Newman the Novelist: His Prolific Pen Highlights His Holy Life

John Henry Newman’s literary output is remarkable.

A Portrait in Style

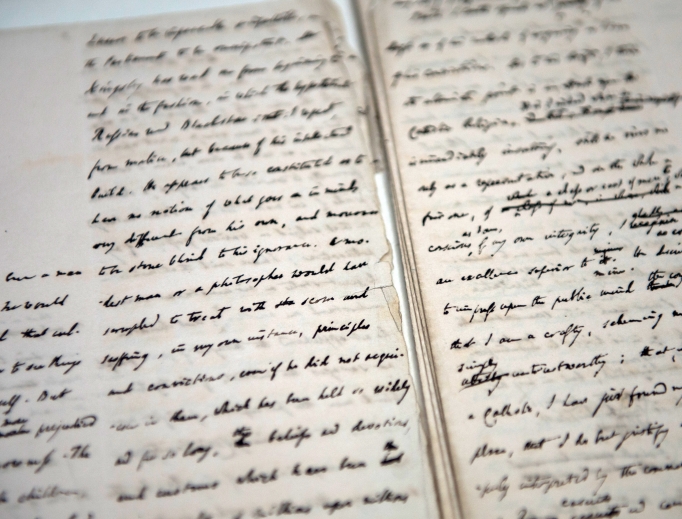

“As a writer of English prose Newman stands for the perfect embodiment of Oxford, deriving from Cicero the lucid and leisurely art of exposition, from the Greek tragedians a thoughtful refinement, from the Fathers a preference for personal above scientific teaching, from Shakespeare, Hooker, and that older school the use of idiom at its best.”

So said the Catholic Encyclopaedia (1913). Perhaps this verdict on John Henry Newman as a writer is to be expected from such a source. A less expected validation comes in James Joyce’s autobiographical novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). Joyce’s fictional persona Stephen Dedalus declares that the greatest writers in English are Lord Byron and Newman.

Incredibly, this really was the view of the lapsed Catholic Joyce. And yet no residue of Joyce’s Catholic upbringing seems to have influenced his view of the late cardinal’s prose style, for Joyce had no time for the ancient faith of his ancestors; he died in 1941 unreconciled to the Church.

Joyce is often seen as one of the fathers of literary modernism, partly shaped by the carnage of the Great War and its political, social and economic aftermath. His 1922 novel Ulysses is often cited as a key text in this literary movement, as well as being, for decades, a book banned for obscenity in both England and Ireland.

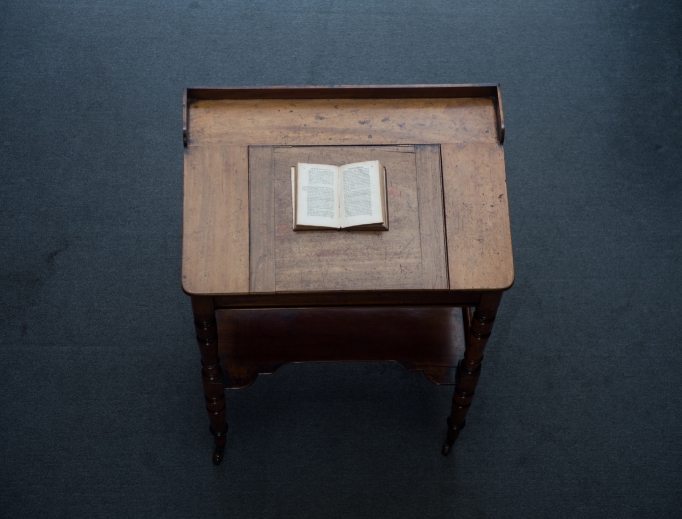

However, there was a link to Newman in Joyce’s intellectual formation. The Irishman had studied modern languages at Dublin’s University College, the successor of Newman’s failed attempt to establish, at the request of the Irish bishops, a Catholic university in that city.

Newman’s Novels

Whereas Newman’s more clearly theological works are to be expected, there are few saints with not one but two novels to their name. And like his later novelist-admirer, James Joyce, Newman’s fiction was very much of its time.

Speaking to the Register, Joseph Pearce, author and director of book publishing at the Augustine Institute, said, “Newman’s novels are superbly well-written, but they are vehicles for the discussion of ideas, heavy on gravitas and light on levitas. As such, they are certainly not light reading and are not for those seeking action-packed page-turners.” The novels are, instead, he added, “powerful conveyers of the drama and passion of the interior life ... muscular engagements with the inextricable relationship between faith and reason.”

Newman’s first novel, Loss and Gain, was published in 1848. He was bold in entering the fray with a novel at that time. That same year such classics as Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens, William Thackeray’s Vanity Fair and Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall were all published. Loss and Gain is largely autobiographical, set in Oxford and detailing the trials, tribulations and triumphs of a Catholic convert from Anglicanism. It is hardly surprising that the novel received mixed reviews — largely, it seems, on denominational grounds. Nevertheless, it generated immense interest and went through nine editions in Britain alone during Newman’s lifetime. Pearce posits, “In choosing to use the medium of the novel to convey a quasi-autobiographical account of his own conversion in Loss and Gain, Newman was very much in tune with what might be called popular culture at the time, the novel being in vogue and in the aesthetic ascendant in early Victorian England.”

It is interesting to note that, a year after the novel was published, when Newman delivered his “Lectures on Certain Difficulties Felt by Anglicans in Submitting to the Catholic Church” at the London Oratory, sitting in the congregation listening were Thackeray and Anne Brontë’s sister, fellow novelist Charlotte.

Newman’s Novels: Part II

One novel, as anyone who has attempted to write one knows, is an achievement; but Newman wrote two. In the summer of 1855 Callista, a Tale of the Third Century appeared. A historical novel set in third-century North Africa, it tells the story of early Christians living through Roman persecution and of the conversion of a girl named Callista.

Callista, too, went through numerous editions — eight in total — by the time of the author’s death in 1890. Callista was published the same year as Westward Ho! by Charles Kingsley, with whom Newman would famously lock horns in debate some years later, ultimately resulting in Newman’s most famous work, the autobiographical Apologia Pro Vita Su (1864).

Speaking to the Register, best-selling Ignatius Press author Michael O’Brien sees a timely relevance in this novel about a hostile state persecuting believers. “Callista is a stark portrait of both believers and nonbelievers during a persecution in third-century Roman North Africa,” O’Brien said. “It is a timeless classic, and in our own darkening age, it may prove to be a source of wisdom for those who follow Jesus wholeheartedly.”

In that regard Callista’s words on conscience are particularly interesting, especially given what Newman was to write later on the subject: “You may tell me that this dictate is a mere law of my nature, as is to joy or grieve. I cannot understand this. No, it is an echo of a person speaking to me. Nothing shall persuade me that it does not ultimately proceed from a person external to me. It carries with it the proof of its divine origin. My nature feels towards it as towards a person. When I obey it, I feel a satisfaction; when I disobey, a soreness — just like that I feel in pleasing or offending some revered friend. The echo implies a voice, a speaker. That speaker I love and fear.”

Literary Impact

There are many significances to Newman’s canonization coming as it does at this time in the history of the Church. He was an exemplary priest and pastor, working with the poor of Birmingham, and explaining, and tirelessly defending, the mystery of the Church, its teachings and divine foundations. He is thus a model for today’s clergy, particularly so, perhaps, for bishops and the College of Cardinals. He was also a supremely gifted and hardworking intellectual at a time when the intellectual high ground was being hijacked by a triumphant secular and materialist culture, whether in the so-called “higher criticism” of 19th-century biblical research or in the promotion of new scientific and economic theories such as those in Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (1859).

Perhaps what is most surprising is that Newman embraced the most popular art form of the time, namely the novel.

So what do 21st-century Catholic novelists make of this new saint and his fiction? “Newman’s canonization is that of a man of extraordinary fidelity, on every level of his being, reinforcing the Catholic understanding that the whole man is called to become the ‘new man in Christ,’” O’Brien said. “Newman’s mind, his spirituality, his holiness includes the life of his imagination — the ‘baptized imagination,’” he added. O’Brien feels that there is “abundant evidence for this to be found in the beauty of all Newman’s writings and in his fiction.”

Award-winning, U.K.-based Catholic novelist Fiorella De Maria told the Register: “There is a strong significance [in Newman’s canonization] for Catholic artists particularly at this time. I believe that we are on the cusp of a much-overdue Catholic literary revival, and I do not believe it is a coincidence that a man who was so instrumental in the Catholic revival of the 19th century should be canonized at this moment.” She added, “It is a very exciting moment for British Catholics more generally, but also for Catholic writers.”

Catholic Revival?

Her sentiments are echoed by Pierpaolo Finaldi, CEO of the London-based Catholic Truth Society, publishers to the Holy See and one of Newman’s original publishers, who told the Register, “The variety of the saints is truly astonishing and is proof of the inexhaustible richness of our faith. … For England, especially in the last century, Catholicism has so often gone hand in hand specifically with literary genius. One need only mention Waugh, Greene, Chesterton and Tolkien, to name but a few. Why is that? Perhaps the destruction of our material artistic heritage during the Reformation has meant that literature and music are all that we had to fall back on.”

Finaldi sees in Newman’s canonization the seeds of a literary “Second Spring.”

“The death of art is to be found in the fawning search for acceptance by the establishment,” he said. “Newman never received that acceptance, but his recognition is really only just beginning. If there is to be a Catholic literary revival, writers and artists will need to pit themselves against the world around them as Newman did; but if sanctity is the reward, then I say: Bring it on.”

What is being declared at St. Peter’s on Oct. 13, 2019, of course, is not the merits of literary talent per se, but the model of heroic holiness. As Pearce makes clear, “Newman is not being canonized as a novelist or even, in a broader sense, as a writer.” Nevertheless, he says, “It is indeed astonishing that someone so gifted in these areas should also be one of the finest literary figures to emerge in an age which could be considered a Golden Age in literature. It is surely fitting that one with such heavenly [literary] gifts should have attained the gift of heaven.”

K.V. Turley writes from London.