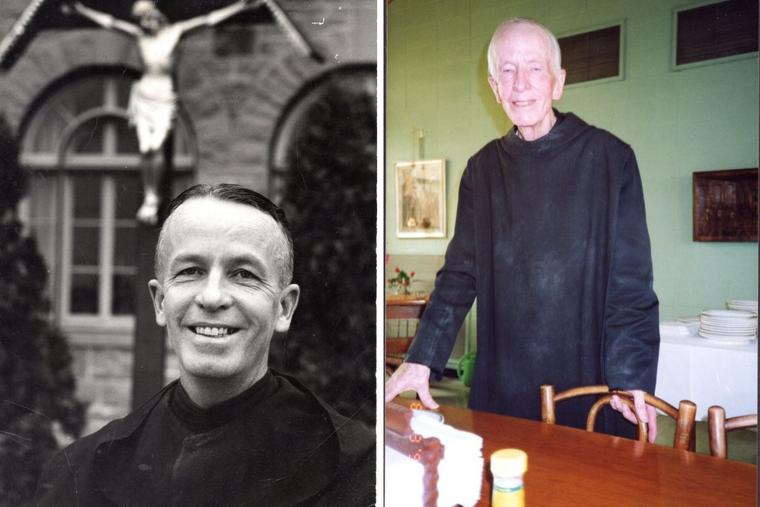

Heroic Mariner-Monk Sails for Sainthood: Servant of God Marinus LaRue

The U.S. bishops voted in June to advance Servant of God Marinus LaRue’s canonization cause.

For the longest time, Benedictine monks at St. Paul Benedictine Abbey in Newton, New Jersey, did not know modest Brother Marinus LaRue, their dishwasher, bell ringer and gift-shop worker, had been a U.S. Merchant Marine captain. During the Korean War, Leonard LaRue headed what became — and remains — the largest humanitarian rescue operation by a single vessel in history, whether during war or civilian conditions. In a single trip, he evacuated 14,000 refugees to safety in a freighter designed to carry 47 officers and only 12 passengers, along with the cargo.

When fellow monks eventually discovered he was responsible for what was called “The Christmas Miracle,” Brother Marinus humbly preferred not to talk about the details. Now, many will learn of the unmatched effort he directed, as his canonization cause has been advanced.

At the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ June 16-18 assembly, 99% of the bishops voted to advance the canonization cause of Servant of God Brother Marinus. Bishop Arthur Serratelli of Paterson, New Jersey, opened his cause in 2019.

A Life of Service

The heroic story starts in December 1950. The week before Christmas, Capt. LaRue, commander of the SS Meredith Victory, a ship originally built to carry war supplies in World War II, was heading into the harbor of Hungnam, North Korea, with 300 tons of jet fuel and military supplies. The Korean War had started six months earlier.

On Dec. 22 he saw a scene bordering on the chaotic, later likening it to something from Dante’s Inferno. At Hungnam, 100,000 troops were awaiting a Dunkirk-like evacuation. The U.N. and U.S. forces had retreated to this city nearly 140 miles north of the 38th parallel, the official demarcation between North and South Korea.

As ships were loading the men and all their military equipment aboard, and the Army and naval vessels and carriers were shelling the North Korean and Chinese Communist troops to stop their entry into the city, nearly 100,000 Korean refugees stood on the shore, in the snow and freezing cold. Frightened men, women and children were hoping for help as they fled certain death.

Looking through his binoculars as his ship approached, LaRue later remembered, “Refugees thronged the docks. With them was everything they could wheel, carry or drag. Beside them, like frightened chicks, were their children.”

When some Army colonels boarded and asked if he were willing to take some refugees aboard for this dangerous mission, he immediately unloaded all military cargo and supplies, except for the jet fuel, and started to board the refugees using platforms on the ship’s booms and an improvised gangplank.

Getting the Korean refugees aboard took continuous work through the night into the next day, Dec. 23. With not a space left in the ship’s five cargo holds or up on the main deck, Capt. LaRue and his crew miraculously managed to pack 14,000 Korean refugees aboard a 455-foot cargo freighter built to hold its crew and only a dozen passengers. Amid the continuous explosions and artillery fire from both sides, the ship was one of the very last to leave the harbor, as the military was blowing up any remaining equipment plus all port facilities.

“Finally, as the sun rode high the next morning, we had 14,000 human beings jammed aboard,” Capt. LaRue would recall. “It was impossible, and yet they were there.”

He had the SS Meredith Victory well on its way to later being named the “Ship of Miracles.” Yet he faced a number of trials as the ship steamed out of Hungnam’s harbor. There was little to no food and water for the refugees — and no heat in the freezing cold and neither sanitary facilities nor medicine. The refugees knew no English, and the crew knew no Korean. And the ship was still loaded with volatile jet fuel while the harbor was heavily mined. Communist submarines were prowling the waters. LaRue had to steer the SS Meredith Victory through this maze without an escort or defense 450 sea miles southeast to Pusan (today called Busan).

The ship arrived on Dec. 24 but was turned away because Pusan was already overflowing with military personnel and refugees. Capt. LaRue was able to obtain a small amount of food and water for those on deck, but then had to travel more than 40 miles southwest to Geoje Island, arriving on Christmas Eve; the ship had to wait at sea until the next day to get the refugees from the ship to shore via LST landing crafts.

All 14,005 of them reached shore safely — five more were added to their ranks, as babies were born on deck during that trip. Everyone, from youngest to oldest, miraculously survived. And no one was injured, despite the conditions. It was a reminder of St. Paul’s frightening sea journey during which he told the crew and passengers none would be harmed but all would arrive safely on shore of Malta.

“The mission — undertaken against all odds — has been called a ‘Christmas Miracle’ by historians,” recounts the Benedictine’s website, OSB.org. The Korean War Military Foundation, in its remembrance of the event, proclaimed, “Under Capt. Leonard LaRue, the Meredith Victory performed the largest humanitarian rescue operation by a single ship in history.” The U.S. Dept. of Transportation Maritime Administration later hailed it as “one of the greatest marine rescues in the history of the world.”

A Life of Prayer

The fanfare, which came later, did not affect Capt. LaRue, who remained in command of the Meredith Victory until 1952, when the ship was decommissioned.

Inspired by contacts with Benedictine monks during his travels, he answered a religious vocation and in 1954 entered St. Paul Benedictine Abbey in New Jersey to become a Benedictine monk and live a quiet, simple life of prayer. He selected the name Brother Marinus. Although the name might have echoes of his two decades at sea, he took it in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary. He continued as a modest brother, happily doing menial tasks, until his death on Oct. 14, 2001, at age 87.

“I think often of that voyage. I think of how such a small vessel was able to hold so many persons and surmount endless perils without harm to a soul. And as I think, the clear, unmistakable message comes to me that on that Christmastide, in the bleak and bitter waters off the shore of Korea, God’s own hand was at the helm of my ship,” Brother Marinus said while reflecting on the mission and his vocation, as reported in The Beacon, the newspaper of the Paterson Diocese. The same source added the simple reason Brother Marinus gave for mustering the courage to lead that treacherous and daring rescue. He said, “The answer is in the Holy Bible — ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’”

At Brother Marinus’ funeral, in his homily Benedictine Abbot Joel Macul said that the monk “left the sea with all its drama and heroic opportunities for the intimacy of a daily sustained relationship with the Lord and his Mother.”

In a letter two years before opening the cause for Brother Marinus, Bishop Serratelli wrote, “The heroic account of Capt. LaRue saving 14,000 Korean refugees under such perilous conditions is most impressive. That the ship, the SS Meredith Victory, has been called the ‘Ship of Miracles’ is truly appropriate.” He appointed Father Pawel Tomczyk of the Paterson Diocese as the vice postulator.

Father Tomczyk finds many reasons for considering the monk for sainthood.

“Many people identify with him,” he told the Register, adding that he could be an inspiration to seamen and mariners. “There’s a Korean component. He is celebrated in some fashion in their country as a hero.” He also said many Korean Catholics turn to him.

Father Tomczyk told the Register that Brother Marinus is inspiring to him personally.

“I find the thing most inspiring to me is the humility,” he said of Brother Marinus, explaining how, despite his leading the heroic journey and mission to rescue all those refugees, risking his life and the lives of his crew — and not losing a life but gaining five — he remained humble. “This is really inspiring.”

Such wartime action meant Capt. LaRue could have become very well known in the world, following news reports. “And yet he was invited to abandon all of that and become a simple monk. He didn’t become a priest; he became a brother. He went from a position of authority and leadership, well respected, to this simple monk who would be scrubbing the dishes and being a bell ringer and a servant at the gift shop for 47 years of his life,” Father Tomczyk explained.

Father Tomczyk reflected on the message of Brother Marinus’ life: “At the end of the day, it’s faithfulness, and holiness has always been identified with that faithfulness — being persevering to what God called you to do. When God called him to exercise courage and trust, he responded. Then the circumstances changed, and he also responded when God called him to a simple life where people would forget about him. He was not a priest. He did a lot of work behind the scenes. That is holiness. He would be a great inspiration to the faithful in general.”

“He never told anybody. When the word got out [about his war record], he didn’t want to talk about it,” Father Tomczyk said. “We have a record of him not wanting to be praised. He was not obnoxiously proud of it and telling the details in the story — [that] speaks to his humility. It’s from the Gospel: ‘I’m an unprofitable servant.’”

He noted that Brother Marinus refused to accept awards “because he never considered that to be anything heroic. He felt that’s what was needed to do; it was his responsibility.”

One time he did leave the abbey in obedience to his abbot, who instructed him to go to Washington in 1960 to accept an award.

By special act of Congress, for his bravery and leadership, he received the Merchant Marine Meritorious Service Medal, the Merchant Marine’s highest honor; his crew also was decorated, and the SS Meredith Victory was given the title of “Gallant Ship,” the only Merchant Marine ship and crew serving during the Korean War to receive such an honor.

Then, in God’s timing, there was another Korean “rescue” in 2000, but this time it was the Benedictine abbey. Vocations had dwindled, and St. Paul’s Abbey was facing closure. The archabbot turned to the abbey in South Korea and asked Father Samuel Kim, the administrator, if he would help save St. Paul’s. Father Kim accepted two days before Brother Marinus died at the abbey. Two months later, six Korean monks arrived at the New Jersey abbey, which then became a vibrant spiritual center for Korean Catholics.

Father Tomczyk pointed out that one of the Benedictine monks was Father Antonio Kang, who as a 5-year-old boy was with his parents on that rescue ship in Hungnam in 1950. “If you’re a person of faith, it cannot be accidental,” he said. “It’s God’s providence.”

Bishop Serratelli also saw it as providential. He wrote, “I do not think it is a coincidence that Capt. LaRue saved 14,000 Korean refugees and, decades later, Brother Marinus’ abbey is saved from closing by the arrival of Korean monks.”

The total scope of what saving those 14,005 lives on the “Ship of Miracles” would lead to is incalculable. In one case, saved were the parents and sister of South Korea’s current leader, President Moon Jae-in, born on Geoje Island two years later. In 2017, during a memorial ceremony at the National Museum of the U.S. Marine Corps in Virginia, he told of his parents’ rescue. “Had it not been for the valiant warriors of the Chosin Battle and the success of the Hungnam Evacuation,” he said, “I would not even exist today.”

Father Samuel, St. Paul’s prior, told the Register that while in seminary in Pittsburgh in 2000, he passed by Brother Marinus’ room, “and I saw him, but I didn’t know about his career at the time.” Although his own father, who died 35 years ago, never spoke of which ship, cargo or military carried him out of Hungnam harbor, he was one of the refugees saved during that evacuation effort.

Together, at Compline, the monks at the priory “pray the prayer for his canonization every day,” he said. Whenever Koreans visit the monastery, as many did before the pandemic, “they also visit his grave at our cemetery,” Father Samuel added. They start at the statue of Our Lady in a Mary garden and walk along the 300 apple, pear and cherry trees he began planting from the monastery to the cemetery in 2017.

Now the task before Father Tomczyk includes looking for personal devotion to Brother Marinus, interviewing witnesses and establishing his heroic virtue and holy life. A prayer for his intercession has been composed.

If all goes well, someday Philadelphia’s Sts. Katharine Ann Drexel and John Neumann will have another native Philadelphian join them at the altars — Brother Marinus LaRue.

Father Sinclair Oubre, diocesan director of Stella Maris, a Catholic apostolate for people of the sea, in the Diocese of Beaumont, Texas, has had a devotion to Brother Marinus since learning about him. Working as a merchant mariner himself during summers while he was in the seminary and then involved in maritime ministry since 1988, he knows firsthand about seafarers’ personal needs and the many prejudices they encounter.

“My devotion has grown out of these different elements,” he told the Register. Brother Marinus’ example and cause shows “the importance of elevating merchant mariners in their lives and given someone who manifested holiness and devotion, someone who was there.”

- Keywords:

- causes for canonization

- american sanctity

- sanctity in america

- sanctity in the usa

- Servant of God Marinus LaRue

- joseph pronechen