The Lord Is at Hand — Give Thanks to Him Always

To think of the spiritual life in terms of grim, unceasing duty is repellent to anyone intent on loving and serving the Lord.

If we are serious about the spiritual life — and unless we are, there’s not much point in having one — then we need to begin by giving thanks. Rejoicing, too. And not just once or twice, but every day and in every way. To God, of course, for whom not even a sparrow falls but that our Heavenly Father knows it and, more to the point, wills that it happen.

The Apostle Paul is perfectly clear about this, even to the point of redundancy, in his stirring exhortation to the Christians in Philippi:

Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, Rejoice. Let all men know your forbearance. The Lord is at hand. Have no anxiety about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which passes all understanding, will keep your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus (4:4-7).

We have our marching orders, then, which are to serve God, whom we aspire to know and to love amid circumstances not conducive to either, so that it may please him to welcome us one day into Paradise. To pull off that miracle, which is the whole point of being a disciple, will require nothing less than a heart overflowing with joy. Abundantia cordis, from the fullness of which everything else flows, including the words we will need to speak either of consolation or conviction.

Concerning what exactly? That Christ is the center of the universe, Lord of history and of psychiatry; in short, the reason for every season, including those seasons of the self in which, all too often, we substitute ourselves for him. Not realizing, of course — indeed, often forgetting on purpose — that God alone is both origin and finality of all that exists, and who alone sustains us along the way.

“Thee, God, I come from,” exclaims Gerard Manley Hopkins, “to Thee go / All day long I like fountain flow / From thy hand out, swayed about / Mote-like in the mighty glow.”

Not to know this, or failing to put it into practice, causes the whole spiritual life to grind to a halt, leaving the soul bereft of hope, shorn of the joy that alone enables us to rise above adversity. A joyful heart, in other words, has simply got to be the chief staple of our life, the foundational fact upon which everything else depends. Not an incidental or peripheral affair, the superficiality of which will have no staying power whatsoever. But one that is absolutely anchored to Christ, to the fact that we belong to Christ and that it is he who defines our existence at every moment and in every circumstance.

Father Daniel Considine, an old school Jesuit, whose sound advice on the spiritual life may still be found in certain parish vestibules, writes, “Our difficulties are so great, our enemies so many, that unless we are supported by joy, we shan’t be able to do what God wants us to do.”

It is a point of great consequence that he is making here, which is that to think of the spiritual life in terms of grim, unceasing duty, of obligations painfully undertaken, is not just wrong but repellent to anyone intent on loving and serving the Lord. “We are never so much fitted to cope with the difficulties of the spiritual life,” he reminds us, “as when we are in a state of joy.”

In fact, the greater the difficulties we face, the more acute the hardships that await us, the more we shall need to draw upon those deep wellsprings of joy. And because they are found in Christ, they will never dry up. There are no exhausted cisterns for those who draw water from the springs of Christ. And the source, the provenance for those currents of joy that pulsate, that course joyfully along the streams of the soul, cannot be taken or diverted from us by either demons or men unless we give them our permission.

And why would anyone one want to do that? Because what justifies the experience, constantly burnishing it with lyric and unremitting expression, is the fact that we are loved. Right down to the bottom of our toes. “Christ’s possession of me,” writes Servant of God Luigi Giussani, “is my liberation.”

How intimately, how ineluctably this fact is bound up with the experience of time, with the sense we have that our lives are forever in motion — that the fullness of life, of love, is not given all at once, never in a definitive or final way but as intimation or hint of some yet more sublime consummation still to come.

Eliot’s ever-elusive “still point of the turning world,” toward which we are to move with courage and constantly renewed resolution. Hence the importance of patience, of asking God, as he repeatedly does in “Ash Wednesday,” his great poem of conversion: “Teach us to care and not to care / Teach us to sit still / Even among these rocks, / Our peace in His will …”

And in the culminating movement of Four Quartets, Eliot’s masterpiece, this love is revealed to us as “the unfamiliar Name / Behind the hands that wove / The intolerable shirt of flame / Which human power cannot remove.” And that we may “only live, only suspire / Consumed by either fire or fire.”

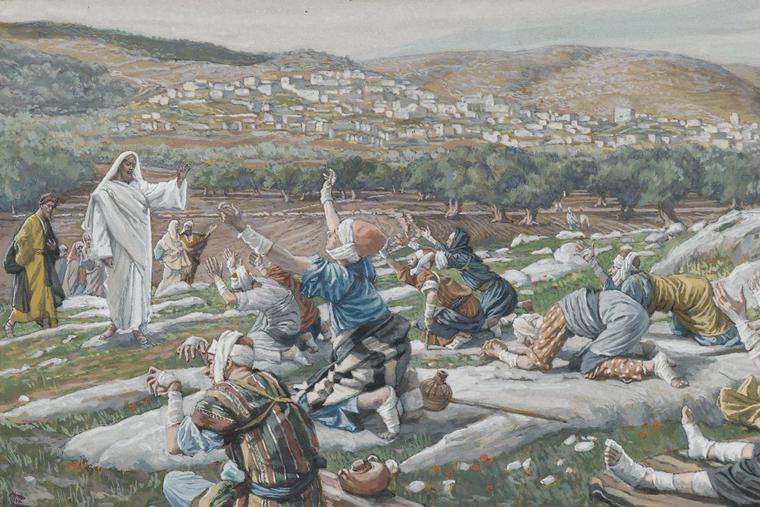

Here, surely, is the best possible gift from God, an experience of himself in the form of love, intended to illumine and warm the soul with a fire blazing forth from his own uncreated love. And it does not finally matter whether we possess this love now, at this moment, however unequal we are in giving thanks for it; or in some future moment we hope to move toward; or even a past moment we remember with gladness, knowing it was real and hoping it may return. That is because what matters most, what we most live for, hope to see and hear, is God himself, bending down from the heights of Heaven, leaving behind his own home, in order to be with us, to speak our name, to beckon us to come unto him.

- Keywords:

- gratitude

- spiritual life