JFK’s secretary of defense during the Cuban Missile Crisis, was taken aback by Castro’s candor when the two men publicly discussed the incident 30 years later in an open forum in Havana. Fidel told McNamara flatly, “Bob, I did recommend they [the nuclear missiles] were to be used.”

In total, said McNamara, there were 162 Soviet missiles on the island. The firing of those missiles alone would have led to (according to McNamara) at least 80 million dead Americans, which would have been half the U.S. population, plus added tens of millions of casualties.

That, however, is a mere conservative estimate, given that 162 missiles were far from the sum total that would have been subsequently launched. The United States in turn would have launched on Cuba and also on the USSR. President Kennedy made that commitment clear in his nationally televised speech on Oct. 22:

“It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

In response, of course, the Soviets would have launched on America from Soviet soil. Even then, the fireworks would just be starting: Under the terms of their NATO and Warsaw Pact charters, the territories of Western and Eastern Europe would also start firing.

Once the smoke cleared, hundreds of millions to possibly more than a billion people could have perished. If Fidel Castro had his way, he would have precipitated the greatest slaughter in human history.

Would that have been good for Cuba? Fidel weighed in on that one, stating the obvious to McNamara: “What would have happened to Cuba? It would have been totally destroyed.”

Fidel didn’t care, and neither did his comrade Che. They were ready for martyrdom. As McNamara said of Fidel, “He would have pulled the temple down on his head.”

To Fidel and Che, Marxism was their faith, and they desired to be martyrs to the faith.

JFK, an intensely anti-communist Catholic, understood that about communists. He loathed Fidel and Che and what they were doing to Cuba, which had once been arguably the most Catholic country in the entire Western Hemisphere. (Read Thomas Merton’s stirring account of Cuba’s beautiful Catholicism in his The Seven Storey Mountain.)

Even the atheist-communist Soviets were stunned at such unbridled zealotry by Fidel and Che. In fact, it helps explain how this crisis was averted. Nikita Khrushchev quickly realized he was dealing with lunatics and better immediately remove the missiles.

Nikita Khrushchev’s son Sergei, in his seminal three-volume biography of his father, chronicled the Kremlin’s astonishment: “[Castro] had to inform Moscow as quickly as possible of his decision to sacrifice Cuba.” The Soviet ambassador to Cuba, Alexander Alekseyev, was so stunned that he stood frozen as he listened to Castro tell him: “If we want to avoid receiving the first strike, if an attack is inevitable, then wipe them off the face of the earth.” Without waiting for an answer from the speechless Soviet ambassador, Castro started writing his feelings on paper, which “seemed like a last testament, a farewell.” Fidel was ready to go up in a giant mushroom cloud for Marxism.

Nikita Khrushchev now knew he had to act without hesitation to get the nukes away from these madmen. He met with the top Soviet officials in the “code room” of the Soviet Foreign Ministry very late on a Sunday night and ordered, repeatedly, “Remove them, and as quickly as possible.”

As for Fidel, he was “furious,” said Sergei Khrushchev: “Castro was mortally offended. He had made up his mind to die a hero, and to have it end that way.” He now considered Nikita Khrushchev “a traitor.”

Thankfully, the world averted nuclear war through the steady leadership of President Kennedy and thanks to Nikita Khrushchev removing the Soviet missiles.

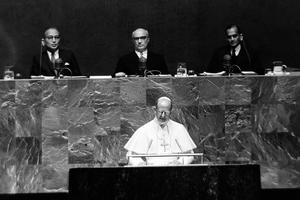

It should also be acknowledged — and known among Catholics — that Pope John XXIII played a role in trying to mediate the conflict. The Pope had received a direct message from the Catholic president conveying the high stakes. Upon reading Kennedy’s dispatch, John XXIII drafted a statement that went to the embassies of the United States and the USSR. The Pope read his message on Vatican Radio. It appeared in newspapers worldwide, including Pravda, which headlined this specific appeal from the pontiff: “We beg all governments not to remain deaf to this cry of humanity.” The Kremlin clearly appreciated and approved of the Pope’s intervention. Two days later, Khrushchev agreed to pull the missiles.

Historian Ron Rychlak described John XXIII’s role as “crucial” but “often overlooked.” Indeed, it is.

And so, in October 1962, nuclear Armageddon was averted. In October 2022, we pray that any use of nuclear weapons by Moscow will again be averted. Sixty years ago, it took the skill and resolve of key statesmen and religious leaders — in Washington, in Moscow, at the Vatican — to pull the world back from the precipice. Do we have such men with such abilities in those posts today?

We shall find out.

(Click here for Professor Kengor’s October 2019 lecture on the Cuban Missile Crisis, broadcast by C-SPAN.)

- Keywords:

- vatican missile crisis

- nuclear disaster

- president john f. kennedy

- cuban missile crisis

- macnamara

- soviet union

- joe biden

- vladimir putin