Wives of Priests Reveal Their Unique Vocation as Spiritual Mothers

Eastern-Catholic spirituality sheds light on the vocation of the wife of a married priest in both the Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches.

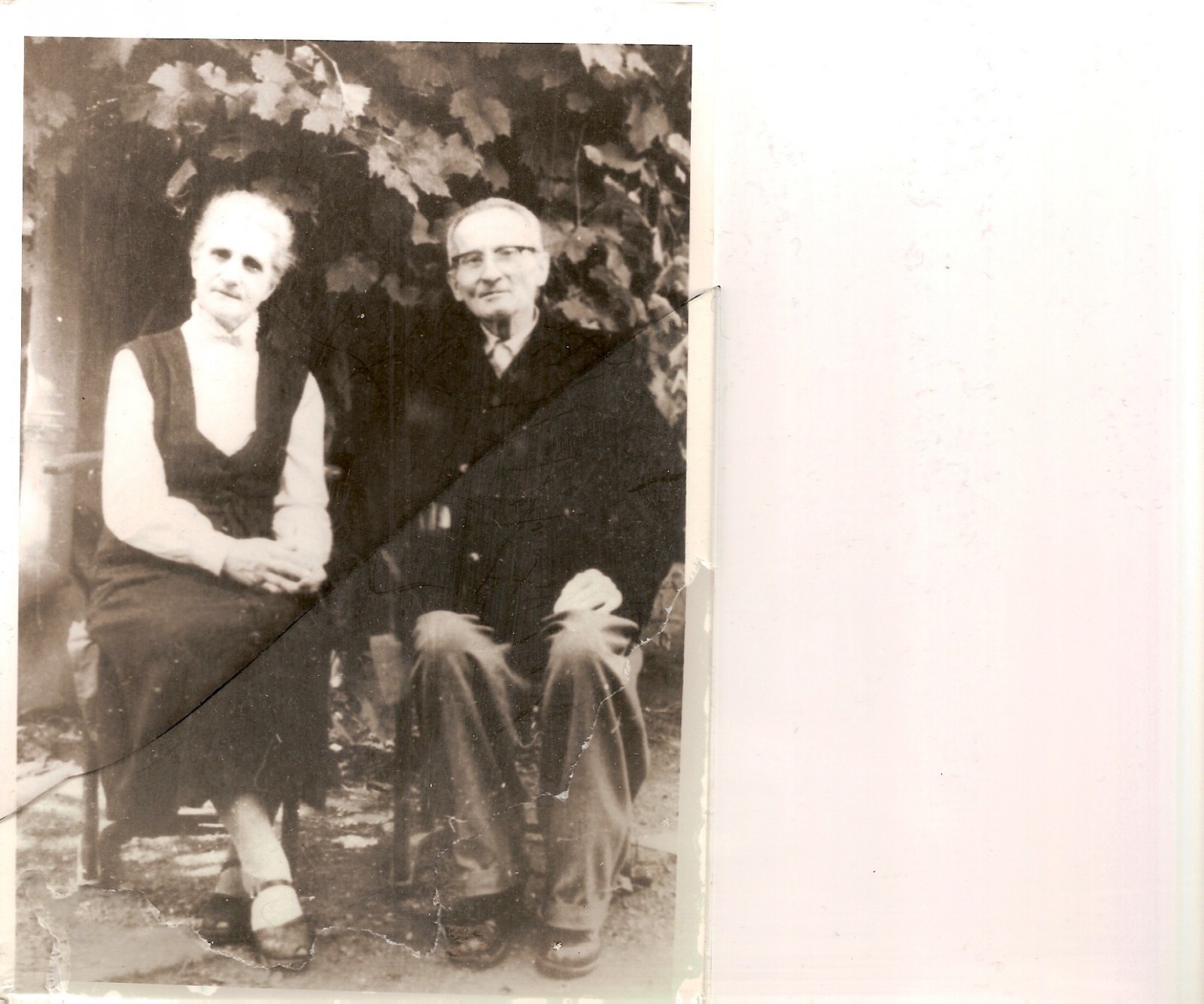

![Above, Father Doug Grandon and his wife, Lynn, both serve the Archdiocese of Denver. Below in descending order: [first photo] Father Hezekias Carnazzo, his wife Linda, and their children with Bishop Nicholas Samra on ordination day; [second photo] Father Mykhailo and his wife Orysia Hanushevsky in 1956 after returning from 10 years of Siberian exile they endured with the two youngest of their nine children; and [third photo] Father Roman Galadza, and his wife, Irene, with grandchildren Nos. nine and 10. Above, Father Doug Grandon and his wife, Lynn, both serve the Archdiocese of Denver. Below in descending order: [first photo] Father Hezekias Carnazzo, his wife Linda, and their children with Bishop Nicholas Samra on ordination day; [second photo] Father Mykhailo and his wife Orysia Hanushevsky in 1956 after returning from 10 years of Siberian exile they endured with the two youngest of their nine children; and [third photo] Father Roman Galadza, and his wife, Irene, with grandchildren Nos. nine and 10.](https://publisher-ncreg.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/pb-ncregister/swp/hv9hms/media/20200827010856_5f46f6c1c2bf74d8ccd9b86djpeg.jpeg)

FRONT ROYAL, Va. — Linda Carnazzo knew that when she was dating her future husband that he might have another vocation as well: to serve as a priest in the Melkite Greek Catholic Church.

Which meant she had to discern seriously another vocation: whether she could take up the maternal vocation of the priest’s wife.

“He brought up the idea and asked me to take it into account,” Carnazzo said of her husband, Sabatino, who was a member of one of the Eastern Churches in communion with the Bishop of Rome.

She told the Register that they met at Christendom College, a Catholic liberal arts school based in Front Royal, where they currently reside, and were dating when Sabatino’s pastor, Father Joseph Francavilla, asked him to consider a vocation to the priesthood after marriage. The priest informed Sabatino that the Eastern Churches, including the Melkite Catholic Church, have an ancient tradition of ordaining both married men and celibates and did not view the callings to priesthood and matrimony as “mutually exclusive.”

So Linda ultimately said, “Yes,” and, after 10 years of marriage, with five children between the ages of 1 and 9, she finally gave her “Yes” again: to the ordination of her husband, now-Father Sabatino Carnazzo and the director of the Virginia-based Institute of Catholic Culture. On May 1, Bishop Nicholas Samra of the Melkite Eparchy of Newton ordained him at Holy Transfiguration Church in McLean, Va., giving him the name “Hezekias,” where the Catholic congregation welcomed their new priest with shouts of “Axios!” (“He is worthy!”).

Linda, who homeschools the children, said the family has been preparing itself for this new chapter of their lives: The boys have learned how to serve the Divine Liturgy, and their daughter has been practicing the chanting.

But the new priest’s wife explained that just as with discerning the call to marriage, she also seriously discerned whether God was calling her to life as a clergy wife. Coming from a Latin Church background, she learned about the Melkite Church’s Eastern Catholic traditions while dating Sabatino and came to know Father Ephrem Handal and his wife, Judy, at Holy Transfiguration. Learning about their life and service to the parish was “eye-opening” for her.

“For me, I chose to say, ‘Yes’ to the whole package, which included this idea that my husband would be called to be a priest, and, therefore, I would be called to be the priest’s wife,” she said.

The vocation of the priest’s wife comes from the fact that the Catholic Church has both married and celibate clergy traditions among its 24 sister Churches that are in communion with the Bishop of Rome. In the Eastern Churches and in the Latin Church, only celibates can be ordained bishops, and priests can never marry after ordination.

Most of the Eastern Catholic Churches — with the exception of the Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara Churches — follow an ancient tradition of ordaining both married men and celibate men to the priesthood. In this tradition, ordained celibates live together in the monastery, while ordained married men, with their wives and families, serve a parish.

The Latin Church follows its own ancient tradition of ordaining only celibate men as priests, who can then live together in community with other celibates, as either diocesan priests (as exemplified by St. Augustine of Hippo and his diocesan clergy) or as professed religious or monastics.

Latin and Eastern-Catholic Priest Wives

But the majority of married priests and their wives in the U.S. actually belong to the Latin Church, not the Eastern Churches, which comprise only 1% of the U.S. Catholic population. Under Pope Pius XII, the Latin Church made an exception to ordain former Protestant married clergy to the priesthood, later setting down a structure with St. John Paul II’s “Pastoral Provision.”

Most of the priests in the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, created in this decade in response to Pope Benedict XVI’s 2009 apostolic constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus, are married men who had previously served in the Anglican and Episcopal churches. And many other Pastoral Provision married priests and their wives serve in parishes and dioceses across the U.S.

Lynn Grandon, for example, who serves as director of the Archdiocese of Denver’s Respect Life Office, is the wife of Father Douglas Grandon, who teaches homiletics at St. John Vianney Seminary and serves as parochial vicar of St. Vincent de Paul Church in Denver. He is also one of four national chaplains for the Catholic campus outreach Fellowship of Catholic University Students.

“We said, ‘Yes’ long ago, when our husbands felt the call to ministry from wherever we came from,” Grandon said, speaking of the perspective of wives of men ordained as priests through the Pastoral Provision. “So we knew what life was going to be like on most levels.”

For more than 20 years, she had helped her husband in his ministry that began as an evangelical pastor doing missionary work in Eastern Europe and then as an Episcopal priest, before they swam the Tiber with their younger children in 2003. As a priest’s wife, Grandon explained she finds herself often in the position of educating Latin Catholics about the Church’s married priesthood and banishing certain myths and misconceptions. Catholics in the pew quickly realize that having married men ordained as priests has nothing to do with heterodox positions like “women priests.” Indeed, Grandon explained that “progressive” Catholics become chagrined, and “conservative” Catholics become delighted, when they discover that her husband is a lion of Catholic orthodoxy and tradition in the pulpit and in person.

While the demands of Father Grandon’s vocation involves sacrifice, she said some Catholics make the mistake of thinking that the “family suffers.” Grandon has a medical background and said that she and her children have seen their husband and father a lot more than spouses and children of fathers involved in demanding areas of the medical field or other careers, such as the military, first responders and even some in the legal profession. Overall, she said, their family life is quite healthy.

“When we fell in love and decided to marry, I knew that I was continually going to have to give him back to the Church and not be selfish about it,” she said. “You have to give up selfishness 100%, 24-7, 365 days out of the year … and I happily do that — most of the time!”

Speaking from the Eastern Catholic tradition, Sarah Tamiian, whose husband is the pastor of St. John the Evangelist Romanian Byzantine Catholic Church in Los Angeles, agreed. Being a priest’s wife is a life of sacrifice that involves embracing the evangelical counsel of poverty to a degree, since the priest’s family will never be well off.

“What surprises me and other people is how normal our life is,” she said. She told the Register that her husband makes time to spend with their children, taking them fishing or playing tennis.

At the same time, her vocation also “takes a lot of flexibility.” The Catholic parish they serve has roughly 50 persons, and Tamiian explained that she sees her vocation as stepping in where there is a need and then handing the task over to a member of the church who wants to step in. Her older girls now help her with cantoring for the Divine Liturgy. The family helps put together the Mass books and the bulletin and maintains the church’s online presence.

“I sort of feel like we’re the water that comes to fill a void. The only times when I felt bad was when I didn’t anticipate a need,” she said.

Sometimes, she and her children accompany her husband on visits to the hospital or to the elderly, if people are open to it. She makes sure that his coffee mug is full and that he has a good breakfast before going to the hospital, where he serves as a chaplain.

Once, a three-day family getaway they had planned was cut short to one day, after her husband got a call that someone dying at the hospital needed the sacraments, and there was no other priest available. But she said such sacrifices help them appreciate the time they have together.

“It’s about looking at what you get, instead of looking at what you lost,” she said.

Marks of the Priest’s Wife

The Eastern Churches, both Catholic and Orthodox, have a rich depository of tradition, theology and iconography for the vocation of the priest’s wife.

Father Peter Galadza, acting director and Kule Family Professor of Liturgy at the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies at St. Paul University in Canada, told the Register that the vocation of the priest’s wife involves elevating her marital and maternal commitment to a higher spiritual level, which complements her husband’s spousal and paternal ministry to the Church.

But the Eastern Churches make clear that the vocation of the priest’s wife is not to be “an associate pastor” and certainly not a glorified “housekeeper.” Rather, the vocation of a priest’s wife is to share in the life of her husband, as he shares in her life and benefits from her example of sacrificial love and holiness.

Father Galadza, who himself is a married Byzantine Catholic priest, said the Church understands the priest needs to be held accountable in his ministry and is becoming even more cognizant of how that has to happen in the married and celibate contexts. For celibates, that accountability has to come from other priests who live with him. In the Eastern Churches, it is the wife of the married priest who helps hold him accountable. Father Galadza added that his wife, Olenka, has reminded him to return phone calls or make hospital visits.

“She has helped me consistently to sanctify, and be more committed in, my pastoral duties, and to be more humble,” he said.

The vocation of the priest’s wife, Father Galadza said, draws upon the example of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Theotokos, whose presence is felt and who tells Jesus Christ of parish needs. Another is the kenosis, or hidden action of the Holy Spirit. The Christic nature of the priest and the maternal nature of his wife correspond to St. Irenaeus of Lyon’s description of the Word and Spirit as “two hands of God.”

Eastern Catholic (and Orthodox) Churches have even denoted the priest’s wife with various titles that correspond to certain characteristics, such as her spiritual motherhood (pani matka or matushka, “little mother”); benefactress to others (dobrodiika); or as an elder (presvitera or presbytera), alongside her husband, the presviteros or presbyter).

And the vocation of a priest’s wife can manifest itself in a variety of ways, from the active to the non-active, as the needs arise. A married clergy only works, Father Galadza noted, when both spouses realize that the woman has a vocation that is united with her husband’s, even if it is largely hidden from view. Without his wife’s support, a married priest could not hope to succeed, either at his ministry or his marriage.

Two Lifetime Commitments

As a priest’s wife for more than 40 years, Irene Galadza knows how the vocation of a priest’s wife relies upon the lifeline of prayer and constant dependence on God. She helped her husband build their Ukrainian Greek Catholic parish of St. Elias in Brampton, Canada, watched it grow and thrive, and then burn down. Her house has now become the parish hall, while the church is being rebuilt.

“Just like marriage was a lifetime commitment, I realized this was a lifetime commitment,” she said.

“It is just amazing how God has sent us what we needed at the moment we needed it.”

Irene, wife of Father Roman Galadza and the sister-in-law of Father Peter Galadza, has taught classes on the vocation of the priest’s wife to women whose husbands are candidates for ordination. Just like Mary’s fiat was needed for God to come into the world, the bishop requires that the wife also discern her calling as a priest’s wife and give her fiat to her husband’s ordination. The wife is also getting formation to help her discern “with open eyes” whether she is called to take on the vocation of a priest’s wife and if the time is right, for her and the family for his ordination.

“Any clergy wife’s main job is looking after the family,” she said, explaining that the priest’s wife keeps her children spiritually and emotionally healthy and generally gets more active in parish activities as her children get older.

But the key for the priest’s wife is to have a deep, uncompromising faith in God and openness to the work of the Holy Spirit. Praying and having the help of a trusted spiritual father or mother (akin to a spiritual director) for counsel is essential, particularly in trials, she said. Keeping up her spiritual life allows her to guard and protect her husband’s and family’s spiritual health and well-being.

A priest’s wife’s vocation can take many forms. For some, it is a vocation mainly felt in the home; for others, it can be a vocation of presence in the parish, or take even more active forms, such as pro-life ministry, organizing retreats or teaching catechesis. But above all, Galadza said, she is a spiritual mother.

“Spiritual maternity is a most humbling and rewarding part of this unique vocation,” Galadza said.

Many times, women will come to her, rather than her husband, with very personal issues, such as suffering from miscarriage or marriage problems or the pain of a previous abortion, because they are more comfortable speaking to a woman.

“She just needs to be comforted, knowing that someone empathizes and understands,” Galadza said. She encourages other priests’ wives to have a bank of information at their fingertips for referring people to good Catholic doctors, therapists or social workers, should the need arise.

However, she said this is only complementary to her husband’s vocation. “If it is something more complicated, often I’ll say, ‘You need to talk with Father,’” she said, particularly if what that person needs is healing from sacramental confession.

Looking at the Saints

Priests’ wives also have the example of the saints to draw upon. Although their names are largely unknown to history, many priests’ wives accompanied their husbands into the Soviet gulags. And in Syria and Iraq today, they have also shared the burden of persecution with their husbands.

For Linda Carnazzo, one favorite saint is St. Anne, the mother of Mary. She also says there is St. Julianna, as well as St. Amelia, a mother of 10 who raised up three saints, including St. Basil the Great. She also has a devotion to Our Lady, the Theotokos, particularly under the title “One Who Makes the Rough Ways Smooth.”

“The nice thing about both marriage and the priesthood is that you don’t know exactly how the adventure will unfold until you say, ‘Yes’ with faith and trust in the Lord, and then it’s great,” she said. “In a good way, God has all sorts of surprises for you, challenges you never thought of, but he gives you the grace to meet them.”

Peter Jesserer Smith is a staff reporter for the Register.

- Keywords:

- catholic

- catholic church

- eastern catholic churches

- latin rite

- married priests

- peter jesserer smith