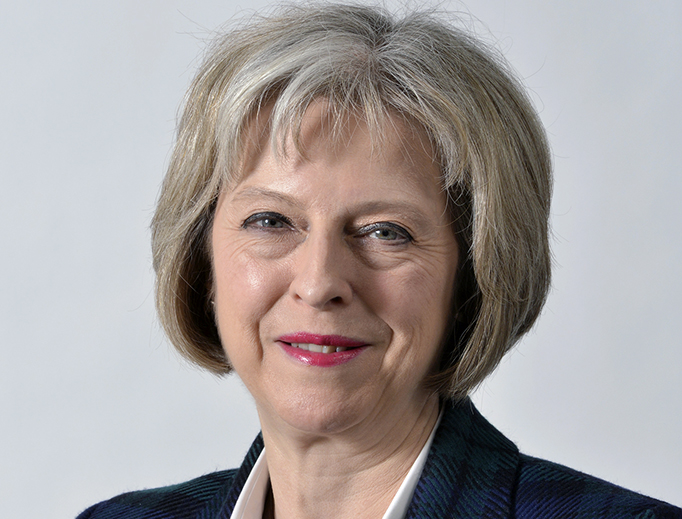

No, Theresa May is Not “Our First Catholic Prime Minister”

Theresa May’s High Church background has prompted some to suggest a strong Catholic influence on her political thinking.

How do UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s religious views shape her politics and policies? As is well known, she is the daughter of a Church of England vicar. Interestingly, in this she is she is following in something of a tradition recent decades: Margaret Thatcher’s father was a Methodist lay preacher and Gordon Brown’s was a Church of Scotland minister.

Mrs. May’s father belonged to the High Church tradition. He was trained at Mirfield in Yorkshire, a college run by the Community of the Resurrection — one of the religious orders established by the Church of England in the 19th century as part of the Tractarian Anglo-Catholic movement, which saw a fostering of Catholic-style worship with an emphasis on weekly Communion services with candles, incense and vestments. This has prompted some – notably Michael Gove, campaigner for Brexit who himself bid for leadership of the Conservative party in the tumultuous days following the nation’s referendum last year – to suggest a strong Catholic influence on her political thinking.

In a recent feature in the Times newspaper, Gove suggested that Mrs. May is Britain’s “first Catholic prime minister” and that her ideas are shaped more by Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum and the Catholic tradition of social justice than by Britain’s “buccaneering” vision of itself as a maritime trading power.

This is probably a step too far. Mrs. May’s version of the Conservative Party is certainly one that associates itself with concern for the poor and marginalised, and she is clearly a woman of faith with a sense of public service. She is a regular churchgoer – as indeed is Michael Gove – and makes no secret of her personal attachment to the Anglican Church. She declared recently that “It’s part of who I am”, and photographs of her walking to Sunday morning service with her husband have appeared in the press.

But her Toryism and her Anglicanism are of a kind that belong very much to the present era rather than to the Catholic social teachings of Leo XIII and St. John Paul II. She famously, as Party Chairman, some years ago warned the party conference that the Tories were in danger of being seen as “the nasty party” through failure to be associated with a more liberal view of society. The issues in focus at that time were not those of poverty or social injustice, but the rather more fashionable ones connected with attitudes to marriage and family. Mrs. May is herself a personal witness to faithful marriage, speaking often of the values she learned from her parents, and has been happily married to her husband Philip for some 30 years. But in her policies she has supported same-sex marriage — voting for the legislation introduced in David Cameron’s government of which she was a member, and speaking enthusiastically of it since.

The Anglo-Catholics in the 20th century — the years in which Mrs. May’s father was being trained and formed – were proud of the tradition of work in city parishes among the poor, and were not associated with the then-establishment of the Anglican Church, which tended to be comfortable with a broadly Tory view of things. Today, that form of Anglo-Catholicism has almost vanished: the churches and convents that they established in, for example, the poor districts of London around The Borough and Southwark are now closed. The 1992 decision of the Church of England General Synod to ordain women as priests split the Anglo-Catholic movement, with some of its main leaders, notably Rev. Geoffrey Kirk, founder of the “Forward in Faith” group, joining the Catholic Church. The establishment in 2011 by Pope Benedict XVI of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham – specifically inviting Anglican clergy to come into full communion with the Catholic Church along with their flocks — brought more Catholics across the Tiber. Remnants of Anglo-Catholicism are now small in number and not effective within Anglicanism, as witnessed by the recent debacle of Rev. Philip North, an Anglo-Catholic nominated as Bishop of Sheffield who was forced to withdraw because of his opposition to women priests. Even though he indicated that he would be happy to work with women clergy, and was known to be supportive of their ministry in general but simply felt unable to ordain any himself, campaigners ensured that he was blocked from taking office.

Mrs. May belongs to the Anglicanism that supports female ordination and likes to see itself as “middle-of-the-road”. It tends to be wary of over-enthusiastic Evangelical activities such as those at Holy Trinity Brompton and its associated “praise songs”, healing ministries and fairly strong messages on matters of sexual morality. The middle-of-the-road approach is friendly in a general sense to ecumenical contacts with the Catholic Church. It can see much to admire in St. John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis, but cannot see any need to affirm doctrine in any very clear sense, or to appear absolutely committed to any moral view except a general one of kindness and neighborliness.

In politics, Mrs. May is patriotic, blending support of free enterprise with social concern. She is committed to the Anglo-American “special relationship”, to NATO, and to the idea of freedom, democracy and human flourishing under the rule of law. Like anyone who grew up in Britain in the second half of the 20th century, she has a profound sense of the idea of Britain as a country defending important values, but is not entirely clear as to what these are. Like many British people, including Michael Gove, she would see Christianity as being linked with that. But unlike him, she would not see the Protestant version of Christianity as being so important, but rather a more generalised and vague sense of values and traditions.

Does this make Mrs. May a “Catholic Prime Minister”? No. It is true to say that the forms of worship she attends might shock some of the Protestant establishment of previous centuries. But probably not nearly so much as the realities of a modern Britain where most people do not go to church at all, where Islam is the fastest-growing religion, and where large numbers of young people – and their parents – do not know the Lord’s Prayer or the basic information on the life, death and resurrection of Christ as told in the Gospels.

It is true to say that probably most practicing Catholics in Britain tend to see Mrs. May as a “safe pair of hands”. The Catholic community itself is not well versed in Catholic social teaching – most have probably no knowledge of Rerum Novarum of Centesimus Annus and if asked about a Catholic view on social issues would only know that the Church is opposed to abortion and to same-sex marriage. They are fairly well able to defend the Church on the first of these, less well on the second where, especially among the young, there is a feeling that the Church is seen as rather harsh. They do have quite a strong sense of Catholic identity, born from an understanding of the years of persecution, and are proud of Catholic schools and of a vague sense of being connected to something worldwide with the pope. They tend to be divided on Brexit. On the whole, they would share Mrs. May’s patriotism and her sense of obligation to the community and the common good.

And they mostly also share, with the rest of the country, a vague sense of sadness at the present moral and spiritual state of the country. And some are praying about that.