Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI Reflects on the Last Things

In an extract from his latest book-interview, 'Last Testament', Benedict XVI reflects on death, God's judgment, and the afterlife.

As the Church enters the liturgical season of Advent, a time of expectation and anticipation of Christ’s return in glory, it’s perhaps timely to publish here for the first time Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI's recent thoughts on the Last Things.

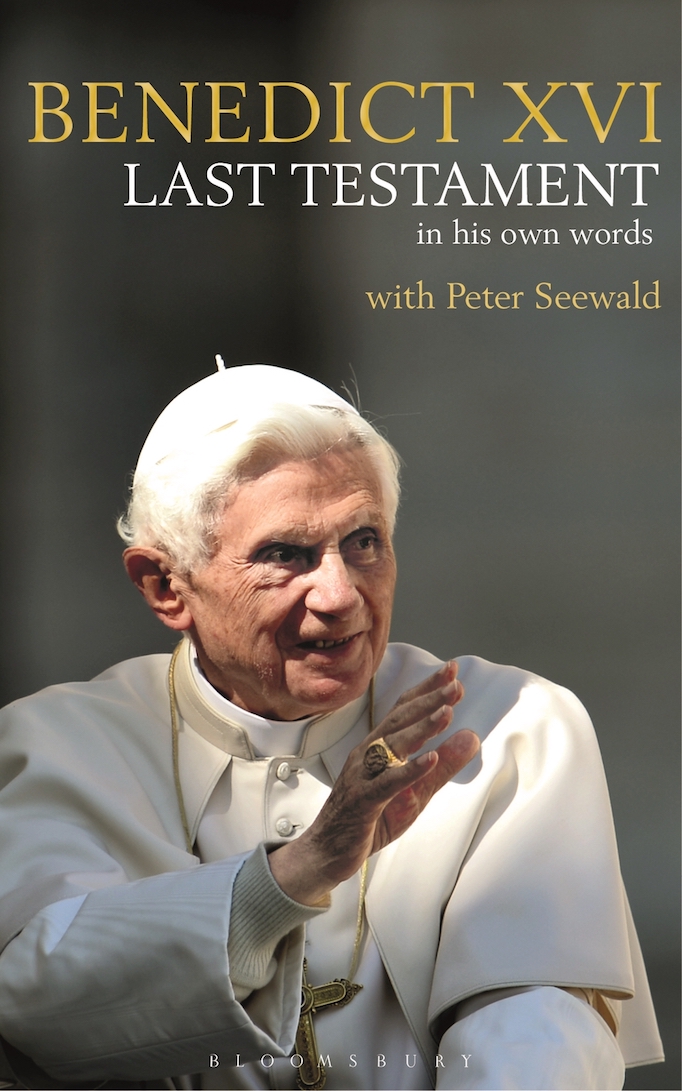

In this extract from the new book, Last Testament – In His Own Words — Pope Benedict XVI With Peter Seewald, the Pope Emeritus discusses his approach to death, judgment and how close he feels to Jesus as he reaches the end of his earthly life.

He also reflects on the “dark night” of the soul, dealing with the problem of evil, and his expectations of the life to come.

PETER SEEWALD: The central point of your reflections was always the personal encounter with Christ. How is that now? How close have you come to Jesus?

Is this connected to a loss of God’s nearness? Or with doubt?

Not doubt, but one feels how far one is removed from the greatness of the mystery. Of course new insights are opened up again and again. I find this touching and comforting. But one also notices that the depths of the Word are never fully plumbed. And some words of wrath, of rejection, of the threat of judgment, certainly become more mysterious and grave and awesome than before.

One imagines that the Pope, the representative of Christ on earth, must have a particularly close, intimate relationship to the Lord.

Yes, it should be that way, and I did not have the feeling that he was far away. I am always able to speak with him inwardly. But I am nevertheless just a lowly little man who does not always reach all the way up to him.

Do you experience the ‘dark nights’ of which the saints speak?

Not as intensely. Maybe because I am not holy enough to get so deep into the darkness. But when things just happen in the sphere of human events, where one says: ‘How can the loving God permit that?’, the questions are certainly very big questions. Then one must maintain firmly, in faith, that He knows better.

Have these ‘dark nights’ existed in your life at all?

Let’s say they’ve not darkened the whole, but the difficulty so often with God is the question of why there’s so much evil and so forth; how something can be reconciled with His almighty power, with His goodness, and this certainly assails faith in different situations time and again.

How does one deal with such problems of faith?

Primarily by the fact that I do not let go of the foundational certainty of faith, because I stand in it, so to speak, but also because I know if I do not understand something that doesn’t mean that it is wrong, but that I am too small for it. With many things it has been like this: I gradually grew to see it this way. More and more it is a gift; you suddenly see something which was not perceptible before. You realize that you must be humble, you must wait when you can’t enter into a passage of the scriptures, until the Lord opens it up for you.

And does He open it up?

Not always. But the fact that such moments of realization happen signifies something great for me in itself.

Does a Papa emeritus fear death? Or fear dying at least?

In a certain respect, yes. For one thing there is the fear that one is imposing on people through a long period of disability. I would find that very distressing. My father always had a fear of death too; it has endured with me, but lessened. Another thing is that, despite all the confidence I have that the loving God cannot forsake me, the closer you come to his face, the more intensely you feel how much you have done wrong. In this respect the burden of guilt always weighs on someone, but the basic trust is of course always there.

What bears heavily on you?

Well, that you have not done enough for people, not treated people rightly. Oh, there are so many details, not very significant things – thanks be to God – but just so many things where you have to say that something could and should have been done better.

So when you stand before the Almighty, what will you say to him?

I will plead with him to show leniency towards my wretchedness.

The believer trusts that ‘eternal life’ is a life fulfilled.

Definitely! Then he is truly at home.

What are you expecting?

There are various dimensions. Some are more theological. St Augustine says something which is a great thought and a great comfort here. He interprets the passage from the Psalms ‘seek his face always’ as saying: this applies ‘for ever’; to all eternity. God is so great that we never finish our searching. He is always new. With God there is perpetual, unending encounter, with new discoveries and new joy. Such things are theological matters. At the same time, in an entirely human perspective, I look forward to being reunited with my parents, my siblings, my friends, and I imagine it will be as lovely as it was at our family home.

Eschatology, the doctrine of the ‘last things’ – death, purgatory, the dawn of a new world – is one of the fundamental themes of your work, what the book you consider your best is about. Are you able to profit from your theology today, when you personally stand immediately before these eschatological questions?

Indeed, especially what I considered about purgatory, about the nature of pain, the meaning it has, and also about the communal character of beatitude. I think about these because it is very important to me to believe that one is immersed in a great ocean of joy and love, so to speak.

Do you consider yourself one of the enlightened?

No I don’t! [Laughs] No.

But is enlightenment, next to holiness, not also a definite goal of the Catholic life in Christ?

Now, the concept ‘enlightened’ has something a little elitist about it. I am an entirely average Christian. Naturally Christianity is about a concern to recognize the truth, which is light. By virtue of faith a simple man is enlightened, because he sees what others, who are so clever, cannot perceive. In this sense, faith is enlightenment. Baptism in Greek means a photism, an enlightenment, a coming into the light, becoming one who sees. My eyes are then opened. I see this dimension which is wholly other, something it is not possible for me to perceive with the eyes of the body alone.

This extract has been published by kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Last Testament – In His Own Words — Pope Benedict XVI With Peter Seewald is available from Bloomsbury priced at $24.00

Photo: Peter Seewald and Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in conversation (L'Osservatore Romano).

- Keywords:

- benedict xvi

- eschatology

- judgment

- last things

- peter seewald