St. Joseph’s Lesson: You Can’t Love Like Christ, Unless You Are Chaste Like Christ

COMMENTARY: We’re living at a time in which probably no part of Catholic faith and life is as caricatured, contradicted, criticized, condemned, calumniated and contravened as Catholic teaching about chastity.

There are many virtues that Christian piety has predicated of St. Joseph that Catholics are called to ponder more deeply and imitate more closely. Joseph is just, faithful, obedient, humble, prayerful, silent, charitable, hardworking, provident, protective, courageous, zealous, prudent, patient, loyal and simple.

One of the most important of his virtues for our time in history, however — the one that the Church features during the litany of “Divine Praises” we proclaim during Adoration of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament — is that Joseph is “most chaste,” a title given only to him and to our Lady. It’s a translation of the Latin castissimus, a superlative that can be rendered “most,” “very” or “supremely” chaste. Against any temptation to minimize the virtue, St. Joseph inspires us to become maximally chaste.

We’re living at a time in which probably no part of Catholic faith and life is as caricatured, contradicted, criticized, condemned, calumniated and contravened as Catholic teaching about chastity. Many outside the Church, and even some inside, look at the Church’s teaching as something as outdated as Victorian clothing, as the path to repression rather than love, as training ground for prudes not saints.

The sexual revolutionaries who trumpet the right to sex with whomever we want, whenever we want, wherever we want and however we want, the culture that has contributed to the epidemic of broken hearts, marriages and families, sexually transmitted diseases, sex crimes and abuse, human trafficking, prostitution and pornography, sexual addictions, teenage pregnancies and abortions, claims that chastity is against our biology, by shackling a natural urge; it’s against our rational nature, by restraining our freedom; it’s part of the “Bad News” instead of Good.

Contrary to what many mistakenly believe, the Church’s teaching on chastity is not a type of asbestos with which to suffocate the most passionate of human experiences. It’s a wisdom that seeks to help those flames not destroy what God wants the sexual urge to lead to: real love, so that we might genuinely love others as Christ has loved us. Rather than negative and prudish, the Church couldn’t have a more exalted appreciation for human love and the chastity that makes it possible.

In the midst of this widespread misunderstanding and mockery of the Church’s teachings on human sexuality, not to mention the mounting misery that has come from its rejection, there is added urgency for the Church to help Catholics and non-Catholics alike to recapture, treasure and protect the truth and beauty of chaste human love.

The stakes are enormous. St. Paul, immediately after giving the ancient Christians in Thessalonica the summary of our Christian vocation — “This is the will of God, your sanctification” — tells them immediately, as an elucidation of that summons, to “abstain from porneia” a Greek term that refers to all sexual sin and is generally translated as unchastity.

Since holiness is the full flourishing of love in a human person, one cannot truly love unless one is chaste. Chastity is indispensable for us to become fully human, holy and eternally happy. The gospel of chastity, therefore, is an essential part of the Church’s mission for the salvation and sanctification of the human race.

To act on this summons, it’s essential to know what chastity is. Even among clergy, religious, consecrated and catechists, chastity is regularly confused with continence (abstinence from sexual activity) or celibacy (the state of being unmarried). When the Catechism emphasizes that “all Christ’s faithful are called to lead a chaste life in keeping with their particular states of life,” and that “married people are called to live conjugal chastity,” many married couples are left scratching their heads, wondering how they can be both “chaste” and start a family. The reason for the confusion likely stems from the fact that when term “chastity” is often used, it’s employed in the context of the sexual education of teenagers (who are called to continence in chastity) or in the description of the promises or vows professed by priests and religious (who are called to celibate continence in chastity).

The confusion points to the urgency and importance for all in the Church to understand what chastity is and how all the baptized — married couples, singles, priests, consecrated, those with same-sex attractions and opposite-sex attractions — are called to it.

The first step in the Church’s teaching on chastity is found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The Catechism describes chastity as a vocation, a gift from God and a grace, but at the same time it talks about it as the “fruit of spiritual effort” that includes the “apprenticeship in self-mastery” so that the person “governs his passions and finds peace” rather than letting himself be “dominated by them.” It’s linked fundamentally to the virtue of temperance or self-control. This self-mastery is a “long and exacting work,” it goes on to say: “One can never consider it acquired once and for all. It presupposes renewed effort at all stages of life.” But the end is a “successful integration of sexuality within the person and thus the inner unity of man in his bodily and spiritual being.”

Chastity, therefore, is a “school of the gift of the person that leads to a spiritual communion,” based on Christ’s chastity, which is at the basis of all friendship, not to mention other relationships.

But that look at chastity as the temperate integration of the sexual urge never struck Pope St. John Paul II as adequate. The sexual urge is meant, he wrote in various pre-papal essays, to lead us ecstatically out of ourselves to communion with others and God, to recognize that we are not self-sufficient.

Moderating the sexual urge is not the main point; we need to orient it appropriately so that it actually brings about communion rather than destroys it. Chastity is not linked fundamentally to temperance, he wrote in his 1960 work, Love and Responsibility, but rather to love. In contrast to lust, which “reduces” another person to the values of the body or erogenous zones and which “uses” others for their own emotional or physical gratification, chastity is the moral habit that raises one’s attractions to and interactions with another to that person’s whole dignity, body and soul.

In his papal catecheses on “Human Love in the Divine Plan,” popularly called the “theology of the body,” St. John Paul II taught that the virtue of chastity is likewise bound to the virtues of purity and piety. Purity impacts our vision: “Blessed are the pure of heart,” Jesus taught, “for they shall see God.”

Purity allows us to see God in others, to recognize a reflection of the image of God. Piety is the habit that helps us, once we’ve remembered or recognized that no other person is a “mere mortal,” to treat that person according to the image of the Divine Giver in them. Linked to piety, chastity helps us to see and treat the other as sacred subject instead of a sexual object.

Chastity, therefore, is connected to all four virtues — self-control, love, purity and piety. It’s what helps us keep our romantic love (eros) capable of the love of friendship (philia) and true Christian self-sacrificial love (agape). Living chastely does not relegate people to a “loveless life” but makes true love possible, through the integration of eros consistent with philia and agape.

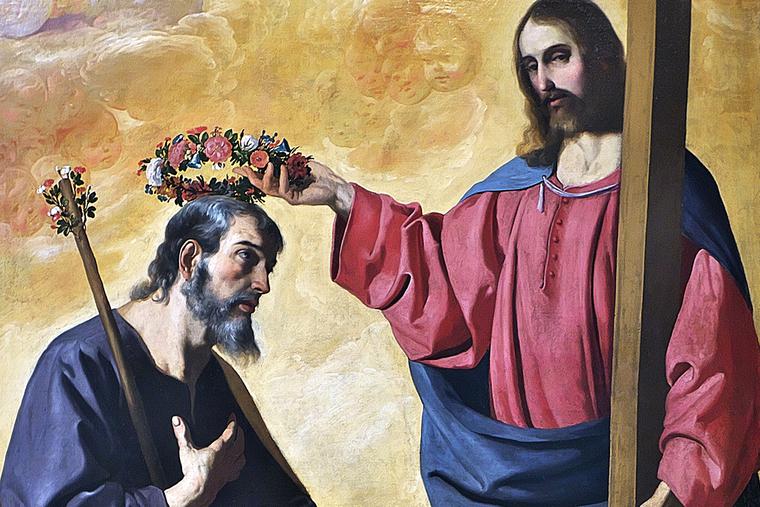

St. Joseph shows us this type of chaste love to a maximal degree. Contrary to some Christian art that depicts him looking the age of Mary’s great grandfather, Joseph was certainly young enough to journey through the desert twice and to be a tekton (“construction worker,” far more than carpenter), one of the most physically demanding of ancient professions. Yet even though he was young and manly and lived with the most attractively virtuous woman of all time, he kept his love for her “most chaste,” seeing God within her during her pregnancy and beyond and reverencing her with pure love.

St. Joseph is the model of a Christian gentleman who regulates and channels his love for his wife according to that woman’s vocation and overall good, rather than his own desires and needs.

That is why Christians in every age bless him before the Eucharistic Son of God he raised, recognizing that the most fitting form of praise is imitation.

- Keywords:

- chastity

- st. joseph