Ven. William Gagnon — Missionary of Mercy in the Vietnam War

Brother William’s weapons included a scapular, his rosary and a statue of Our Lady of Fatima.

He had literally worn his heart out.

On Feb. 28, 1972, Brother William Gagnon collapsed and died. His fellow Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God buried him in the garden of their convent and hospital near Saigon, and immediately, people started visiting his grave — the Vietnamese novices he had guided into a stable community, children caught in the crossfire of a post-colonial power struggle, the refugees he had nursed back to health from malnutrition, and the soldiers whose wounds he had cured. In the community of the Hospitallers, those who had known him retold anecdotes of his courage, constant service, and leadership in turmoil. Brother William’s good works outlived him, just as he knew they would.

William Gagnon was born in 1905, the third of 12 children of working-class French Canadians who had immigrated to Dover, New Hampshire. He had a deep faith that showed from early on. When William was 13, the family was returning from church in their horse-drawn carriage. They could see smoke in the distance. William stayed with his younger siblings while is parents and older brothers ran to fight the wildfire.

“Don’t worry,” he told his mother. “I’ll stay here and pray.”

No one was injured, and the fire resulted in uncovered fertile land for agriculture.

In his late teens, William joined his father and his older brothers in working at the cotton mill in town and helping to support the family. But he also had another desire: to be a missionary. He applied to the Marists, but he was rejected when a medical exam discovered he had a kidney condition. A few years later, he read a newspaper column about St. John of God, the sixteenth-century Spaniard who had founded a community of brothers to care for sick. The order intrigued him, and they had missions all over the world. After a visit to the community in Montreal, he entered as a postulant in 1930.

When his father was injured a few months later, family duty called him home temporarily. There were still too many young mouths to feed in the Gagnon household, so he stepped up to help during his dad’s convalescence.

When his father recovered, William returned to Montreal in 1931 and finished his novitiate. He spent the next 20 years working in the order’s hospitals in Canada, as well as serving as provincial in Montreal. His time in Montreal ended in a forced midterm resignation without just cause. He submitted quietly and signed without question the prepared resignation letter handed to him. Brother William just asked to be transferred out of the city to avoid rumors.

At his new assignment he confided to another brother his humiliation and that he was working through it by prayer and meditation. Then, he volunteered to go to Vietnam, the fulfillment of a long-held desire to be a missionary. With his inherited French, he could manage the logistics of starting a new community in the unraveling French colony.

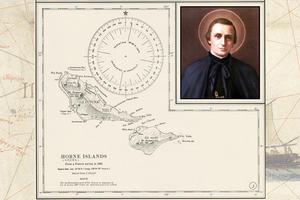

Brother William and his fellow Canadian brothers landed in Vietnam in 1952 in the middle of the Indochina war. The French were trying to maintain a vestige of power against communist forces bearing down from the north. The brothers established a hospital in the war-torn conditions they would work in for the next two decades. They could hear grenades land on the roof and roll off into the grass, guns firing and bombs exploding, sometimes in the distance, sometimes close to home. Brother William placed a statue of Our Lady of Fatima outside the house in the direction of the fighting as protection. Along with his daily prayers to Mary, it worked. When a bomb blew the roof off the hospital, no one was even injured.

The brothers cared for everyone, civilian and soldier, regardless of whom they fought for, but they weren’t always repaid with kindness. After one man recovered from a serious illness through the brothers’ care, he showed their picture to the guerillas. No one knows how he got the picture, but the man’s action posed a serious threat to the brothers, from arrest to death. They knew of other priests who had been less careful and died. At the request of the bishop, they left the mission for a few days until the danger had passed. But Brother William’s resolve never wavered.

"All of us, we remain religious missionaries and work only for the poor, regardless of what is happening around us,” Brother William wrote to his superiors in Canada.

The conflict in the north was creating a stream of refugees flowing south. The brothers moved south, too. The mission in Bien-Hoa, near Saigon, would become the Vietnamese province of the Brothers Hospitallers and the center of Brother Williams’ work.

He wore many hats — provincial, nurse, general contractor, novice master, fundraiser, and social worker. Brother William had been made provincial of the mission with good reason. He was an excellent organizer and spiritual leader. He led with practicality, simplicity, and humility. He took on the simplest and least desirable tasks — holding a patient’s hands, preparing bodies for burial, buying food in the market, serving soup to the tuberculosis patients. He guided the construction of the new hospital, too, including the logistics of getting materials and labor. He joined in the work, too, of making the bricks from sand and water.

He salvaged equipment from the American military as well. Embittered soldiers laughed at him and his brothers hauling away old office furniture for the hospital. He smiled back. He had the faith and hope to build knowing a bomb could soon destroy everything.

William’s strength and peace came from his prayer. The rosary beads slipped through his fingers under his scapular in spare moments. At night he knelt before the cross in his cell contemplating the absurd death of Jesus that had nevertheless ended in the Resurrection. In caring for the sick and suffering, he was united with Christ in reparation for the sins of the world. William had been made provincial of the mission for a reason. He was an excellent organizer and spiritual leader, but he considered himself the least of the Hospitallers, most useful in humble tasks and not caught up in the complexities of politics and war theory. He was there to serve Christ in the sick. His leadership and decisions through 20 years of danger and war were guided by his contemplation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Where else could he find anything to make sense of the suffering of the innocent people who came to the hospital every day? The scenes could be heart wrenching. Thousands of people trying to escape the horrors of war sought medical care, rest, and food at the hospital. Refugees arrived malnourished and exhausted from long marches, perhaps with injuries that hadn’t been cured and usually with children.

Sometimes there was little that could be done with the few resources they had. Brother William cleared a table so two other brothers could attempt an emergency procedure on a woman with a young child. While the nurses brought the woman to the table, Brother William picked the child up, reassured her mother would be all right, and placed the little one with others outside the room. Then he returned to help. The woman asked for baptism and Brother William poured the water. That was all he could do. The woman was already gasping the death rattle. This time, he could only bring the child her mother’s body. He walked out of the hospital and cried out to God — for the woman and the child, and for peace.

At night, he walked to the chapel under the light of exploding artillery and the background noise of bombs — “the concert,” as he called it. Again, he prayed for peace, for the deceased, and for the protection of refugees. He was also a peacemaker among his fellow brothers, a diplomatic intermediary armed with prayer. He wanted peace in his community and in each of his brothers. If he heard backbiting or arguing, he redoubled his prayers to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. He was also attuned to those around him and knew how to show compassion to each one. One day he noticed one young missionary brother was especially down. Brother William suspected he was homesick, especially as his relationship with his father had become distant. Brother William encouraged him to write home and reached out himself to the man’s uncle, who was one of the Brothers Hospitallers in Canada. Slowly but surely, and even from afar, father and son reconciled.

The conflict and fighting only moved southward through the sixties. As their work became more dangerous than ever, the brother’s also started to believe that he had a gifted intuition. On Feb. 1, 1968, seven thousand refugees descended on the hospital grounds. The Lunar New Year was about to start and various rumors began to fly. Some said there would be a temporary cease-fire to celebrate the holiday. Others had heard that a brutal attack was in store. Brother William had no idea what would happen, but he knew that without resources to care for so many people, proper hygiene would be impossible leading to the spread of disease, Brother William told them all to disperse.

The next night, the hospital grounds were bombed in the bombardment of Saigon. Those who had refused to leave were killed. Months later, with the fighting no better and the day exceptionally hot, Brother William exempted the community from gathering in the community room for the usual hour of recreation. Had they all been there, they would have become victims of the bomb that hit the community room. Another night, Brother William`s own peace of heart would save him. The fighting around them was intense and bullets were hitting the convent. Brother William had always counseled the community to try to sleep through the night and trust that their time on earth was in God’s hands. That night, though, with bullets hitting the convent itself, the brothers couldn’t sleep, and they went to wake their provincial.

“What’s the matter?” Brother William asked, standing in the doorway of his room.

One of the other brothers jumped on Brother William and pushed him back. A bullet whizzed by them and exploded in the doorframe where Brother William had been standing. Brother William got up and sent everyone back to their cells to sleep.

From the beginning, The Hospitallers had also collaborated closely with the Redemptorist Fathers. The brothers made retreats with the priests and also accompanied them into the jungle. Leaving the city, they went to the two of the many tribes in Vietnam to dispense medicines and the sacraments. Brother William was also deeply impressed by his visit to the leper colony run by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul.

After 1970, Brother William’s health started to decline. He gave his last months to the mission by doing the simple tasks he had the strength for in the dispensary and apologizing to the community for being a burden. When he died, he was laid out on a bed of tea leaves and a white sheet, and the people he had served insisted on providing him a teak wood coffin. He was buried near the chapel. Today, ex-votos, the testimony of those who claim to have received favors through his intercession, decorate his grave.

As he had once said, “All worldly honors are nothing but the smoke and fire of burning straw. All that remains is the little good that we have done, if we have managed to make the most of the grace which our good Lord has given us at every instant in our lives.”

Brother William had formed the Vietnamese novices who joined the Canadian brothers into a solid foundation to continue the work of the Hospitallers into the future. The mission survived the fall of South Vietnam to the communist Viet Mihn and still continues to this day.

He never looked for recognition, but his life of heroic dedication to the sick and poor won him the title venerable in 2015. His cause for canonization seeks to find a verified case of an instantaneous, complete and lasting miraculous cure from a serious condition through his singular intercession before he can move along to the next step in the sainthood process and be beatified.

- Keywords:

- missionaries

- vietnam