Catholicism in Nepal: A Small, Productive Church in the Himalayas

Christianity is surging in the landlocked South Asian democratic republic.

KATHMANDU, Nepal — Catholic religious orders brought Christianity to Nepal — twice.

Capuchin friars from northern Italy were assigned by the Vatican’s Propaganda Fide in 1703 to plant the faith in Tibet. Six set out; two made it. Confronted by devout Buddhist monks, the missionaries focused on merchants in Kathmandu, a nearby trading center.

The Capuchins were evicted about 66 years later, when a unified Kingdom of Nepal emerged — and the monarch suspected Catholics of potential links to the British East India Company.

Fast-forward almost 200 years: In 1951, Jesuit missionaries teaching in Patna, India, relocated to Kathmandu on the king’s invitation.

King Tribhuvan endorsed U.S. Jesuit Father Marshall Moran’s offer to establish a school for Nepali students in what was, then, the world’s only Hindu nation. Other religions were not tolerated; possessing a Bible was illegal.

The Jesuits agreed to his two rules: not to evangelize in Nepal nor to leave the Kathmandu Valley. The king’s sons, future kings themselves, Birendra and Gyanendra, had studied with the Jesuits at St. Joseph's School, in Darjeeling, India.

Christianity Surging

Today, Christianity is surging, led by evangelical Protestants.

It’s the “golden age of the Gospel,” according to the Nepali Times. One international survey ranked Nepal as having the world’s fastest-growing Christian population, with an estimated 1.3 million believers in 2020, up from 7,400 in 1970.

Bishop Anthony Sharma, the country’s first prelate, estimated eight years ago that the Christian population was more than 2 million, adding, “As far as the Catholic Church is concerned, we followed the instruction of the king. … We never went out preaching aggressively the Gospel.” (Pope Benedict XVI raised the local Church’s status to an apostolic vicariate in 2007. Bishop Sharma was the first vicar.)

Today, Catholic priests, women religious and dedicated laypeople perform great service, especially through 37 schools (including a college, 18 high schools and two technical schools), educating more than 30,000 students; Caritas Nepal; and social-welfare programs for the elderly poor and mentally ill.

But with membership stuck below 8,000 believers for more than a decade, it seems the Jesuit agreement to “teach not preach” continues to shape the Church — and pinch evangelization.

‘Stepping Into 90’

Buoyant children in crisp blue-and-white uniforms snake in neat lines through the handsome campus of St. Xavier’s School in Lalitpur, a garden of purpose in the center of the chaotic Kathmandu Valley. More than 2,500 students in grades K through 12 attend this prestigious institution, divided about 60%-40% between boys and girls, according to the principal, Jesuit Father Samuel Simick. It’s the direct descendant of the school Father Moran founded. (Nearby is St. Mary’s High School for girls, which opened in 1955, run by the Sisters of the Congregation of Jesus.)

“Namaste! Namaste!” intone little boys bowing toward the principal, who explains to me that the school is self-sufficient based on tuition of around $500 a year. About 15% of the students receive aid. Most students are non-Catholic: “Mostly Buddhist, some Hindu and some Muslims — we have prayer rooms,” explained the principal, adding “Nepal is a wonderful place where religions coexist peacefully.”

Father Simick was born in Darjeeling, India, the youngest of nine children. His older brother, Bishop Paul Simick, is Nepal’s apostolic vicar; their sister, Cecilia, belongs to the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth congregation.

On the school’s edge is the Jesuit residence where I met Father Cap Miller. He will be “stepping into 90,” in December, using a local term for having a birthday. Father Miller arrived in Nepal on Sept. 2, 1958, from his hometown in Lakewood, Ohio — mobilized by the Chicago Province of the Society of Jesus, at the behest of Father Moran, who needed more teachers.

“I did not want to come!” exclaimed the lively priest, who was not yet ordained when he landed. “But I was an obedient Jesuit,” which requires “going anywhere in the world where there’s need.” Besides teaching, Father Miller lived in remote villages, learned local languages and earned a degree in anthropology. He took Nepali citizenship, only allowed to a person who lives there at least 20 years.

“For the first few decades, we were the only Catholics,” Father Miller recalled. “I was told, ‘This is a Hindu kingdom with a lot of Buddhists. Get it straight: You will never see a baptism. We’re not even planting the seeds, but plowing the ground.’ We were especially careful with students because we honored broad recognition that we do not proselytize.”

Still, Fathers Miller and Sharma were arrested once, after offering Easter Mass. They spent the night in jail. Until 1993, Catholicism was not recognized by the state.

Nepal became a secular nation after abolishing the monarchy in 2008; religious freedom was already enshrined in a 1991 constitution, but it barred conversion. A law passed by the parliament in 2017 strengthened anti-conversion rules, which have been used against Christians.

Currently, two South Korean nuns are charged with trying to convert Hindus through “allurement” in a case that has dragged on for more than a year. A lay Catholic and Protestant pastor, both from South Korea, were arrested, too. (Sources close to the Church describe it as an attempted extortion.)

The Nepal Christian Society, a nationwide alliance, confirms that Christian persecution has intensified since 2018, when the anti-conversion code went into effect. U.S.-based Open Doors ranks Nepal as No. 48 out of the top 50 countries where Christians suffer for belief.

Cathedral Bomb Attack

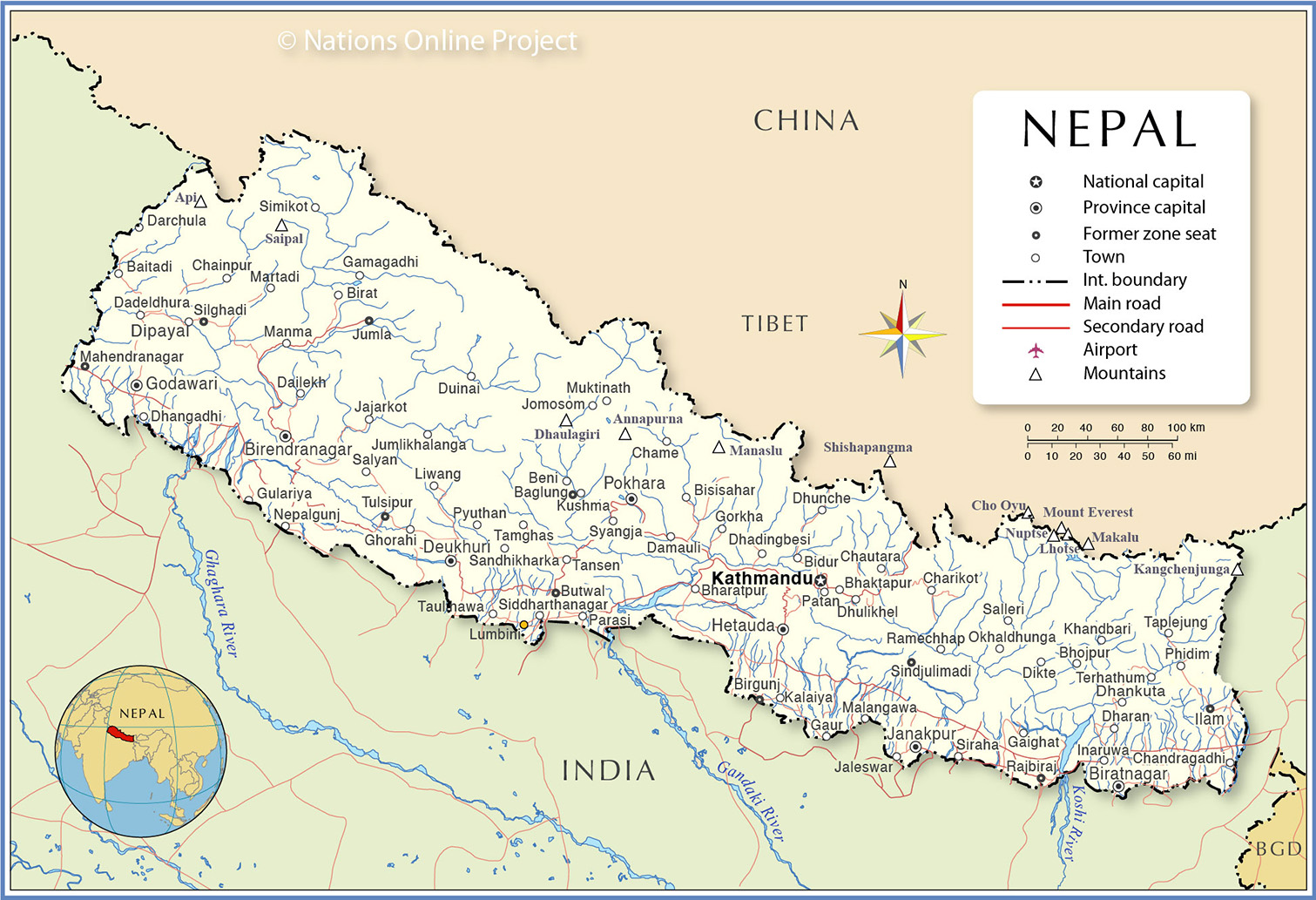

Father Silas Bogati, vicar general, cut short an international trip to attend court with the sisters. He said the social work they did in the city of Pokhara in central Nepal — helping more than 120 slum children and offering food to poor residents during the COVID-19 pandemic — exemplified Christian faith.

Father Bogati has a fascinating conversion story. At age 18, he met a Protestant missionary distributing Christian literature on Kathmandu streets. He was particularly attracted to the message of love and began using his bicycle to distribute the tracts.

At St. Xavier’s, he met Catholic priests, including Father Miller, who “was so compassionate and welcoming” and became his spiritual director. Considering the priesthood, he approached Bishop Sharma, who arranged for seminary studies in India. Eventually, Bogati was ordained in 2000, the first native Nepali priest.

On May 23, 2009, Father Bogati witnessed extreme hate. The congregation in Assumption Cathedral had just sung the Gloria when a bomb went off, “creating chaos among the faithful,” killing three people and injuring many. “People I knew before I started celebrating Mass were dead in seconds. This has haunted me and traumatized the rest of my life,” the priest noted somberly.

(The middle-aged woman who set off the bomb belonged to a radical Hindu organization; she recently was released from jail.)

Yet parishioners and peers report Father Bogati has been a great leader. As director of Caritas Nepal for 11 years, he managed a massive earthquake response in 2015, which brought international aid and innovative programs. He led resettlement of more than 100,000 Bhutanese refugees, many of whom moved to the United States.

“If we had not helped those refugees, they’d probably still be in those camps,” Father Bogati said.

First Church; Only Cathedral

At Assumption Cathedral in mid-October, Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus Octavio Cisneros of Brooklyn, New York, concelebrated Mass. He was visiting Caritas Nepal programs that partner with Catholic Relief Service (CRS), on whose board he sits.

The New Yorker said he was “very pleased” with what he observed: a three-year Caritas-CRS project that is building more than 4,000 homes for families in the country’s most remote areas. Beneficiaries are mainly Hindu and Buddhist families. Strong relationships with local governments dating back to earthquake relief benefit the work, according to the CRS team.

A group of parishioners walked with me around the beautiful grounds of the cathedral, which incorporates local motifs and Asian design elements. Built in 1995, it is the country’s only cathedral and first formal church structure.

“I grew up here,” said Charles Mendies, a Nepali executive who literally grew up on the property, which his mother donated to the Church. “Mummy,” as she was known to all, is buried on church grounds, where she once ran a home for abandoned children.

Mendies explained that he inherited a great devotion to Jesus Christ from his mother. As a young woman, she moved from Canada to work for the Salvation Army in Kolkata, India. There, she met her husband, an Anglo-Indian Catholic; Together, they moved in 1947 to Kathmandu. Their family grew to include two sons and 10 adopted children.

Although baptized Catholic and educated by the Jesuits, Mendies became “frustrated” with the order: “There weren’t even crucifixes in the classroom, and we didn’t have Christmas off!”

He met American missionaries who were intensely devout: “The ABCs of Protestant denominations were here, extreme right to left, from Assembly of God to Methodists, and they supported local Nepalis. Everywhere there was a mission, they planted an indigenous church.”

Mendies went to the United States to study theology and was ordained a priest in the Anglican Church. Back in Nepal in 1972, he traveled to remote villages, distributing Bibles and educating regular people about the word of God. Persecution was real: He was imprisoned for eight months in 1989, inspiring a United Nations protest.

“Today, the Protestant Church is self-sufficient, with four or five Bible schools. They have a lot of professionals — teachers and doctors — but plenty of conversions are from lower classes and tribal people, because when they become Christian, they are really accepted. We are all equal,” explained Mendies.

Since the Holy See and Nepal established diplomatic relations in 1983, a non-resident nuncio covers Nepal from New Delhi. It is a particularly demanding post. Mendies thinks the Church in Nepal will be stronger if the nuncio represents Sri Lanka and Nepal instead of India and Nepal. He also thinks there should be more investment in local priests and the Holy See should appoint a Nepali bishop.

Influence of a Saint

A lifelong family friend compelled Mendies to return to the Catholic fold: Mother Teresa.

While working in Calcutta, Mummy Mendies became close to Mother Teresa as the future saint began her new ministry, the Missionaries of Charity. Mummy’s family, then Charles’ family (his wife and three boys), remained close to the saint.

“Mother Teresa said, ‘You have to come back,’” Mendies recalled. “So I did.” He traveled with Mother Teresa extensively, especially to the U.S. When Mother died, her successor, Nepali Sister Nirmala, persuaded Charles to help coordinate her funeral.

Asked to share a favorite story of the saint’s heavenly qualities, Mendies recounted: “A very wealthy American brought a $1-million check to Calcutta to give to Mother. While they were meeting, Mother told the man, ‘If you really want to do something for me, go home and love your wife.’ What none of us knew, except the man and Mother’s intuition, was that the couple was close to divorce. So she didn’t take the check, and the divorce never happened!”

Charles Mendies told me this story while driving through the wild streets of Kathmandu. At the other end of the city is a program run by the Missionaries of Charity since 1978. At a very holy Hindu temple, where many poor come to die, the sisters provide food, bathing and hospice care.

As one account explains, the sisters “shy away from publicity, preferring to let their actions speak instead.”

- Keywords:

- nepal

- sri lanka

- india

- society of jesus

- evangelization