The First Thing You Should Know About the Four Last Things

We should make no mistake: Heaven is real. Hell is real. Purgatory is real.

When we read the epistles of Saint Paul, there’s a tremendous sense of urgency. Just look at Saint Paul’s first epistle to the Thessalonians. The Apostle writes (1 Thessalonians 5:1-5):

Concerning times and seasons, brothers, you have no need for anything to be written to you. For you yourselves know very well that the day of the Lord will come like a thief at night. When people are saying, ‘Peace and security,’ then sudden disaster comes upon them, like labor pains upon a pregnant woman, and they will not escape. But you, brothers, are not in darkness, for that day to overtake you like a thief. For all of you are children of the light and children of the day. We are not of the night or of darkness. Therefore, let us not sleep as the rest do, but let us stay alert and sober.

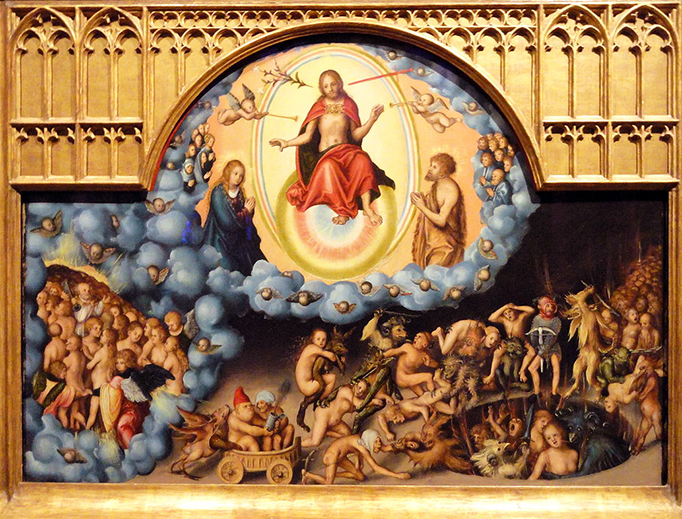

As we well know, the sense of the eschaton was greater in the early Church. What is the eschaton? It is the end time. Eschatology is the study of the reality of the four last things: death, judgment, Heaven, and hell. Sadly, the four last things are not preached about very often today. and, when they are, there seems to be some confusion concerning them. But the early followers of the Way, who daily were risking their lives because they believed in Christ, who were considered enemies of the state due to their faith, truly believed that, at any moment, Jesus, King of Glory and Lord of the World could descend, just as he had ascended, to judge each man according to his deeds.

When Jesus didn’t come back after a year, after ten years, or even after fifty years, perhaps the early Christians, facing death for their Faith, began to lose heart. Perhaps some even fell away. Evidently, Saint Paul felt that the best way to bolster the young Church was to exhort it to hold tight to hope in Christ’s coming. Hence 1 Thessalonians. Christians, over time, began to forget that, at any moment, the Bridegroom could come again, like a thief in the night, and they could be caught wallowing in the mire of their own fear. Saint Paul wanted to remind them what a great reward lay in store for their perseverance amidst persecution.

As history progresses, when the danger of being Christian seemingly fades, when Christianity becomes, in a sense, mainstream, as it did after the edicts of the Emperor Constantine throughout most of western civilization, men and women can lose sight of the last things.We can put our focus on things of less importance. We might settle into daily routines, the concerns of daily life becoming more and more important. We may begin to focus on the little things of life, naturally enough, and begin to miss the big picture. We might miss the forest for the trees. Made for immortality, we may become stuck in immorality.

The same is true today. In the United States, Australia, and parts of Europe, we have largely lost the eschatological edge that Saint Paul wanted to instill in the Thessalonians. We are complacent instead of living in our awareness of Christ’s return. I think that we need to reclaim the eschatological edge as soon as possible, if we are to regain the proper focus in the Christian life. In reality, where the cult of political correctness reigns, we may not be physically killed for our faith, but we are considered completely irrelevant and an enemy by a not insignificant portion of society. This type of persecution oppresses Christians and threatens our hope even today. Today, in parts of the Middle East, in parts of Africa, and in other places, being Christian can and still might get you killed, as in the early Church.

We were blessed as a universal Church by the publication of the Catechism of the Catholic Church under Pope Saint John Paul II. We need to look no further than to the Catechism to learn exactly what we as the People of God, the Church, need to know and believe concerning the four last things. It can be found in the Catechism, nos. 1020-1065. We should make no mistake: Heaven is real; hell is real; and Purgatory is real. And, in our lives on this earth, we should aim for Heaven by living lives of virtue. If we only try for Purgatory, and we miss, we end up in a place no one wants to be!

The systematic theologian, Paul Tillich, asked what our area of ultimate concern is. What did he mean? It’s a theological term for something actually pretty simple. In our lives, we have plenty of real concerns: health, career, and so many other aspects of the daily grind. But, if we were asked, what is really our ultimate concern, on what really do we base our lives, what would we say? Tillich stated that our religion has to be our ultimate concern. It will be the only thing that will survive when this material world passes away. According to this Protestant theologian, offering us Catholics some good advice, our faith, the daily living out of our religion, has to truly be the area of our ultimate concern. It has to be that which animates us, that which we think about when we consider our life’s decisions. Do we really believe that our actions and attitudes lead us towards the Lord or away from the Lord? Are we aiming for Heaven or heading directly away? Do we know that the Lord, who is Savior and Redeemer, who is the Lord of Mercy, but also the Lord of Righteousness and the Just Judge, is coming at a time when we do not know? This should not frighten us but should make us realize that all this stuff—death, judgment, Heaven, purgatory, and hell—is very, very real. What is our ultimate concern? If it’s not the salvation of our immortal soul, then we need to reevaluate our lives.