Cardinal Robert Sarah Discusses the Sublimity of Silence

The Power of Silence, co-written with Nicolas Diat, was inspired by the Carthusian monastery at La Grande Chartreuse.

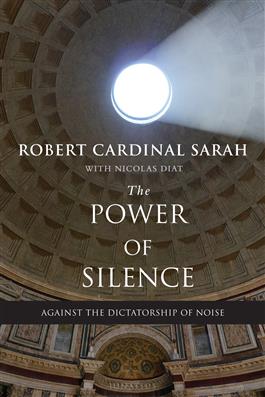

Cardinal Robert Sarah, the prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, is the co-author, most recently, of The Power of Silence: Against the Dictatorship of Noise (Ignatius Press).

Inspired by the daily rhythms of sacred worship and contemplative prayer at La Grande Chartreuse, the historic Carthusian monastery in the French Alps, Cardinal Sarah and co-author Nicolas Diat reflect on God’s self-disclosure through the silence of the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, Easter and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.

During a written exchange with Register Senior Editor Joan Frawley Desmond, the African cardinal explains how ordinary Catholics can become contemplatives in the world, and he warns that those who live under the “dictatorship of noise” will shut out the “humble voice” of God.

Your new book, The Power of Silence, is grounded in a dialogue with the prior general of the Carthusian Order, Dom Dysmas de Lassus, based at La Grande Chartreuse in the French Alps. What brought the prefect for the Congregation of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments to the monastery?

As prefect for the Congregation of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, I wished to see firsthand the specificities of the Carthusian liturgy, slightly different from the Roman rite. On a more personal basis, since I wanted to write a book about silence, I deemed it useful to go to the most silent place in the Catholic Church. La Grande Chartreuse is an absolute desert of silence. All the surroundings of deep solitude, the beauty of the mountains, the mysterious austerity — in a word, the entire environment seems to be God’s dwelling.

One could say: “Truly, the Lord is in this place! How awesome is this shrine! This is none other than the abode of God, the gateway to heaven” (Genesis 28:16-17).

I really wanted to experience the silence, the solitude and the presence of God in this sacred place of La Grande Chartreuse and to live and pray with the holy monks, especially the most impressive part of the monks’ life: “While the earth is sleeping, or trying to forget, the nocturnal Divine Office is the burning heart of Carthusian life,” as Nicolas Diat rightly underscores. It starts at a quarter past midnight and lasts nearly three hours in the darkness.

The silence of the Carthusians is based not only upon their not chattering together or with people from the outside without special permission from their superior; they lead also, all day long, an eremitical life, in separate little houses, having only some prayers and Masses in common in choir, the rest being individual. Their silence is also an effort to empty their memories and imagination from all the “garbage” stocked in them during their lives before becoming monks.

Last but not least, their silence also consists in not leaving any traces of themselves: They do not sign the books they (seldom) happen to publish, and they are buried in an anonymous tomb.

Thanks to that everlasting silence, they are able to listen to God’s Word, in the reading of the Bible, in the Divine Office and in their mental prayer. In return, they are not hindered by outside noise (no TV, no radio, no newspapers, no internet) in order to pray intensely for the whole world.

At the bedside of Brother Vincent, a Carthusian monk who died a painful death from multiple sclerosis, you confronted the mystery of God’s silence in the face of incurable illness. What did you learn?

My link with Brother Vincent started when I learnt he was offering up to God all his sufferings to obtain from God for me the graces necessary for the correct fulfillment of my ministry in Rome. The most sublime expression of love is suffering and dying, that is, the silent and total offering of our life. Brother Vincent used to say, “I believe that suffering is granted by God to man in a great design of love and mercy.”

Nicolas noticed that in Brother Vincent I soon “recognized an ardent soul, a hidden saint, a great friend of God.” This friendship was born in silence, it grew in silence, and it continues to exist in silence. [Quoting the book] “Brother Vincent was incapable of uttering a simple sentence because the sickness deprived him of the use of speech. He could only lift his gaze toward” me. He showed us that the silence into which illness had plunged him allowed him to enter ever more deeply into the truth of things.

My experience was that, despite that painful situation, Brother Vincent remained serene, joyful and patient. God asked him to be an ongoing holocaust and a silent offering for the world’s salvation; next to my friend, I became a pupil, learning the mystery of suffering.

Watching Brother Vincent, age 38, confined to his sickbed, silently revealed to me that “suffering is for the soul the great worker of redemption and sanctification,” as he had written in his personal journal, which I discovered on the eve of his burial.

How do you define silence, and what is the difference between exterior and interior silence?

In the negative sense, silence is the absence of noise. It can be exterior or interior. Exterior silence involves the silence of words and actions; in other words, the absence of noise from doors, vehicles, jackhammers, airplanes, the noisy mechanism of cameras, often accompanied by dazzling flashes, and also that horrible forest of cellphones that are brandished at arm’s length even during our Eucharistic liturgies.

As for interior silence, it can be achieved by the absence of memories, plans, interior speech, worries. Still more important, thanks to an act of the will, it can result from the absence of disordered affections or excessive desires.

Dom Dysmas rightly underlines: “Being silent with our lips is not difficult; it is enough to will it. Being silent in our thoughts is another matter. … Paradoxically, exterior silence and solitude, which have the objective of promoting interior silence, begin by revealing all the noise that dwells within us.”

True silence is not mere passivity, but a positive reality which leads to encounter and communion.

Your book ponders the silence of the Incarnation. Why did Christ come in silence and live most of his life in silence?

When you speak in a low voice, only people who are silent around you can hear you. God is a discrete lover — he is a silent and humble lover — and does not want to impose himself upon our freedom.

In coming silently into this world, he wanted to show that his relationships with us were to be free. He didn’t want to crush us like a dictator; but on the contrary, he wanted to make us free from the slavery of sin and from the tyranny of the devil. To do so, he acted humbly, the exact opposite to the pride of Satan.

That is why I cited the Book of Wisdom: “While gentle silence enveloped all things, and night in its swift course was now half gone, your all-powerful word leaped from heaven, from the royal throne” (18:14-15). Later on, this verse would be understood by the Christian liturgical tradition as a prefiguration of the silent incarnation of the Word in the crib in Bethlehem. Now silence is a part of humility.

Though being God, the Logos wanted to humiliate himself, giving up for some years the glory due to him, and becoming like a slave, dying like a culprit on a cross, for our salvation. Being the Word of God, he expresses eternally what God is, and in coming into this earthly world, he had to express also this discreteness, in using silence to say it. The silence of the crib, the silence of Nazareth, the silence of the cross, and the silence of the sealed tomb are one. They are silences of poverty, humility, self-sacrifice and abasement, self-emptying (Philippians 2:7).

When you reflect on the “silence of the cross,” you ask readers to “learn to stand silently at the foot of the cross while contemplating the Crucified Lord as the Virgin Mary did.” What is the Marian path of silence?

The entire life of the Mother of Jesus is bathed in silence.

In our book, I have tried to summarize this Marian path of silence with the words of Father Maurice Zundel: “Mary grants a hearing to the silent Word. Her flesh then can become the cradle of the Eternal Word. … In her, each man sees himself called to the same destiny: He becomes a dwelling of God, of the silent Word.”

St. John Paul II tells us that Mary’s journey — from the wood of the crib to the wood of the cross — was marked by “a kind of ‘veil’ through which one has to draw near to the Invisible One and to live in intimacy with the mystery” (Redemptoris Mater, 17). What is it that kept the Blessed Mother silent after her last words at the Wedding of Cana — “Do whatever He tells you” (John 2:5) — to the foot of the cross and through to her glorious assumption into heaven?

As the soldier thrust his lance through Jesus’ side, the sword of suffering pierced her heart, too. Mary stood before the atrocious sufferings of her son. She watched his unthinkable defeat and the apparent victory of Satan. She might have been tempted to flee from the cross or invite Jesus, as the Son of God, to climb down.

The Marian path of silence is this: to keep in one’s heart God’s word and ponder it. St. Luke tells us: “Mary kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 11:21). Not that she had full comprehension of all that she held and pondered in her heart. Rather, she consents to God’s “unsearchable judgments” and “inscrutable ways.”

Her greatness lies in her faith in God’s word, God’s promise by which she was willing to go forward with a plan she did not understand, to a place she had not chosen, for the sake of a people who would reject and torture and kill her son.

Finally, you discuss “the silence of Easter.” You say the grace of Easter is “a profound silence, an immense peace and a pure taste in the soul. It is the taste of heaven, away from all disordered excitement.” Is this the silence of the Eucharist?

Yes. I am struck always by the homily of Bishop Melito of Sardis in the Office of Readings on Easter Saturday as the Church Universal awaits the great vigil of Easter: “Something strange is happening — there is a great silence on earth today, a great silence and stillness. The whole earth keeps silence because the King is asleep. The earth trembled and is still because God has fallen asleep in the flesh, and he has raised up all who have slept ever since the world began. God has died in the flesh, and hell trembles with fear.”

It is imperative for us to rediscover the Easter we celebrate in each of our Eucharists. We must rediscover the urgency and importance of celebrating the Eucharist in silence: the silence of Easter.

Paschal vision does not consist in a rapture of the spirit; it is the silent discovery of God. If only the Mass could be, each morning, what it was on Golgotha and on Easter morning!

Remember that the Resurrection of Christ itself on Easter morning was seen by no one and was made in silence. The sound of Christ’s resurrection is not one of trumpet blasts and cymbal crashes, but, like the Introit chant of Easter morning, is a tranquil, mystical ascent from death to life. Easter marks the triumph of life over death, the victory of Christ’s silence over the great roar of hatred and falsehood.

Your book warns of the “dictatorship of noise.” Is this a new problem, and how can we overcome it while living in the world?

Blaise Pascal in the 17th century already noticed our tendency to look for diversions away from the essential truths. But modern existence is a propped-up life built on noise, artificiality and the tragic rejection of God, combined with an implacable hatred of silence. Dom Dysmas wonders “whether the voice that the modern world seeks to stifle with incessant noise and movement might not be the one that tells us: Remember that you are dust and that you will return to dust.”

In order to learn to keep silence and to nourish it with the presence of God, we should develop the practice of lectio divina, which is a moment of silent reading, listening, contemplation and profound recollection in the light of the Spirit, in front of the Bible and its interpretation by Tradition. Even people living in the modern world can take time to read the Bible and meditate silently upon it, at least during the liturgy.

You speak of the “silence of the eyes” and the “silence of the heart.” Would you explain what these terms mean and how they guide our efforts to be more present to God?

For some years now, there has been a constant onslaught of images, lights and colors that blind man. His interior dwelling is violated by the unhealthy, provocative images of pornography and violence. The silence of the eyes consists of being able to close one’s eyes and cast out these horrific and corrupting images in order to contemplate God who is in us, in the interior depths of our personal abyss. It is necessary to stop one’s ears too, because there are sonic images that assault and violate the purity of our heart, our sense of hearing, our intellect and our imagination.

Silence of the heart means to keep quiet inside ourselves, mastering our various fleeting desires, memories and fantasies, to keep them under the lordship of Christ.

Has the dictatorship of noise also tainted our celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass?

In many cases, the media have invaded the Mass and transformed it into a spectacle, when actually it is the Holy Sacrifice, the memorial of the death of Jesus on the cross for the salvation of our souls. Today, some priests have a tendency to transform the Eucharist, “the great mystery of faith,” into a vulgar country fair. It is also sad to hear occasionally priests chattering incessantly in the sacristy, and even during the entrance procession, instead of recollecting themselves and contemplating in silence the mystery of the death of Christ on the cross, which they are preparing to celebrate. Just think of the silence of St. Joseph.

I like very much what Pope Francis said recently about his silence. St. Joseph, the Pope noted, is a man “who can tell us many things, but who does not speak,” “the hidden man,” “the man of silence,” “who has the greatest authority in that moment without letting it be seen.” All he is focused upon is being the Guardian of the Redeemer of mankind (homily, March 20, 2017).

So the counsel of St. Charles Borromeo to priests regarding recollection is very apropos: “If a tiny spark of God’s love already burns within you, do not expose it to the wind, for it may get blown out. Keep the stove tightly shut so that it will not lose its heat and grow cold. In other words, avoid distractions as well as you can. Stay quiet with God. Do not spend your time in useless chatter.”

Holy Mass is the most sacred, divine thing. It must be surrounded with dignity, silence, intimate and silent adoration, and a sacral character. To rediscover this, it is necessary to use the various times of silence which are specified in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal of Blessed Paul VI, revised in the year 2002 by St. John Paul II. Liturgical music also must lead to silent contemplation rather than stir up passions that create noise and unrest in the soul.

What is the role of silence in sacred worship, and why must it be a fundamental part of the Church’s sacramental life?

In June 2012, in his homily for the feast of Corpus Christi, Benedict XVI solemnly declared: “[Christ] did not abolish the sacred, but brought it to fulfillment, inaugurating a new form of worship, which is indeed fully spiritual, but which, however, as long as we are journeying in time, still makes use of signs and rites. … Thanks to Christ, the sacred is truer, more intense and … also more demanding.”

Without radical humility, expressed in gestures of adoration and in sacred rituals, no friendship with God is possible. True Christian silence becomes sacred silence as it becomes silence of communion. This is why silence is necessary for a true sacramental life: It leads to adoration, to a personal encounter with the Living God. Before the divine majesty, we are at a loss for words. Who would dare speak up in the presence of the Almighty?

You applaud the role of Gregorian chant in sacred worship and explain that it “is not contrary to silence. It has issued from it and leads to it.” How does it foster interior silence?

With Gregorian chant, we enter into a sacred dimension, into a celestial liturgy, at the threshold of purity itself. Its musical form does not excite, but quite the opposite, it calms down the senses.

Here, music, by its expressive character, by its ability to convert souls, causes the human heart to vibrate in unison with God’s heart. Here, music rediscovers its sacredness and divine origin. Gregorian chant is, however, more than merely sacred sound. It is a musical form that makes the Logos, the eternal Word of God, incarnate in our midst by setting to music the words of sacred Scripture and of the liturgy itself. The chant tradition is a sung form of lectio divina, which I spoke of previously. Its aim is union with Christ.

Because of this twofold character, in which chant both fosters interior silence and opens the soul to an encounter with the living Word of God, Gregorian chant is rightly considered the “supreme model of sacred music” (Tra le Sollecitudini, No. 3; John Paul II, Chirograph, No. 7, 12).

It is a positive reality that many monasteries have kept the treasure of Gregorian chant, and many associations in the world are working actively and effectively for the revival of Gregorian chant, also sung by the liturgical assembly. Gregorian chant should be taught again in seminaries.

A good confession is surely the fruit of interior silence. But you observe that many Christians are no longer “willing to go back inside themselves so as to look at themselves and to let God look at them.” Is this why we resist silence?

Yes, I insist: Too few are willing to confront God in silence, by coming to be “burned,” tested with fire in that great face-to-face encounter. You speak of the sacrament of reconciliation and penance.

Now, the importance of interior dispositions and the necessity of reconciling ourselves with God, by agreeing to let ourselves be purified by the sacrament of confession, are no longer in fashion today — even before receiving holy Communion. Only through silence can we humbly acknowledge our sins. Remaining in silence reveals ourselves to ourselves, like a mirror.

You reflect on the power of silence in personal relationships: “The silence of listening is a form of attention, a gift of self to the other.” How can silence foster personal communion?

Dom Dysmas shows this in our dialogue with a beautiful comparison: “As long as there are lovers on earth, they will seek to see each other alone, and silence will have a part in their encounter. … The silence of a couple who are dining alone can express the depth of a communion that no longer needs words; [it] is a silence of communion; [it] says: I love you. … How is this message transmitted? By looks, by gestures, and by the heart. In this book, it goes without saying that we wish to speak about the silence of communion and about the riches it brings. Nevertheless, even within this silence, there is a great diversity. A person can keep quiet in order to listen and to receive everything conveyed by the other’s silence. He can keep quiet in order to say in some other way what does not belong to the language of words or because he is facing a reality that is too imposing to speak about.”

Political and social change has stirred anxiety about America’s future, sparking passionate, often angry debate and more activism. In contrast, you offer silence as “a mysteriously effective hidden instrument” in times of crisis. What do you mean?

How did the gulags of the Soviet Union fall? By the silent prayer of St. John Paul II and of the entire Church, sustained by Our Lady of Fatima, especially the silent prayer of all those who were prisoners of the gulags because of their faith in God. Sophisticated political strategies did not get the better of Marxist communism.

Prayer had the last word. The silence of the Rosary obtained the unthinkable.

Throughout The Power of Silence, you return to the testimony of St. Teresa of Calcutta, who said: “The more we receive in silent prayer, the more we can give in active service.” How does contemplative prayer nurture a deep love for the poor and clarify the work of social justice?

For St. Mother Teresa, all is born from silence. [She wrote:] “The fruit of silence is prayer. The fruit of prayer is faith. The fruit of faith is love. The fruit of love is service. The fruit of service is peace”; [and] “In this silence, we find a new energy and a real unity. God’s energy becomes ours, allowing us to perform things well” (In the Heart of the World).

When praying silently, we open our hearts, our souls, to the invisible action of the grace of God, which transforms us and gives us enough light and strength to take care of our fellow human beings, especially those for whom we must imitate the special care of God: children (especially the unborn in the womb of the mother), the poor, the disabled, and so on. Without Christ’s grace, we are simply not able to get out of our selfishness and love our neighbor as ourselves.

The vast, infinite majesty and mystery of God inspires awe and fear in his human creatures. How does God make it possible for us to know him, and can you share a moment captured from your own path of interior silence?

God made it possible to know him through his Son, the Word Incarnate, our Lord Jesus Christ, who said to the apostle Philip: “Philip, he who has seen me has seen the Father” (John 14:9); 1 John 1:2-3 also expresses how Jesus reveals God to us. It is explained in a more lengthy way in the conciliar constitution on divine revelation, Dei Verbum (4), about Christ, the plenitude of Revelation.

God, the Creator of the billions of galaxies, became a baby in the crib of Bethlehem, without any appearance of majesty. Who would fear a baby lying in a manger?

You see again how God acts, how discrete and delicate and humble he is with us. Humility and majesty, infinity and poverty, grandeur and loving proximity are perfectly blended in God, as we can see in Jesus Christ.

We owe him everything and should worship him with deep adoration and respect; at least before the Last Judgment, on his side, he is just tiptoeing into our lives. Just see how hidden, silent he is in the Blessed Sacrament of the altar! God is really amazingly great in his love for us. This is why we must kneel and adore him and love him with all our heart, with all our being, with all our strength, and with all our mind.

About my own path, I do not wish to add anything but this: At the Grande Chartreuse, it was a moving experience to chant with the monks, in the half-light of the evening, the great Salve Regina at Vespers! The last notes die out one by one in a filial silence, enveloping our trust in the Virgin Mary.

This experience is essential for understanding Joseph Ratzinger’s reflection in his book A New Song for the Lord: “Silence … lets the unspeakable become song and also calls on the voices of the cosmos for help so that the unspoken may become audible.”