The Fire of Heraclitus and the Flame of Christ’s Love

‘Christ’s Resurrection is … a transcendent intervention of God himself in creation and history.’ (CCC 648)

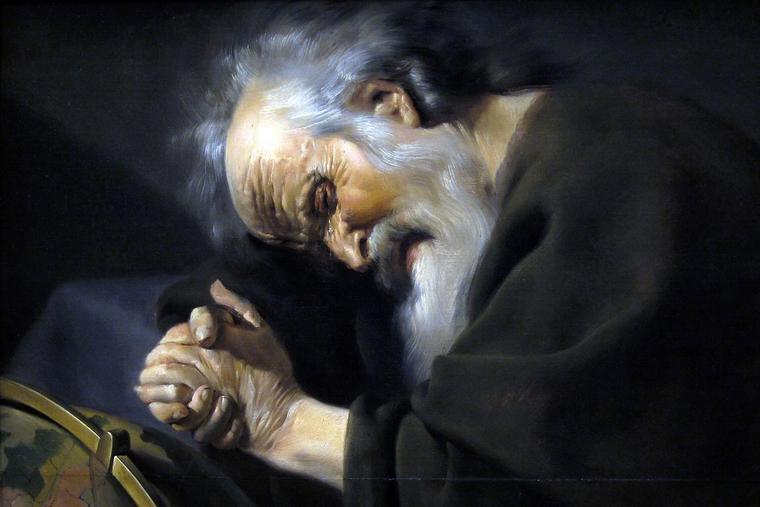

Five centuries before the longed-for Eucatastrophe that would change everything, there lived a Greek philosopher by the name of Heraclitus. Who was so fixated on the idea of change that for him the only constant in life was that there weren’t any constants. One could never step into the same river twice, he declared, because the movement of the water at any given moment would never be the same.

To make his case, Heraclitus pointed to the power of fire, seeing in its destructive force the defining emblem for a world forever in flux. Of which, for him, the most painfully obvious example was death. What could be more chillingly commonplace than the sheer blinding finality of death? That none of us gets out alive is surely the one change we will all be forced to face. None of us, therefore, is immune from the basic impediment to being born, which is that it comes with an expiration date telling us we must also die. It is the undeniably conclusive cancellation of all that we hope to acquire, which is to say, the illusion of immortality.

It is not within the reach of mere mortals, of finite beings rooted in bios alone, to launch that rocket ship. If you wish for more, then you’ll need Zoe, which nature does not provide. Or, put it this way. Life is a game of chess and the first lesson to be learned is that you cannot win. That is because your opponent — Death — never loses. He will checkmate you every time.

We are all bound for the dark, in other words, our brief candles snuffed out in the great sea of death. “Golden lads and girls all must,” says Shakespeare, “As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.” The bright day will soon be done, leaving us all to go down with the sun. Bound for that “undiscovered country,” he calls it, “from whose bourne no traveler returns.”

Not even Lazarus, who, for all that he came back from that place, had anything really to say about his journey into the nether world. One imagines him sitting mutely at meals with his sisters, each gently urging him to get on with his food. The poor man might as well have stayed dead. It is, writes the poet Philip Larkin, “The sure extinction we travel to, / Nothing more terrible, nothing more true.”

“So, Mr. Henry James,” asked one of his admiring readers, “tell me what you think of life?” To which the master storyteller replied, “I think it is a predicament which precedes death.” And when, not long after, he found himself about to die, he greeted it with his customary courtesy: “So, here it is at last, the distinguished thing!”

But it isn’t at all distinguished, is it? In fact, it is the most egalitarian experience of all. I mean, it gets to happen to everyone. Nor is it any sort of achievement, either; like climbing the Matterhorn, or mounting another stair on the corporate ladder of success. It is instead a disintegration, a final, disastrous fall into the same abyss that will claim us all. Dying is really no big deal, as someone once said. “Living’s the trick.” And most of us don’t seem to manage that very well, do we?

Anyway, Heraclitus appears to have been onto something here. That in the midst of life, to recall a line from the Book of Common Prayer, there is always death. “Flesh fade, and mortal trash / Fall to the residuary worm,” reports Gerard Hopkins in a poem which, in giving Death his due, concedes a fair amount of the high ground to Heraclitus, too. And if our acknowledgment of that fact is to be an honest and undistracted attention paid to our own impending deaths, we will need no little courage to do so. Screwing one’s courage to the sticking place, is never an easy thing. Not when having to face, undismayed, the awful truth, which is, as Hopkins sets it all down in words Heraclitus would approve: “world’s wildfire, leave but ash …”

Nature’s end is not pretty; a state of entropy never is. And to the extent we are part of nature, it is ours as well. But there is more. A lot more, and it is at the heart of the Good News Christ came to tell us; indeed, to show us in the last reaches of a death he freely endured. Hopkins enshrines it beautifully in the last, decisive phase of the poem, which is utterly triumphant. In the title itself, in fact, we glimpse the tipping point, i.e., “That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and on the Comfort of the Resurrection.”

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, / Since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, / patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

Here, then, is the long awaited Eucatastrophe, to use the word coined by J.R.R. Tolkien, which means a sudden and altogether unexpected turn in the relentless and unending tale of death and disaster; when, seemingly victorious, they are at once thoroughly vanquished by a love far greater than death. “The good catastrophe,” he calls it, “the sudden joyous ‘turn’ … It denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat. … Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.”

And why does it pierce the soul with a joy that makes one weep? Because, says Tolkien, “it is a sudden glimpse of Truth, so that your whole nature chained in material cause and effect, the chain of death, feels a sudden relief as if a major limb out of joint had suddenly snapped back … that this is indeed how things really do work in the Great World for which our nature is made.”

Poor old Heraclitus. He could not have known this living five centuries before the coming of Christ, who would gladly have told him. Let us hope he knows now.

- Keywords:

- Jesus christ

- resurrection

- heraclitus