Recruiting Fishers of Men

Maybe the Apostles were having a bad day fishing for fish — but it turned into a good day for “fishing for men.”

Somewhat unusually, this Sunday’s Gospel essentially repeats the theme of last Sunday’s: the call of the Apostles Peter and Andrew.

Last week, the Gospel came from John. This week, in keeping with Lectionary Year B, the same episode is recounted from Mark. Some details are different, and we’ll note them. But, more importantly, the calling of disciples and Apostles remains central. Jesus was not about numbers. He was not interested in multiplying followers for the sake of crowds but in inviting people to follow and bear witness to him and of leaving behind an Apostolic college to maintain the integrity of that witness. Testifying to one’s faith throughout one’s life, privately and publicly, is therefore not some optional extra for some people. It’s an inherent and intrinsic part of every Christian life. We used to make that fundamentally clear in connection with Confirmation, but it is first and foremost a responsibility that flows from our Baptismal dignity.

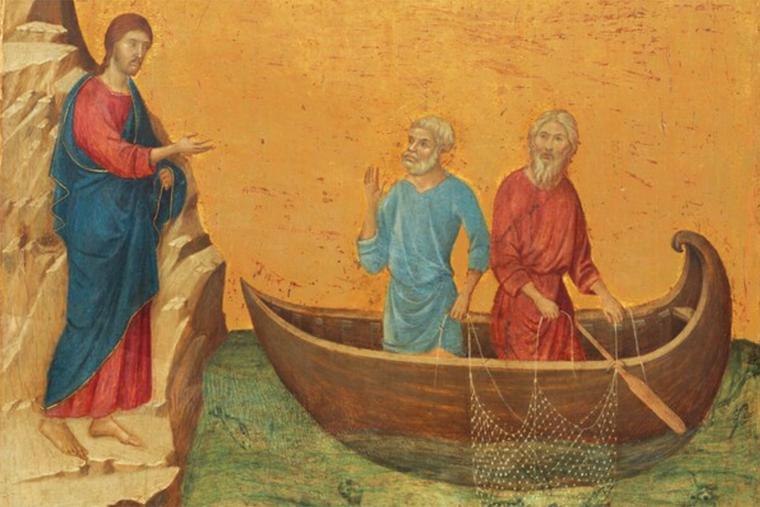

For this week’s exploration of the Gospel in art, we’ll stick to another “Italian” artist (again fully aware that the term is anachronistic, because there will be no “Italy” until 1870): Duccio Di Buoninsegna (c. 1255-c. 1319).

Duccio captures the moment of the calling of those two Apostles in its Marcan depiction. His “Calling of the Apostles Peter and Andrew,” dates from 1308-11, roughly 275 years prior to Caravaggio (whose treatment of this theme we examined last week). Duccio worked in Siena, about 140 miles northeast of Rome. The work was once part of a larger piece, the Maestà, which adorned the altar of Siena’s cathedral from Duccio’s day (the early fourteenth century) until 1506. Liturgical redecoration resulted in the work being moved to a side altar and eventually being cut into its individual components (today’s painting is one of them) over 250 years later. That’s too bad, because Duccio’s intact work was a comprehensive treatment of the lives of Christ and Mary that was not intended to be viewed in only in individual isolation. It’s also unfortunate, because the individual pieces are now in at least seven countries, including the United States (and at least in five different states). One theory of what the entire work might have looked like is here. See also here.

The “Calling” is clearly a piece of medieval art. The artist is not interested in natural scenery but in a theological message (which is why the gold background – we are in a heavenly, not an earthly realm). That said, as the National Gallery of Art link above points out, the artist does pay attention to the physical, at least to some degree, in the folds of the future Apostles’ garments).

Jesus stands on rock, gesturing to the two brothers in the boat, busy with their trade. One’s attention (Andrew’s?) is already captured by Christ; the other (Peter?) seems to be in a “huh, something going on?” moment. They have something of a catch, while other fish swim in the waters beneath.

Jesus is “the Church’s One Foundation” (to borrow an Anglican hymn) but, as today’s Gospel points out, Jesus already renames Simon “Cephas,” i.e., “Peter” (pierre) — “the rock.” (But we have yet to hear Jesus add that Peter is the “rock on which I will build my Church” — see Matthew 16:18) Peter is to become the Rock where Jesus is already standing. Because it’s not just a rocky shore but an outcropping that rises up, can we also see an allusion to the future Sermon on the Mount?

Duccio’s Peter and Andrew already have fish in their net. That depiction is a little troublesome. Today’s Gospel (John 1:40-42) mentions no nets at all. Mark (1:16) speaks only of their “casting a net into the lake,” which sounds like they might have been starting their day. In Luke’s account of the call of Peter (5:1-11), Jesus encounters him after he’s worked all night in vain and caught nothing but, at Jesus’ command, gleans a catch that practically tears his nets. Later, in the Gospels after the Resurrection (John 21:1-14), Jesus also encounters his fish-poor Apostles who, in response to Christ’s initiative, pull in a catch that practically tests the ability of Peter’s bark to cope with the numbers. (Good thing Peter didn’t “renew” his fleet by downsizing!)

Maybe Peter was beginning his day. Maybe he was having a bad day fishing for fish (which turned into a good day in terms of his future career of “fishing for men”). Maybe, since Duccio’s scene is theological rather than purely natural, we can also attach our own theological interpretation.

Peter and Andrew were fishermen, so presumably they were practiced in that art. They might have caught some fish on their own but, as we see from beneath the boat, there’s “a lot more fish in the sea.” Duccio’s Peter and Andrew are “doing what comes naturally,” by their skills. But when nature and grace (represented by Christ) are combined in the future, well — you just might have to replace those nets torn by the bountiful harvest.

If we can draw all these ideas and speculations to one panel of probably at least 65, imagine how rich the whole work is. But it certainly has relevance to us, as disciples, as part of a Church that is apostolic, and depending on God’s grace.

![Fernando Gallego [1440-1507], “St. Andrew and St. Peter” Fernando Gallego [1440-1507], “St. Andrew and St. Peter”](https://publisher-ncreg.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/pb-ncregister/swp/hv9hms/media/2020113015114_a06d506c36c9be311ad5670172fc26e3dd2387502b66b35378f59d88b208535c.jpeg)