Why Chesterton Loved Christmas Carols (Especially Dickens’)

G.K. Chesterton reminds us that part of the effect of Scrooge’s Christmas visions is that “they convert us.”

Gilbert Keith and Frances Chesterton celebrated Christmas with poems and plays. Frances Chesterton wrote a poem every year for their Christmas card; one of her poems, “Here is the Little Door” was set to music by Herbert Howells and has been featured in the Nine Lessons and Carols from King’s College Chapel, Cambridge and elsewhere. Frances also wrote plays for the many godchildren and other children who celebrated with them. Nancy Carpentier Brown has collected these works in How Far Is It to Bethlehem.

Chesterton wrote many essays and poems for Christmas too. His reflections have been collected in a book of Advent and Christmas meditations, and there is an out of print collection of poems and essays which is indeed rare and expensive (The Spirit of Christmas)—and a newer edition of essays (A Chesterton Christmas: Essays, Excerpts, and Eggnog). In The Everlasting Man, the chapter titled “The God in the Cave” is Chesterton’s extended meditation on the First Christmas, the Nativity, with discussion of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Angels, the shepherds, and the Wise Men. In his prose, Chesterton describes something he also expressed in poetry (“Gloria in Profundis”):

Christ was not only born on the level of the world, but even lower than the world. The first act of the divine drama was enacted, not only on no stage set up above the sight-seer, but on a dark and curtained stage sunken out of sight; and that is an idea very difficult to express in most modes of artistic expression. It is the idea of simultaneous happenings on different levels of life. Something like it might have been attempted in the more archaic and decorative medieval art. But the more the artists learned of realism and perspective, the less they could depict at once the angels in the heavens and the shepherds on the hills, and the glory in the darkness that was under the hills. Perhaps it could have been best conveyed by the characteristic expedient of some of the medieval guilds, when they wheeled about the streets a theatre with three stages one above the other, with heaven above the earth and hell under the earth. But in the riddle of Bethlehem it was heaven that was under the earth.

But of course Chesterton loved Christmas: he loved children, he loved wonder, he loved Jesus, and he loved Christmas carols. He also loved Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

“Dickens's great defence of Christmas”

Chesterton appreciated how much Charles Dickens had done to revive the spirit of Christmas in England, bringing back—without intending it—some aspects of Catholic Merry Old England. Charles Dickens was as anti-Catholic as many of his countrymen in Victorian England and had a general dislike of organized religion, because he thought its practitioners were hypocritical. Yet, as Chesterton noted in two studies of Charles Dickens, he brought the celebration of Christmas back, emphasizing family, festivity, and charity. Chesterton says that Dickens did this in spite of his view of the Old World and Merry Old England:

“But for all that he defended the mediæval feast which was going out against the Utilitarianism which was coming in. He could only see all that was bad in mediævalism. But he fought for all that was good in it. And he was all the more really in sympathy with the old strength and simplicity because he only knew that it was good and did not know that it was old. He cared as little for mediævalism as the mediævals did.” (“Dickens and Christmas”)

Dickens just knew that the poor and the working class needed leisure and celebration as much or more than the rich did, and that in our charity we should make sure that they are able to celebrate Christmas.

The celebration of Christmas had its up and downs in England; some of its festivity had been stripped away after the English Reformation with the suppression of the Boy Bishops installed on St. Nicholas Day and rejection of other merry fun; the Puritans under Oliver Cromwell tried to ban it completely after the English Civil War in the seventeenth century—Christmas was just too Catholic for Protestants in England. They recognized the significance of the name: Christmas (Mass).

Christmas Past, Present, and Future

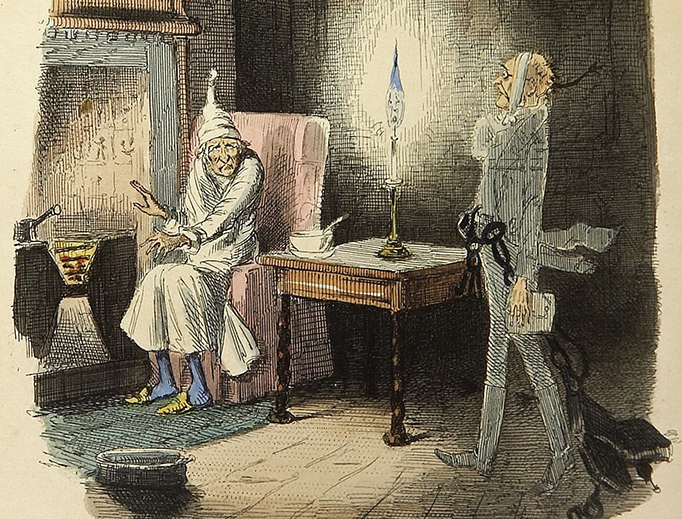

By depicting the various celebrations and moods of Christmas in Ebenezer Scrooge’s past, present, and future, Dickens presents scenes of dancing, partying, playing, feasting, and praying. His first employer showed Scrooge the balance between work and leisure, reminding him of what he’s forgotten when Fezziwig calls a halt to work on Christmas Eve and prepares for a great party. Scrooge’s employee Bob Cratchit celebrates a poor Christmas feast, but the spirit of love and appreciation in the Cratchit family makes up for the small goose, while his nephew Fred enjoys a lovely home and sumptuous feast while regretting that his Uncle Ebenezer refuses to come. And of course, the future Christmas, when the Cratchits mourn the loss of Tiny Tim, awakens Scrooge’s conscience, especially when contrasted to the lack of sadness at his death.

What Chesterton particularly lauds in Dickens’ development of Scrooge’s character is his conversion and the fact that the reader believes he can be converted, that he is not irredeemable:

Scrooge is not really inhuman at the beginning any more than he is at the end. There is a heartiness in his inhospitable sentiments that is akin to humour and therefore to humanity; he is only a crusty old bachelor, and had (I strongly suspect) given away turkeys secretly all his life. The beauty and the real blessing of the story do not lie in the mechanical plot of it, the repentance of Scrooge, probable or improbable; they lie in the great furnace of real happiness that glows through Scrooge and everything around him; that great furnace, the heart of Dickens.

Chesterton also reminds us that part of the effect of Scrooge’s Christmas visions is that “they convert us.” Scrooge isn't all bad—but we aren't all good either. We need conversion as much as Scrooge: we need to begin to apply the lessons of the Spirits of Christmas Past, Present, and Future to ourselves. We need to examine our own consciences and ask if can be said of us, as it was said of Scrooge at “The End of It”: “that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.” Thus Dickens concludes: “May that be truly said of us, and all of us!”

Chesterton agrees: “God bless us, everyone!”