Chesterton's “The Flying Inn”: A Comedic Window Into Contemporary Culture

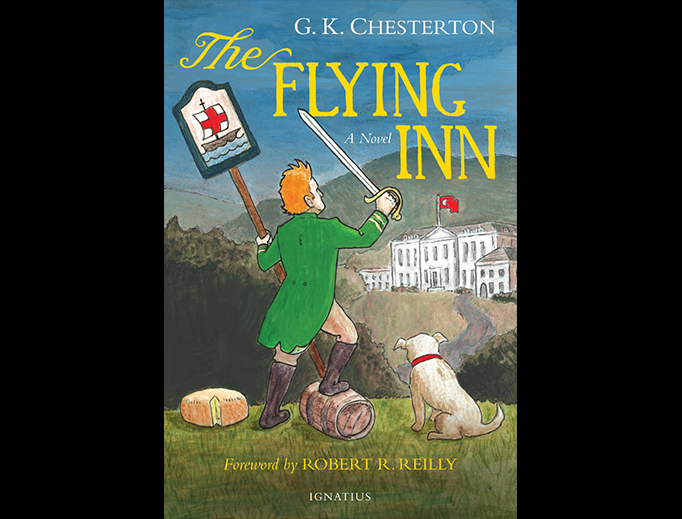

Ignatius Press has just re-released this rollicking tale with a new Foreword by Robert R. Reilly.

I've been traveling – and I love a good novel on a road trip! Sentences rich in imagery and imagination inspire me to abandon my usual fare of sober nonfiction, of politics and spirituality and history, for a week or two and bask in the creative juices, peeling back the corner of an adventure or a mystery to peek at its darker truths.

There are a few contemporary Catholic writers whose droll descriptions of absurd reality capture my Catholic imagination: Dean Koontz, slipping a pro-life message into an improbable mystery best-seller. Brian Doyle, spinning yarns about family life and small-town faith.

But my favorite classical writer is G.K. Chesterton, whose expertise in apologetics (Orthodoxy, The Everlasting Man) is matched by his storytelling prowess (Father Brown Mysteries and The Man Who Was Thursday). Still, I'd never heard of Chesterton's final novel The Flying Inn – and so I was delighted to hear that Ignatius Press has just re-released this rollicking tale with a new Foreword by Robert R. Reilly.

In The Flying Inn, a form of “progressive” Islam has imposed severe restrictions on the sale of alcohol throughout the country, causing pub owner Humphrey Pump and liquor lover Captain Patrick Dalroy to roam the English countryside in their cart with a barrel of rum in an attempt to evade Prohibition. The pair skillfully exploit loopholes in the law to temporarily prevent the police – including an Islamic military force – from taking action against them.

The Flying Inn can be enjoyed on many levels. First, the exquisite prose! Chesterton's most raucous political fantasy might revolve around a keg of rum, but it begins like this:

“The sea was a pale elvin green and the afternoon had already felt the fairy touch of evening, as a young woman with dark hair, dressed in a crinkly copper-coloured sort of dress of the artistic order, was walking rather listlessly along the parade of Pebblewick-on-Sea, trailing a parasol and looking out upon the sea's horizon.”

The imagery is so intense, the circumstances so absurd, the characters so eccentric, that the reader can enjoy Chesterton's work at that visceral level. But there's much more, as Reilly points out:

“Chesterton uses the fantastical to reveal the real, and never has he done so in as prescient a way as in The Flying Inn. In fact, there is nothing too absurd in this satirical work for it not to have actually taken place actually.”

As evidence, Reilly cites numerous examples of contemporary British society's deference to Islam, despite that nation's majority Christian population. There are, Reilly reports, sharia courts operating in Britain; a KFC refused to permit a customer to use a hand wipe because it was saturated with alcohol, which is expressly prohibited in the Qur'an; a Muslim checkout worker in Britain refused to sell ham and wine to a non-Muslim customer because it was Ramadan. “All of these,” Reilly says, “could have come straight out of The Flying Inn – from fiction then to fact today.”

The remorseful chauffeur; the sensible little High Church curate; the futurist “watchers for the Dawn”.... these and other characters tumble through what Dale Ahlquist, president of the American Chesterton Society, called “a joyous romp of mirth and mayhem.”

But on a more serious level The Flying Inn, in Reilly's words, “lays bare the corrupt mindset that subverts Western civilization in favor of a future beyond. So grab a cask of rum and draw your sword.” It's a good read.