7 Lessons From the Life and Ministry of Blessed Michael McGivney

COMMENTARY: Reflecting on the example of the new beatus can stretch the expectations and broaden the horizons of contemporary U.S. Catholics.

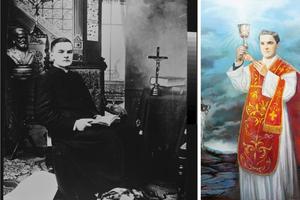

The saints are supposed to “stretch our expectations” and broaden our “missionary horizons.” So said Bishop John Barres of Rockville Centre, New York, on Saturday a few hours after the beatification of Father Michael McGivney, parish priest and founder of the Knights of Columbus.

It’s quite possible, due to the ubiquity of the Knights in American Catholic life, that Blessed Michael could become the best-known American saint or blessed — at least until Archbishop Fulton Sheen is beatified.

So what lessons might be drawn from the life and ministry of Blessed Michael? How might the new beatus stretch our expectations and broaden our horizons?

I suggest seven ways Blessed Michael might do just that.

Young Clergy

Father McGivney died at age 38, having spent only 13 years as a priest. Saints do not have to be old — St. Thérèse of Lisieux and Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati died at 24.

McGivney founded the Knights of Columbus while he was still a curate (assistant) at St. Mary’s in New Haven. He was not the pastor. He managed to found the Knights of Columbus as a curate, a project which required him to work with men of affairs many years his senior in age and experience.

Very few new priests today get seven years to be a curate; many are pastors — sometimes of more than one parish — before their fifth ordination anniversary. The example of Blessed Michael teaches us to be open to the initiatives and energy of young clergy; it is not something to be feared. Had his pastor thought that the young Father McGivney should “know his place” and “wait his turn,” would the Knights of Columbus ever have come to be?

Lay Leadership From Men

Blessed Michael was decades ahead of his time in empowering — as we would say today — laypeople to lead. He declined to be the executive head of the Knights, insisting that it be governed by laymen, as it is to this day. He remained as chaplain.

In the 21st-century parish there is lay leadership aplenty; in that sense, McGivney does not stretch our expectations anymore. But he does broaden our missionary horizons if we think about Catholic men, from teenagers to mature adults. Blessed Michael’s special talent in attracting men to live their faith devoutly and be proud of their Catholic identity is needed today. The great number of men’s ministries that have popped up to address this need now have a new patron.

Prisoners

During the day of the beatification ceremonies, the most commonly remarked pastoral success of Blessed Michael revolved around his dozens of visits to Chip Smith, a young man on death row who was condemned for killing a police officer. Father McGivney helped him to return to the faith, and he went to his execution a profoundly converted disciple nourished by the sacraments. Many devotees of Blessed Michael suggest that Chip Smith was already in heaven when his spiritual father got there.

No country needs a patron of prison ministry more than the United States, the world’s leader in incarceration. With 5% of the global population, the United States has 25% of the world’s prisoners. More Americans are incarcerated per capita than in totalitarian states, and U.S. jails contain six to 12 times the numbers of inmates of other democracies. It seems unlikely that America’s singular policy of mass incarceration will end soon, so the Church’s pastoral care for the imprisoned — justly and unjustly — is a pressing priority.

Immigrants

Blessed Michael reminds U.S. Catholics that theirs is an immigrant Church, long suspected of being alien to the American way of life. Irish Catholics like the McGivneys, who fled the potato famine to cross the Atlantic, were only the first of waves of immigration that built up the Church. American Catholicism has grown more by immigration than evangelization, with Italians, Germans, Poles and others being followed by Mexicans, Filipinos and Vietnamese.

Practical care for immigrants, advocacy for their rights and their full inclusion in the life of the Church is not a project of choice for the Catholic Church in the United States; it is its deep identity.

Inclusion of the Poor

The Knights of Columbus was founded to address an ancient biblical need, the care of widows and orphans. The genius of Blessed Michael was that he did not envision a Catholic welfare agency for their sustenance, but rather a “fraternal benefit” — insurance — society that would allow the poor to cooperate with others to meet their needs. Orphans did not become wards of others, but were looked after by their own families, provided for by the foresight of their own deceased fathers.

While the Knights today are a powerhouse of financial donations and volunteer hours in direct, practical works of charity, the McGivney vision is at its best when it seeks to include the poor in the circles of collaboration, creativity and productivity that arise from the dignity of work and provision.

Family Unity

In Blessed Michael’s time, the death of the breadwinner did not only mean poverty; it meant the state taking the children away from the widowed mother unless she could put up a surety demonstrating the means to raise the children. The desire to keep families together animated Blessed Michael just as much as keeping them out of poverty.

Today the problem of family division caused by poverty has been reversed; families that never form often end up poor. Fractured families are also catastrophic for the transmission of the faith; while no guarantee, stability in family life favors handing on the faith. Blessed Michael reminds us that the natural good of family life is part of God’s plan of salvation.

Cultural Disdain

New Haven, a port town on Long Island Sound, was close enough to get the attention of The New York Times. When the Catholics of New Haven built their first church, St. Mary’s, in the midst of the civic Protestant elites, The Times’ headline summarized the disdain in which Catholics were held: “How an Aristocratic Avenue Was Blemished by a Roman Church Edifice.”

Blessed Michael’s life is a reminder that American culture is always uneasy with Catholicism; noted Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. regarded “the prejudice against [the Catholic Church] as the deepest bias in the history of the American people.”

The New York Times today does not reflect the original U.S. Protestant prejudice against Catholicism; it reflects instead a new secularist prejudice against Catholicism. American Catholics today are tempted across a wide range of professions to downplay their Catholic identity if they wish advancement or influence. Not a few of them will have to embrace the soft martyrdom of suffering for the faith. The life of Blessed Michael — now confirmed by the Church to be in the heavenly homeland — is a reminder that we have here no abiding home and, increasingly, not even a hospitable one.