Peacocks on Flannery O'Connor's Farm, and in Christian Art

“I intend to stand firm and let the peacocks multiply, for I am sure that, in the end, the last word will be theirs.” — Flannery O’Connor

“You shall know the truth,” said Flannery O'Connor, “and the truth shall make you odd.”

And odd she was. When she died of lupus in August 1964 at the age of 39, Flannery O'Connor had produced two novels and 32 short stories, as well as a number of reviews and commentaries. The novelist, a committed Catholic, left behind in her writing and her personal letters a potpourri of poignant and thoughtful quotes. “Accepting oneself,” she said, “does not preclude an attempt to become better.” In The Habit of Being, a collection of her rambling and deeply personal letters published 25 years after her death, she wrote, “I can, with one eye squinted, take it all as a blessing.”

But the quote that tickled me was this one: “I intend to stand firm and let the peacocks multiply, for I am sure that, in the end, the last word will be theirs.”

At Andalusia, the ancestral farm in Milledgeville, Georgia, where O'Connor lived and wrote, that “last word” must have been quite loud. From childhood, O'Connor had loved birds; and as a young woman she bought a family of peacocks – a peacock, peahen, and four peabiddies – for her farm where, content with their conditions, they bred frequently. According to one estimate, at the time of her death, O'Connor's brood of flying, fluttering, squawking peacocks and peahens numbered more than 100.

I’ve had sort of a peripheral knowledge of O’Connor’s peacocks. I owned a treasured book of her short stories, adorned with a feather. I’ve seen photos of the popular Catholic storyteller sitting casually on her front porch, with peacocks strutting past. But finally, in a book of essays I ordered for inspiration, I stumbled upon her essay “The King of the Birds,” in which she describes the feathered friends who shared her homestead. And wow — all I can say is, wow!

Flannery’s love of birds dated back to when she was only six, when she had a chicken with the unique capability of walking both forward and backward. The story of the talented chicken was picked up in the media, and Flannery became a celebrity for a moment — when she and her talented chicken were featured in a newsreel by the British documentary producer Pathé News.

But her attraction for winged pets didn’t end there. “From that day with the Pathé man,” she wrote, “I began to collect chickens. What had been only a mild interest became a passion, a quest. I had to have more and more chickens. I favored those with one green eye and one orange or with overlong necks and crooked combs. I wanted one with three legs or three wings but nothing in that line turned up.”

Since the young Flannery could sew, she began stitching clothing for chickens. She dressed a gray bantam named Colonel Eggbert in a white piqué coat with a lace collar and two buttons in the back.

She bought still more gussied-up birds: a pen of pheasants, a pen of quail, a flock of turkeys, 17 geese, a tribe of mallard ducks, three Japanese silky bantams, two Polish Crested ones, and several chickens which were a cross between the Polish Crested and the Rhode Island Red.

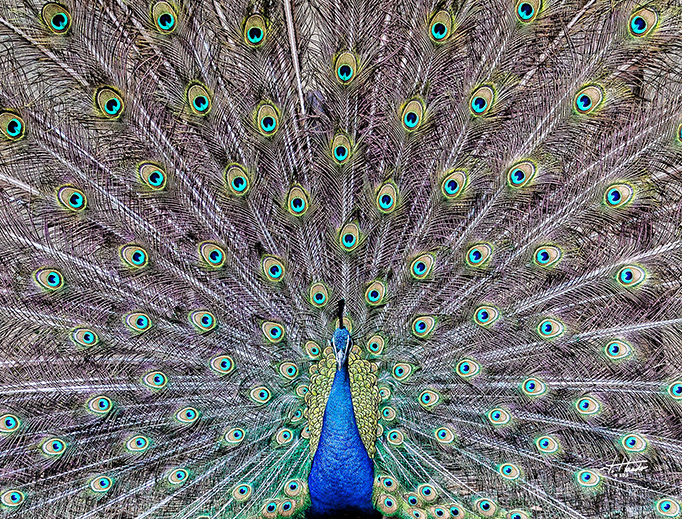

But her avocation culminated, not with fancy chickens, but with peacocks — those elegant fowl who wore their own dress suits, in iridescent blue and green and gold. Flannery saw an ad in the Bulletin for an avian family, and that was a start. With her mother's cautious approval, she ordered the peacock family from Eustis, Florida. “As soon as the birds were out of the crate,” she said, “I sat down on it and began to look at them. I have been looking at them ever since, from one station or another, and always with that same awe as on that first occasion.”

Flannery’s description of her plumed charges’ temperament is matter-of-fact, droll. They wasted no affection toward her, and they ate not only the Startena feed she had purchased, but also the flowers in her mother’s garden. When they weren’t eating the flowers, she wrote, they enjoyed sitting on top of them, and where the peacock sits he will eventually fashion a dusting hole. They were a noisy brood, and the males were given to melancholy squawking.

O’Connor admits that her birds run afoul of others in her neighborhood: her uncle, who planted fig trees only to see the figs decimated by the hungry peacocks; the dairyman, who complained that peacocks had flown into the barn lofts to eat peanuts off peanut hay; the dairyman’s wife, who had found them scavenging among her fresh garden vegetables.

But there’s one other thing about Flannery’s peacocks which intensified all their other unwelcome habits: They reproduced energetically. Peacock sex and peacock nesting and nurturing meant that the six original peacocks multiplied frequently until, when O’Connor told their story in her essay “The King of the Birds,” she owned 40 of the flying, fluttering, squawking peacocks and peahens. By 1964, when she died of lupus at the age of 39, according to some reports her flock had increased to more than a hundred.

The peacock often appears in early Christian paintings and mosaics, where it is a symbol of immortality. The ancient Greeks believed that the flesh of peafowl did not decay after death, and that symbolism was adopted by the early Christians, especially in the Easter season.

* * * * *

I found O’Connor’s story “King of the Birds” in The Norton Book of Personal Essays, a collection of 50 of the finest personal essays of the 20th century, edited and with an introduction by Joseph Epstein. Mark Twain and Bertrand Russell, Shelby Steele and James Baldwin, F. Scott Fitzgerald and George Orwell–these notable writers are among the authors whose essays offer food for thought in The Norton Book of Personal Essays.