The Blaine Amendment Ruling: A Glass Half Full?

Blaine Amendments are nothing less than open declarations of religious hostility.

Lots of Catholics were happy at the June 30 Supreme Court decision in Espinosa et al. v. Montana Department of Revenue, striking down the Blaine Amendment to the Montana State Constitution. It is cause for happiness, but perhaps a happiness that is tempered: The ruling was rightly decided, but does it go far enough?

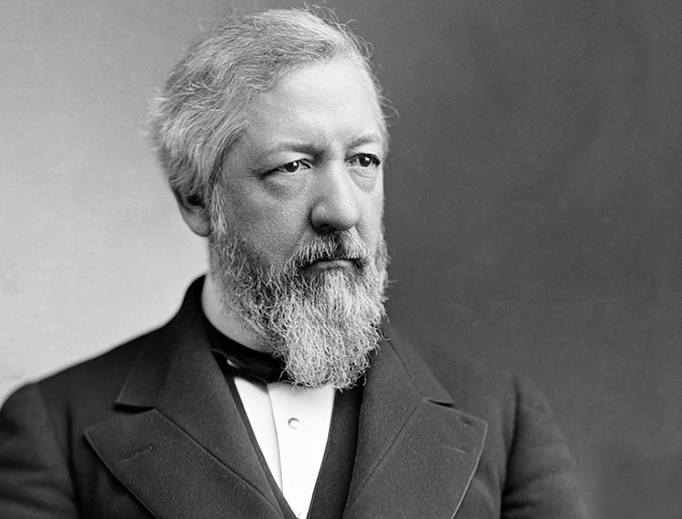

Short history lesson on Blaine Amendments. James G. Blaine was a leading Republican politician of the second half of the 19th century. His achievements included being Speaker of the House, Secretary of State, and Senator from Maine. The apex of his political career was losing to Grover Cleveland for President in 1884, a particularly ugly campaign where Blaine highlighted Cleveland’s fathering an illegitimate child (“Ma, ma, where’s my pa? Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha”) and Cleveland exposed Blaine’s correspondence in which he pushed railroad legislation that later proved personally profitable (“Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine! Burn this letter!”).

Of course, we could mention the ugliness of Blaine’s anti-Catholicism. In 1875, scandal-ridden President Grant pushed for states to fund public schools while making a rigid separation between church and state. House Speaker Blaine saw an opportunity to divert attention from administration scandals while ingratiating Republicans with the Protestant establishment. He offered a Constitutional amendment to prohibit any aid to religiously-affiliated schools. The amendment never made it through Congress, but like-minded bigots took up its cause in individual states, 37 of which incorporated Blaine-like provisions in state constitutions. Subsequent jurisprudence has interpreted those amendments in some states (including Montana) very strictly, in others more liberally. (A map of state Blaine amendments is here.)

Blaine Amendments were in part responsible for the secularization of broad swaths of Catholic higher education. In the 1960s, parochial grade or high schools (dioceses still had not largely scooped up control of secondary education) would have had a hard time not looking Catholic, but colleges and universities could mask their religious identity more easily. My alma mater, Fordham University, divested itself of crosses in classrooms to assume a “Catholic tradition” rather than a “Catholic identity.” (I remember a Hungarian Jesuit friend invited me to lunch at Loyola-Faber Hall around 1983, He marveled at how, under martial law, Polish school children had risen up to defend a crucifix in their schoolroom. I noted that “in Poland, we only had Communists to deal with. If we’d had some Jesuits, you would have seen those crosses go!”)

So, in invalidating the Montana Blaine Amendment, the Supreme Court rectified an injustice about 145 years overdue: disqualifications based on religion, motivated at worst by anti-Catholic animus and, at best, by momentary cynical political calculation. That’s good.

But is it good enough?

Espinosa was a 5-4 decision: the four “liberal” justices dissented, seeing no problem with religiously-based discrimination ensconced in positive law. So Catholics won this one by the skin of their teeth.

I am not a full-throated cheerleader for Espinosa because of another Supreme Court decision, Masterpiece Cake Shop v. Colorado.

In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled in Masterpiece that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission violated Jack Phillips’ rights in compelling the baker to make a wedding cake to celebrate a homosexual wedding. While Catholics also feted Masterpiece, Jack Phillips is back in the maws of the Colorado bureaucracy, having to re-litigate the rights he supposedly won in the Supreme Court two years ago. Masterpiece was hardly a full-throated endorsement of religious conscience and freedom. The Court smacked down Colorado in 2018 in large part because the proceedings of its Civil Rights Commission against Phillips were egregiously and openly biased against the owner’s Christian convictions. The lesson of Masterpiece seems not so much that “free exercise” guarantees freedom of conscience but if you’re going to be anti-religious, at least be more discreet about it. It strikes me much like Alasdair McIntyre’s observation about Kant’s Categorical Imperative (moral rules must be always universalizable): The only people it stops are dullards not creative enough to add enough conditions to circumvent it.

Blaine Amendments are like Masterpiece: open declarations of religious hostility. For a Court (or at least some members) that doesn’t like such overt prejudice, the Blaine Amendment could not pass muster.

I am encouraged by the pro-free exercise of religion jurisprudence struggling to be born in the Supreme Court. The 7-2 split of the Court was encouraging and Justice Thomas went out of his way to say he would give good faith deference to religious institutions to classify positions under the “ministerial exception” waiver. Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor were the holdouts.

Both cases involve application of federal anti-discrimination employment laws. The question was whether teachers in a Catholic grade or high school fall under the “ministerial exception” shielding religious institutions from government scrutiny in their employment practices. Opponents argue that they do not, because a teacher only offers religious instruction for part of the day, while the balance of the teacher’s schedule includes subjects no different from a public school counterpart who would be under those laws.

The opponents’ argument, however, fails to understand what a religious school is. The argument instead tries to force a religious school into a “one-size-fits-all” educational model (the norm for the model being the public school).

But a Catholic school is not just “basically a public school” that becomes Catholic during sixth period when Ms. X is teaching religion. A Catholic school is always a Catholic school. It is (or at least should be) permeated by a religious ethos in which all instruction is influenced by a Catholic worldview. That means that health and sex education in a Catholic school is not going to look like its public school counterpart. It means that talking about history is not going share secular conceits commonplace elsewhere. It means that choices in reading and ways of studying literature are (or at least should not) be driven by postmodern, relativistic biases. A Catholic school teacher is not Catholic for one school period, any more than a Catholic politician (certain “personally opposed” types notwithstanding) is a Catholic on Sunday and just like everybody else on Monday.

THAT perspective is controversial.

It’s tied up with all sorts of other issues, like whether institutions can have ethical identities or consciences. It’s the same reason the Little Sisters still had to re-litigate their right not to pay for abortifacients. (They also won July 8.) Certain people will simply not surrender the notion that an institution cannot have a moral conscience.

(Of course, they don’t really believe that. They only claim it when they disagree with the conclusions of an institution’s moral conscience, e.g., when it is pro-life. If you think they consistently believe that, just ask about “corporate responsibility” and “social justice concerns,” public confession of which is so in vogue these days among the Fortune 500).

Espinosa represents progress against overt legal barriers than discriminate against religion, which demand the religious citizen strip off that identity as the price of participation on what Richard John Neuhaus once called “the naked public square.” The Guadalupe decision encourages us to hope for more fuller protection of conscience rights. Whether religious citizens can cloth that public square, or whether they just get to wear a fig leaf, requires further insight. Remember that the Little Sisters won today thanks to a Presidential regulation that protected their claim to religious liberty, a rule this administration promulgated. It’s not a federal law. What one President giveth, another “with a pen and a phone” can taketh away.

For today, let’s take the win. But this issue is far from over.

- Keywords:

- blaine amendments

- religious freedom