Following Jesus Christ — This Is What It Means to Be a Christian

Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!

Unlike Elvis, about whom there have been no end of alleged sightings — from Memphis to the moon — nearly all the Jesus sightings we have on record are confined to the New Testament. Of course, these carry the distinct and undeniable advantage of having actually happened. They are not mythological accounts, in other words, but real historical events retrieved from the great sea of the past.

For instance, there is the sighting which takes place in Bethany, where Jesus is first seen by his cousin John, who’s kept himself busy baptizing Jews in the nearby Jordan River. The scene is described by the author of the Fourth Gospel, St. John the Divine, who also happens to be part of the story he’s telling. It seems that an official delegation from Jerusalem has been sent to sort things out concerning this strange sun-baked fanatic from the desert. “Who are you?” they demand to know. His answer is wonderfully simple and direct: “I am not the Christ. … I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord,’ as the prophet Isaiah said.”

So, if he’s not the promised Messiah, why is he baptizing all these people? “I baptize with water,” he explains, “but among you stands one whom you do not know … the thong of whose sandal I am not worthy to untie.” And with what, pray, will he be baptizing? The Holy Spirit. Thus, when John sees him coming toward him, he will exclaim: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!”

It is what follows upon this announcement, however, that is the real flash point of the story. Because, no sooner has he identified Christ, telling everyone who will listen that it is no less than the Lamb of God himself passing by, that two of his own disciples, Andrew and John, suddenly peel away and begin to follow Jesus, embarked upon a journey that will never end. In four perfectly simple, hardworking words everything changes: “and they followed Jesus.”

Those four words, I put it to you, are emblematic of everything we need to know in the Christian life. If you want to know what discipleship means, there is the formula for you: following Jesus. Yes, even if it leads all the way to the Cross. For there is no other way to the Father, to the source of all that will save us and make men glad.

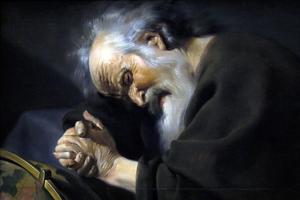

Everything crystallizes, by the way, in the brief exchange that takes place among them soon after they’ve left the John who only baptizes with water. Riveted by the sight of Jesus, of the one who will baptize with more than water, the two set out at once, but keeping a discreet distance from him, hesitant even as they draw nearer to him, closing in on what will be their destiny. Here is the fateful contest, the tension of the struggle between fear and hope, whose final outcome only God knows.

And Jesus, knowing what is on their minds and in their hearts, suddenly turns round to ask: “What are you seeking?” It is the perennial question, the one which most deeply reveals who we all are, the thing that will shape the lives we live in a Christ-like way. We are all seekers, in other words, our lives set upon a quest, looking for what we do not yet have. But hoping, always hoping in however dim and inchoate a way, to find out what it is. And in the answer that they will be given, we may all learn what it is we are really looking for, the mysterious Other for whom we have all been searching.

Which is why they must first ask, indeed, why they are moved to do so. “Where do you live?” They need to know this. Because whatever it is they are looking for, what we are all looking for, must have a place, must be somewhere in time and space; it cannot be left to abstraction and surmise. “I am only a man,” says Czeslaw Milosz: “I need visible signs. / I tire easily, building the stairway of / abstraction.”

When a man sets out looking for God, if he is to see him, breathe in his being amid the things he knows, God must become one of those things, becoming himself a man. Otherwise he remains utterly unrecognizable. Milosz knew this, of course, and so in his poem “Veni Creator,” he reminds us “that signs must be human,

therefore call one man, anywhere on earth,

not me — after all I have some decency —

and allow me, when I look at him, to marvel at you.

And in the answer that Jesus gives them, we see how things will turn out, that they will have at last found what it is they have been looking for all their lives. “Come and see,” he tells them, thus inviting them to the promised consummation to come.

This is what it means to be a Christian. It is not an idea or a concept around which one then organizes one’s life. It is not a set of principles to which one is expected to adhere. Rather it is an encounter with Someone who speaks and acts like no other person one has ever met. Someone who speaks with commanding, compelling authority, whose very singularity marks him off as absolutely unique, unprecedented in all of time or space.

“If I don’t believe this man,” you say to yourself, “I’ll not believe anyone.” Here an eternal meaning has been found, laid hold of in the shape of one man, who happens to be the very Logos of God himself, all at once concretely incarnate in the human being Jesus. Here heaven and earth are joined, wedded together within each moment of time, within every space.

“May it become,” says Luigi Giussani, Servant of God, “habitual to perceive in all things — in everything, from the boughs of the tree to the hairs of the person you love — the presence of the Mystery that became a man in flesh and blood. … Getting used to seeing this in everything is a history that God allowed you to begin.”

- Keywords:

- disciipleship

- Jesus christ