Why Do You Want to Hide Away Your Cross?

Growth and glory come through suffering and no other way.

For five very happy years, I was assigned to a great parish in Queens, New York — Saint Helen’s, built in 1979. Like many things build in the 1970s, myself included, it is very much a product of its day. Since I have left the parish, there have been two beautiful renovations, one in 2006 and another in 2017, each more beautiful than the last.

The parish Church was based upon a church the then-pastor had visited in Arizona and was seemingly dropped into the middle of Queens.

From the outside, as one would drive by it from the Belt Parkway in New York, one would think that it was a Pizza Hut or a ski lodge.

From the inside, the parallels with the ski lodge were even more striking. There was burnt sienna wall-to-wall carpeting, a stucco altar, a tabernacle on the far side of the church, few statues in the church at all (and the ones that were there were unpainted), and a giant bronze resurrected Jesus on the wall. There was no crucifix anywhere in the church. When the cross was carried in procession to the sanctuary, the custom was to place it away in the sacristy.

With all that being said, I could think of no better start in priestly life than the parish. It was busy sacramentally and it was a vibrant community. Truly, it was a joy to be present at this parish, where I served as parochial vicar.

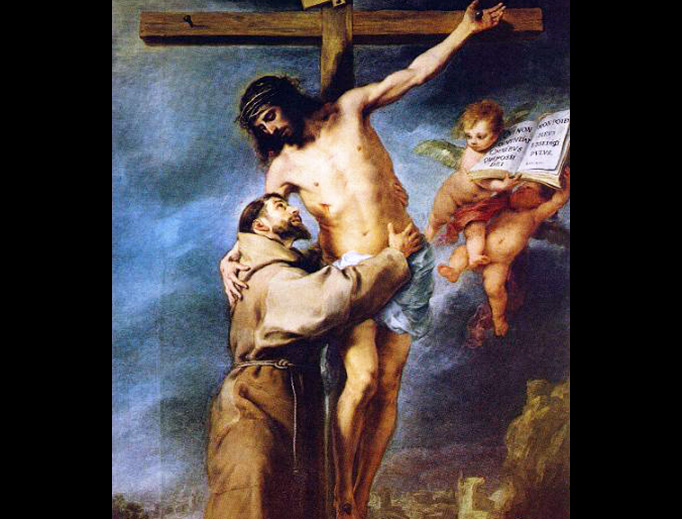

One day, a few weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, I was praying Vespers in the church by myself. A man approached me as I sat in the pew. He asked me where he could find the crucifix because he wanted to offer his pain and suffering in prayer, united to that of Jesus on the Cross. Embarrassed, I told the man that the only crucifix we had was in the church meeting room. That man, who wanted only to pray before an image of the crucified savior in a Catholic Church, looked at me with an equal amount of puzzlement and sadness and simply said, “Why do you want to hide away your cross?” Soon after that, in addition to a recumbent altar cross, we placed a crucifix in the sanctuary. My pastor purchased a beautiful Cimabue crucifix and placed it on the side of the altar.

The reaction of the parishioners to the crucifix was fascinating. The vast majority loved it. Some really hated it, considering it to be too much to look at the image of the crucified Lord. But the words of that man — “Why do you want to hide away your cross?” — was my response to those who objected to a crucifix in the sanctuary. (Fr. Longenecker’s recent article, “A Crucifix is One of the Signs of Orthodoxy”was a real joy to read.)

A question then: “Why do we want to hide away our crosses?” I don’t just mean this liturgically, because the issue is settled in the current General Instruction of the Roman Missal. I mean this in our own lives. “Why do we want to hide away our crosses?” Because I know that I do, all the time. I don’t even want to acknowledge that I have crosses. And I certainly do not want to carry them.

We have to acknowledge that we all, each in our own ways, carry a cross. Each of us has some suffering that we bear. Acknowledging my cross makes me realize that I can’t hide away my cross. I can try mightily to hide it, but I can’t escape its shadow. We all know that each of us, no matter who we are, carry a cross.

The cross makes me uncomfortable. In it, we see Jesus bloodied, broken, bruised and battered. But I really don’t want that, not in my life. I want the Resurrection, not the Passion. I don’t want to suffer. I don’t want the people whom I love to suffer.

And yet, in little ways and in grand ways, we all suffer. And suffering can cause us to doubt the goodness of God. Pain, doubt, worry and anxiety, even death can make even the strongest of believers question the mercy of God.

The great Christian writer C.S. Lewis offered a deep theology of God and human suffering in his work, The Problem of Pain. Lewis holds for the goodness of our all-powerful and all-loving God. He describes suffering as “a megaphone to rouse a deaf world,” making us recognize our dependence on our Creator. Suffering puts to death our pride and helps us grow in humility. Lewis writes:

“We must not think Pride is something God forbids because He is offended at it, or that Humility is something He demands as due to his own dignity — as if God Himself was proud.... He wants you to know Him: wants to give you Himself.”

A sign of Christian maturity is recognizing that everybody hurts — and then not fixating on it, trying to stop suffering. I can’t. You can’t. It’s part of the fallen human condition. What it means for me is to unite suffering to that of Jesus’s and see it as redemptive.

Saint Thérèse, the Little Flower and Doctor of the Church, wrote in her Story of a Soul:

“I understood that to become a saint one had to suffer much, seek out always the most perfect thing to do, and forget self. I understood, too, that there are many degrees of perfection and each soul was free to respond to the advances of the Our Lord, to do little or much for Him, in a word, to choose among the sacrifices He was asking. Then, as in the days of my childhood, I cried out: 'My God I choose all!' I do not want to be a saint by halves. I'm not afraid to suffer for You. I fear only one thing: to keep my own will; so take it, for I choose all that You will!”

Recognizing and embracing the cross that we bear — that’s the triumph of the Cross. Growth and glory come through suffering and no other way. The Cross shows us what wonderous love that Love Himself has for us. It can be no other way. “Why would you want to hide away your cross?” That’s why we say Ave Crux Spes Unica: Hail, O Cross, our only hope.