Promoting Peace: Crèches Show The Faith Is Universal

Knights of Columbus Museum Nativity Scenes Showcase Global Culture

NEW HAVEN, Conn. — Ever see a Nativity scene set in Louisiana bayou country? Or from a northern Peruvian village and carved from the calabash tree’s fruit? Or a tiny one in a miniature bottle and another painted on a large feather?

A number of unusual and eye-catching crèches and Nativity scenes range from these examples to larger pieces of artistry at the Knights of Columbus Museum in New Haven, Connecticut.

The theme of the 13th-annual crèche show is “Peace on Earth: Crèches of the World.”

This year’s displays showcase how the Prince of Peace has touched hearts globally.

Before visitors go to the main exhibit on the museum’s second floor, they’re greeted by two very different representations. One consists of striking, tall Zimbabwe stone Nativity figures that are a hallmark style of one particular tribe and carved from springstone native to the country. The other is a sprawling Neapolitan crèche, huge in dimension and elaborate in style.

Dozens of characters fill a 17th-century Neapolitan town that becomes the scene of the birth of Christ, which takes place on a hillside. Some locals find their way to the Holy Family, while many others are oblivious of this life-changing event, going about their usual routine: working, cleaning, dancing, eating outdoors, tending sheep or selling fish, fruit and vegetables. One vegetable stand shows corn cooking in a pot. The costumes and the fine facial expressions reveal each figure’s character, bringing the scene to life.

Up in the main galleries, the rest of the 70 scenes unfold, coming from the United States, Central America, South America, Eastern and Western Europe, Australia and Asia.

One favorite is the crèche with the Holy Family, visitors, camel and sheep from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, using 1930s chocolate molds from Dresden, Germany. The chalkware figures — no confections in this exhibit! — are attractive in their polychromed soft colors and early 20th-century look.

Another Nativity from Pennsylvania immediately catches the eye because it’s an all-aluminum scene made at the oldest forge in the United States. While this one has a monotone air of peace about it, another nearby scene virtually jumps out to grab a visitor’s attention: It’s a Nativity scene from Louisiana that springs from Cajun culture, taking one unexpected turn after another. Baby Jesus rests in a bayou canoe for a manger, as Mary wears traditional Acadian attire, Joseph holds a tray of crawfish, and a raccoon and alligators stand in for sheep. There’s also a Louisiana chef on hand.

Surprises of all different sorts are abundant throughout the exhibit. One is the “Christmas Pyramid,” a style developed in a section of eastern Germany. Built in three tiers that are turntables, the scene revolves as heat from candles at its base turns a propeller at the top, which allows the entire scene to keep revolving.

Also from Germany is an eye-catching Nativity set put together with mid-century Hummel figurines.

From Poland comes a towering szopka, a crèche form started in Krakow. This crèche is a four-story castle, with towers and intricate details, fabricated of aluminum foil, paper and wood. It shines with so many details that one must look carefully to find Baby Jesus among them. Another Nativity placed on several levels is a smaller example for Portugal. It grabs attention for being arranged on three tiers, with everything in neat rows, and painted in colors native to the area.

Among the crèches from Africa, one stately example comes from Burkina Faso. The figures formed in bronze are all tall and upright, fittingly reflecting the country’s name (“honest people”). Some details reveal European inspiration, possibly from missionaries, such as Mary’s veil and Joseph’s staff.

There’s also the tall yet simple figures of the Holy Family that make up an entire scene from Kenya, in which the Holy Family wears the traditional bright dress of the Maasai people. Another from Kenya is fashioned from a gourd and materials like straw, banana bark, wire and rubber.

Then come the wooden figures from Japan and China. China’s showcases a trio of triptychs, with fine details intricately carved in wood left unpainted, but with a soft glow, as the Holy Family finds shelter under a pagoda. God the Father also appears in this scene.

On a different plane, the quite large triptych from Vietnam is a lovely, serene Nativity scene done in lacquer painting, which is a fine art in that country. The figures show a strong European influence, most likely from the country’s past French colonialism.

From Ecuador comes a simple three-figure Nativity, with Joseph wearing a traditional poncho and fedora. Crèches also come from Egypt, Laos, Mexico, Jamaica, Brazil, Italy, Iceland, Belarus and more, reflecting local customs and using local materials.

The different interpretations show that “various cultures and tribes and peoples have claimed the incarnation of Christ for their own, using their own material. It belongs to them,” Father Timothy Goldrick says. An authority on crèches, he donated a number of them in this exhibit to the museum’s permanent collection.

During that same conversation, he also highlighted how the Council of Trent in the 16th century encouraged crèches be set up in churches and homes as acts of piety and catechetical tools. They teach no less today than they taught many centuries ago, going back to St. Francis in the 13th century.

Pope Benedict XVI’s comments to artists from 2009 put this show’s folk and fine art into perspective. He said, “The great biblical narratives, themes, images and parables have inspired innumerable masterpieces … just as they have spoken to the hearts of believers in every generation through the works of craftsmanship and folk art, that are no less eloquent and evocative.”

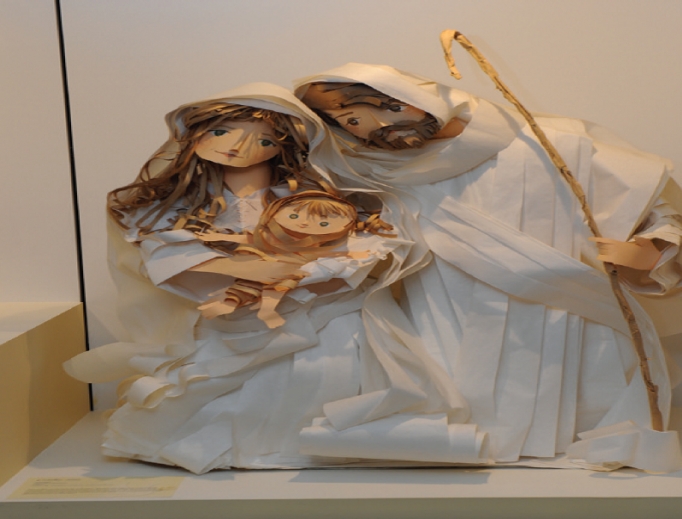

Particularly evocative is the new display of a huge Mexican replica of a Baroque set made for the Vatican a few years ago. This work of fine art, all hand-carved, with exceptionally intricate costuming, reflects Baroque Neapolitan styles with its more-than-three-foot-tall figures.

And the wonderful Nativity from Israel overflows with a catalog of ornate details. Formed mostly from dazzling mother of pearl and abalone, it displays not only the crèche, but also other events from Christ’s life, from the Annunciation to the Last Supper and then the Resurrection. It was a gift to St. John Paul II, who then donated it to the Knights of Columbus.

When visitors see these scenes, said Peter Sonski, the museum’s education/outreach director, “They come to appreciate the universality of Christianity and that Christ was born for all people in all times.”

Joseph Pronechen is a Register staff writer.

INFORMATION

KofCMuseum.org

The show runs daily through Feb. 19.