‘I Did a Lot of Praying’: 97-Year-Old Veteran Recalls D-Day

Connecticut sailor gives firsthand account of Normandy invasion and casualties.

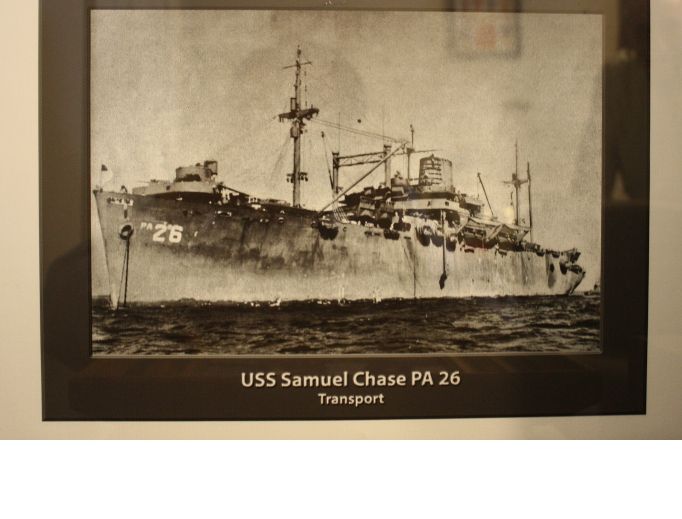

TRUMBULL, Conn. — Anthony Salce was aboard the USS Samuel Chase off Normandy Beach 75 years ago.

“We’d pray out loud, ‘Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee,’” he remembers. “The water was really rough.”

This June 6, Salce is among those veterans commemorating the events of that day 75 years ago that launched the major turning point in World War II, as tens of thousands of Allied forces in “Operation Overlord” landed on the beaches of Normandy on what was to become known as D-Day.

On that fateful June 6, 22-year-old Salce was one of the Samuel Chase’s crew who carried the first wave of soldiers to storm Omaha Beach. He would become a recipient of France’s Legion of Honor, in addition to other medals.

“We had the First Division aboard — one of the best divisions in the Army,” he recalled to the Register. Better known as the famous “Big Red One,” the division would suffer tremendous losses by midday, as they were a great part of the first troops off the landing boats to hit the beaches.

Aboard the Chase, there were “about 30 men” for each of the “32 Higgins boats” — the popular name for the landing crafts — that the ship also transported, Salce explained. Once they were launched, he watched the soldiers climb down the rope ladders into the landing crafts and then head to Omaha Beach. He could see lines of barbed-wire fences along the beach, ready to slow down the Allied assault.

The Chase was a U.S. Navy ship manned by the U.S. Coast Guard, which many people do not realize took part in many major naval operations and was an essential part of “Operation Neptune.”

The ship was one of the attack transports to land and support the troops. With soldiers of the Big Red One aboard, the Chase was assigned to the section of Omaha Beach code-named “Easy Red.”

“German bombers were coming and dropping their bombs, but they missed our ship,” Salce said, recalling the events of the day before D-Day. He added with a smile, “We were called the ‘Lucky Chase.’” The ship survived other perilous campaigns, too.

On D-Day the Germans on land were shooting at the troops, but the soldiers on Salce’s craft were out of range. He remembers how terrible it was to see how they “shot the guys in the boats” who were within range. It was also devastating, he said, to see the soldiers drowning because they were loaded down with equipment and the landing craft had to drop them off in water that turned out to be above their heads.

For example, an article in The Atlantic magazine described in just one instance how the first men out of one Higgins boat “are ripped apart before they can make five yards. Even the lightly wounded die by drowning, doomed by the waterlogging of their overloaded packs. From Boat No. 1, all hands jump off in water over their heads. Most of them are carried down. Ten or so survivors get around the boat and clutch at its sides in an attempt to stay afloat. The same thing happens to the section in Boat No. 4. Half of its people are lost to the fire or tide before anyone gets ashore.”

The article continued, “Other wounded men drag themselves ashore and, on finding the sands, lie quiet from total exhaustion, only to be overtaken and killed by the water.”

Modest Medal Recipient

Today, as an active 97-year-old, Salce is very modest about his medals, especially the Legion of Honor that France awarded him; in fact, he had humbly protested receiving the medal.

“I just did everything you had to do. I was protecting us. I just did my job. They should give medals to people who really deserve it,” he stated.

For the record, the Legion of Honor is the highest French order of merit, or decoration, given for both military and civil achievements. The Legion of Honor’s military criteria are for bravery or service and were given in one of the three main campaigns to liberate France, such as the Normandy invasion. The medal was established in 1802 and has five degrees or orders. Salce’s designates him as “a Knight.” The medal is shaped like a Maltese Cross, with five arms. One side of its center disc is inscribed with the Legion’s motto, Honneur et Patrie (“Honor and Fatherland”) and its foundation date on a blue enamel ring. The badge is suspended by an enameled laurel and oak wreath.

Salce was granted other medals, too, but he quickly turned the conversation back to the battle itself.

“It was a hell of a war,” he said, explaining that the Chase would remain in the Normandy area two days before heading back to port in Scotland. “Guys landing would come back and talk about what happened,” he said, mentioning that he himself went ashore only once.

“I did a lot of praying,” he emphasized. And not just on D-Day. “We had Mass every Sunday.”

On D-Day, Salce recalls how the smaller landing craft returned from shore carrying casualties, who were then treated by the Chase’s doctors and corpsmen. One of Salce’s strongest memories was seeing all the bodies being brought back to the ship. Heading to port in England from Normandy, he recalled, “We came back bringing bodies in sacks. They were piled up on the decks. I was crying a lot” over those heavy losses.

Duty Continued

Shortly after D-Day, Salce found himself and the Chase heading to the Pacific to bring “the Third Division to sweep the islands,” he related.

Records show that when the Chase was just off Okinawa, there were frequent air attacks by the enemy, but, again, “Lucky Chase” came through just fine.

Salce well remembers how they picked up troops and brought them to different locations, including to Japan once the Japanese surrendered. In fact, entering Tokyo Bay, the Chase was the first American warship to bring troops to postwar Japan.

“In the Pacific we picked up wounded Marines and headed with them to Hawaii,” he said. “On one of the trips we went aground. We were hung up for a day on a reef” before the ship was freed and actually floated again, but the big hole it suffered meant they had to sail to Hawaii for repairs and then push on to San Diego with a load of servicemen going home.

Later, in 1945, after three years of service in World War II, Salce came home, married, raised a family and became an active member of St. Theresa parish in Trumbull, Connecticut, where he has been a church trustee for many years.

Salce continued to do well into civilian life what he had done so often throughout the war — as others had too, as D-Day proved. Today, Salce still relies on divine Providence, much as he had on that sixth day of June in 1944 off the beaches of Normandy.

He concluded: “There was a lot of praying going on.”

Joseph Pronechen is a Register staff writer.