Black Bottle Man: A Novel for Nearly Everyone

This YA novel captures the imagination and makes you consider the nature of evil

Lately, I’ve been resisting the piles of books in my house.

I want something different. I want something good. I want something I haven’t seen before.

And yet, in the midst of this desire for novelty, I also have a desire for something tried and true, something I’m sure to like and enjoy.

As it happens, I was able to find something that suited me perfectly within the bounds of my own bookshelf, double-parked between piles of review books that may never move.

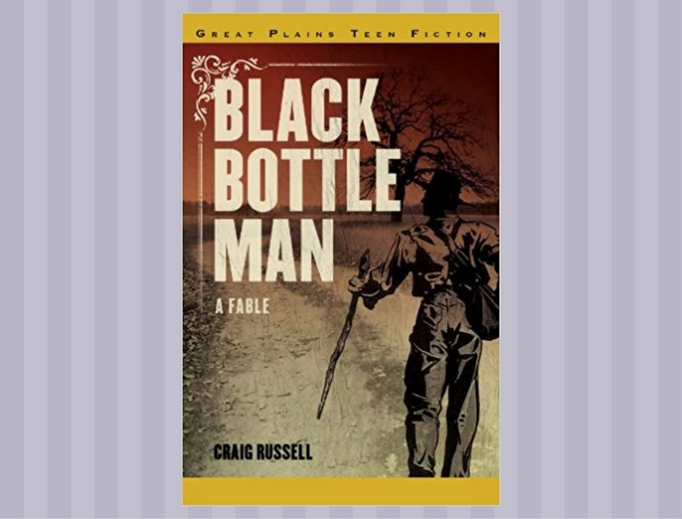

Black Bottle Man (2010, Great Plains Teen Fiction), by Craig Russell, was recognized in a number of ways after its release, including winning the 2011 Moonbeam Children’s Book Award and being selected as a title of “exceptional calibre” for the 2011 Canadian Best Books for Children & Teens.

But, honestly, none of that really caught my eye.

And the back cover blurb didn’t really capture my attention either.

The first chapter, though, hooked me in, and the rest was a blur as I curled up to finish it.

The book is told between time periods, mostly by one main character, Rembrandt. As you read the book, you come to realize what’s really happened (and I won’t spoil it by explaining too much here!) and why Rembrandt, his father, and his uncle can’t stay in one place for longer than 12 days.

I struggle to categorize this book: is it fantasy? Is it science fiction? Is it merely a good novel that I want to put into my daughter’s pile?

Yes, it is all of those things, to some extent. It’s also a book that flirts with ethics and religion, if only because it considers evil as a total and absolute. There’s no bargaining, there’s no gray, there’s no “maybe” or “what if” or “kinda sorta” about it.

Better than that, this is a book that is well-crafted and a story that is well-told. And, at the heart of it, isn’t that what we seek when we look for a good read?

I enjoyed getting to know Rembrandt, first as a 90-year-old man, then as a young boy, then as a teenager, and, interspersed between, as an old man. The varying points of view peppered the book with wisdom and insight, even as they also pieced the puzzle together for the reader.

This book also gave me a reminder of a farming era gone by, one that I haven’t read about since I last picked up Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. While Russell is not making the grandiose statements that Steinbeck’s been accused of (and nor does he write the monolithic novel; Black Bottle Man under 200 pages), he does write in and from the Depression-era farm life.

Here’s a taste, from the first chapter:

In five minutes Rembrandt celebrates his ninetieth birthday. Then he has thirty days to live.

Not that anyone here will be baking him a cake. It’s his first night at this shelter, but the Salvation Army folk are always good to him wherever he goes. Always good for a hot meal and a warm cot, but they have plenty on their plates already.

This Sally Anne dormitory stinks, but Rembrandt is used to the reek of unwashed bodies. In homeless shelters across Canada and the U.S. he has inhaled the musk of men who stumble through life, the sour odor of women too shattered to care. And before there were such things as homeless shelters, he’d shared shanties with hobos and migrant workers from Texas to Alaska.

For eighty long years, Rembrandt has been on the move. But he is not like the others in this cot-filled hall. He’s not a drunk, nor an addict, nor currently, a mad-man. Nevertheless, he moves on every twelve days. Sometimes sooner if a place offers too much of its own trouble. But he never stays longer than the twelve.

Like an Eleventh Commandment, “The Pact” has fixed that unrelenting time limit. It is part of a bargain that has ruled and ruined his family for four score years, a covenant forged from family pride and maternal desire. As unforgiving as an iron rod laid upon his shoulders, a burden at first shared with his pa and Uncle Thompson, but now carried onward by him alone.