Catholics in the Crosshairs of Big Tech?: Recent Cluster of Cases of De Facto Online Censorship Raises Concerns

Lack of transparency from platforms makes intentional suppression an open question.

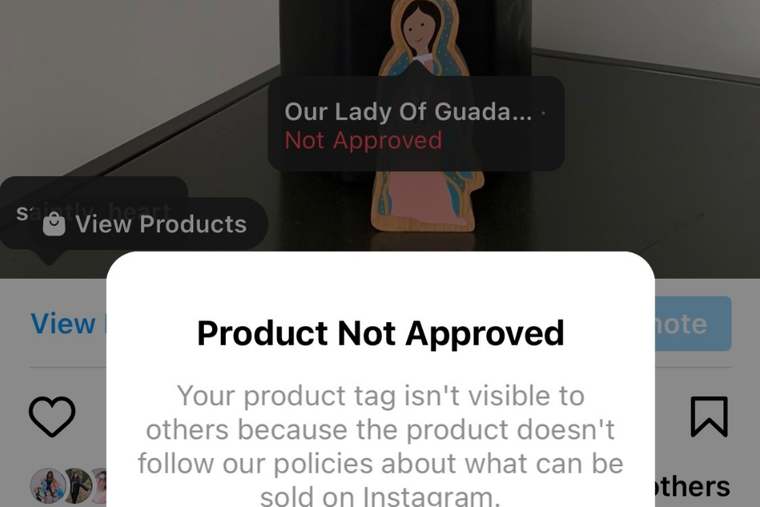

Saintly Heart is a small, online Catholic toy shop, which describes the wooden toys and temporary tattoos it sells as a “playful way” for kids to learn about the saints. Clearly, they’re not the type of outfit you’d expect to be selling “products with overtly sexualized positioning.”

Yet according to Instagram, that’s exactly what Saintly Heart did — so much so that owner Maggie Jetty received notice on Jan. 22 that a “tag” to one of her products had been removed from an Instagram post she had made more than a month previously.

The “overtly sexualized” product in question? A wooden figurine of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“I was shocked because I’ve never had any issues with Instagram or having a Catholic item on there,” Jetty told the Register, noting the irony that an image of the Patroness of the Unborn was flagged on the day when the Church specifically prays for the legal protection of unborn children.

Jetty immediately followed up with Instagram, submitting a request that the decision be reviewed. But, now, more than three weeks after the fact, she has yet to hear back, describing the Facebook-owned social-media platform’s system for managing complaints as “kind of like a black hole.”

On its own, what happened to Saintly Heart might be easy to dismiss as a “fluke” or a quirk of the algorithms used by social-media platforms to filter out offensive content. After all, Catholic items aren’t the only products that have been mistakenly tagged as “overtly sexualized.” A picture of Walla Walla onions in a wicker basket, for instance, received the same treatment from Facebook’s algorithms in October 2020.

However, a recent slew of similar instances of de facto censorship affecting Catholic businesses, organizations and individuals is renewing concerns about the possibility of Big Tech bias against Catholic and other religiously conservative viewpoints.

In addition to Saintly Heart, several other Catholic small businesses are reporting products being blocked on social media for ill-fitting reasons, often times months after the products had first been placed on digital markets without event. An ad for Just Love Prints’ “Rest in Him” vinyl sticker, for instance, was censored by Facebook because of its apparent “sexually suggestive manner.” Other companies have had images of saints flagged for promoting alcohol consumption, with alcohol in no way represented in the images.

Viewpoint Censorship

Other recent instances of de facto censorship seem less attributable to bizarre but unintentional algorithmic overreaches. The Catholic publisher TAN Books has faced social-media difficulties with a number of its products. Carrie Gress’ The Anti-Mary Exposed was pulled from a Catholic gift shop’s Instagram and Facebook accounts in January — nearly a year after it was first posted — after being flagged as an “adult product.”

TAN’s Facebook ads promoting Kimberly Cook’s Motherhood Redeemed and Paul Kengor’s The Devil and Karl Marx were recently pulled down, in the former’s case because of an alleged violation of the social-media platform’s “Sensational Content Policy” and the latter because of Facebook’s apparent policy to limit ads related to politics during the general elections, which were held months ago.

Perhaps most egregious of all, ads have also been pulled for Regina Doman’s Stations of the Cross, on the basis that the book’s cartoonized, non-gory depiction of the Crucifixion — perhaps the most iconic and widespread image in world history — contained “shocking, sensational, inflammatory or excessively violent content.”

In one of the most brazen and obvious instances of viewpoint censorship, the Twitter account of Catholic World Report (CWR) was suspended after the outlet tweeted a Catholic News Agency news brief describing Dr. Rachel Levine, President Joe Biden’s nominee to be assistant secretary of Health and Human Services, as “a biological man identifying as a transgender woman.”

CWR’s account was locked on Jan. 24 on the basis that the tweet in question violated Twitter’s rules against hateful conduct, purportedly for pointing out that Levine is indeed a biological male. On Jan. 27 Twitter responded to CWR’s complaint, confirming that “a violation did take place, and therefore we will not overturn our decision.”

On Jan. 29, Twitter reversed course and lifted CWR’s suspension, offering no clarification directly to CWR, but telling Catholic News Agency that “the enforcement action was taken in error and has been reversed.” But Carl Olson, CWR’s editor, pointed out that the shift only happened after the story began to spread, generating pushback against the social-media giant from the likes of the Catholic League and even secular sources.

“I would have to say No,” Olson said when asked if he thought CWR’s Twitter account would’ve been restored without widespread outcry. “I have to think that if nobody noticed it and we didn’t even mention it, and this just kind of went along, I think the account would have been [permanently] locked for not agreeing to remove the offending tweet.”

Olson said he wasn’t surprised that the offending tweet was initially labeled as “hateful,” given the totalitarian tendencies of transgender ideology, which treats any disagreement with its conception of human sexuality as a form of violence. He said this viewpoint is highly influential among Big Tech employees, well-documented to be far more progressive and nonreligious on average than the American public.

He said what CWR experienced is part of a wider pattern of post-election aggression from Big Tech platforms against those with opposing viewpoints.

“I think that’s really part of what’s going on,” Olson told the Register. “I think there’s a little bit of a kind of testing of what the response is,” when outlets are blocked or issued warnings.

Mary Eberstadt, the Panula Chair at the Catholic Information Center and a senior fellow at the Faith and Reason Institute, made a similar assessment. Writing for Newsweek, she suggested to President Biden that his “election has emboldened your liberal and progressive allies to target for ostracism and punishment a new band of ‘deplorables’: your fellow Catholics.” Eberstadt urged the president to “tell your progressive allies, and everyone else, that prejudice remains prejudice — even when it is aimed against people who did not vote for you.”

Lack of Transparency

There’s no denying the recent flux of Catholic voices and entities caught in the content filters of Big Tech platforms, but does this series of anecdotes necessarily indicate deep-seated, systemic bias against Catholics and other conservative viewpoints in the way these companies moderate content, perhaps even baked into their algorithms?

It’s hard to say, says Rachel Bovard — which is a big part of the problem.

“Because there is no transparency, the terms [of enforcement] are so vague, and there are no actual details about how Big Tech’s algorithms actually work … we’re just kind of left scratching our head,” Bovard, the senior director of policy at the Conservative Partnership Institute, told the Register.

Bovard, who also serves as a senior adviser to the Internet Accountability Project, testified on Big Tech bias before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law in October 2020. The lack of transparency regarding Big Tech’s decision-making about content moderation and the way their algorithms work means denials of bias are just as unverifiable as accusations, she said.

Bovard’s testimony cited Mark MacCarthy, a senior fellow at the Institute for Technology Law and Public Policy at Georgetown University, who suggested that Big Tech could dispel accusations of bias by allowing researchers to examine their internal practices related to system-wide algorithmic and content moderation — a suggested solution that Bovard noted no company has pursued.

Speaking to the Register, Bovard suggested that the lack of transparency is intentional, allowing progressive social-media giants to aggressively moderate content that violates their political commitments behind a veil of vague community standards. A prominent recent example was the suppression of an October New York Post article alleging that then-candidate Biden was involved in his son Hunter’s business dealings with foreign energy companies. The Post’s Twitter account was initially locked on the grounds that its story was based on illegally obtained information, a standard inconsistently applied across the platform.

Another recent high-profile case was the permanent ban of former President Donald Trump from Facebook and Twitter for allegedly inciting the violent riots that took place at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, a move that the tech giants haven’t taken with other world leaders, such as Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who has called for violence against Israel.

Consequences and Remedies

Even without access to their internal practices, Bovard said there is “ample evidence” that Big Tech platforms engage in viewpoint bias. Given the de facto level of control these companies exert over access to information and the public conversation, she said the regime of censorship exercised by social-media giants represents a threat to a free society and even to religious people’s ability to witness in the public square. “When other people’s viewpoints are taken away, our ability to evangelize is limited; our ability to persuade is nonexistent,” said Bovard, a Catholic.

Although companies like Facebook, Twitter and Google are privately owned, Bovard contended government intervention is justified for two reasons. One, she said Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a measure that provides social-media services with immunity from civil liabilities from content posted to their platform, is “tantamount to a subsidy,” making these companies “privileged First Amendment actors” in a way that movie studios, newspapers and other publishers can’t be without repercussions.

More importantly, Bovard suggested, these private companies’ ability to influence the wider conversation represents a legitimate public concern.

“So it is totally appropriate for the government to step in and say, ‘No, Big Tech, you don’t get to decide how we live together. You don’t get to decide what information we can access. That is what we [as a society] decide.’” Bovard added that government intervention in such a scenario is perfectly consistent with the conservative understanding that government has a legitimate, albeit limited, role to play in conserving free society.

In terms of remedies, Bovard and other Catholics, like former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum, expressed concern about repealing Section 230 protections outright, suggesting it might give a government controlled by progressives unprecedented power to censor conservative speech online.

Instead, she recommended greater enforcement of federal antitrust laws, which prohibit predatory industry monopolies, a designation she believes fairly applies to Big Tech platforms like Facebook and Twitter, especially with the recent suppression of alternative platform Parler from the marketplace.

“We don’t give amnesty for other lawbreakers,” said Bovard. “Why do we give amnesty for Big Tech? They’re breaking the law.”

Enforcing antitrust laws against Big Tech wouldn’t necessarily mean forcibly breaking up the companies concerned. Bovard said the government could also pursue “behavioral remedies,” which would limit Big Tech companies’ abilities to use their enormous financial resources to limit competition in the marketplace. An example of one behavior that could be checked would be Google’s ability to pay exorbitant amounts of money to make itself the primary default search engine on phone and web browsers, effectively boxing out the competition.

Questions of Big Tech oversight are expected to come up before Congress this session, with considerable bipartisan support for the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act. Another proposal, the Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Act of 2021, would offer far more sweeping reform of U.S. antitrust law.

Engaging in the Public Square

For some Catholics, the escalation of potential Big Tech censorship of conservative religious viewpoints is not only unsurprising; it’s an indication that Catholics should look elsewhere for platforms to share their views.

Register blogger Matthew Archbold, who also blogs at CreativeMinorityReport.com, said Catholics made a mistake by abandoning blogs for social-media platforms over the past decade. Recent difficulties with social-media platforms may be the catalyst for a return to blogs, which he contended are a more human and less impulsive way of communicating on the internet.

“I’m not saying we should log out from Facebook or Twitter completely,” Archbold recently wrote for the Register. “But I also think blogging your well-reasoned thoughts or sharing your real-life experiences is far better than hot takes. A blog post can go in depth whereas a tweet is so limited.” Bovard, however, said such retreats could become a “ghettoization” of Christian witness and says that Catholics should be “proclaiming the truths in the Gospel very loudly and wherever we can.”

“As religious people, we have just as much of a right to the public square as everyone else,” she said. “And in America, the greatest country in the world that was founded on pluralism and freedom of expression and freedom of religion, that is something that we should fight for.”

For his part, Olson of Catholic World Report took a both/and approach. While some Catholics might have a particular calling to be engaged in social media as an apostolate, he said this isn’t necessarily a requirement of everyone. Additionally, he urged Catholics who do feel called to engage on social-media platforms to consider the potential spiritual costs — not only political and social ones — and suggested that others should be exploring “creative ways of doing our own thing.”

Jetty at Saintly Heart pointed to the irony of social-media giants essentially “deplatforming” the saints by limiting her business’ outreach, given that social networks tend to promote all sorts of secular lifestyles with little in the way of restriction. She said her desire to provide a more compelling example to young people today is one of the primary reasons she started Saintly Heart. And because of that, she said she’ll continue to market on Facebook and Instagram, to the extent that she’s able.

“Our kids need good role models,” she said. “They need to learn about the faith younger, because they’re learning a lot about life on social media, and it’s not a great place for them.”

- Keywords:

- censorship

- big tech

- jonathan liedl

- saintly heart

- maggie jetty

- amazon