The Unknown Story of St. Peter’s Golden Sphere

A prominent archeologist of the Fabric of Saint Peter sheds light on the glorious history of the globe on the top of the Vatican Basilica’s dome.

This golden sphere is a precious element of the most famous church in the world, especially since deep cleaning work restored its former light and luster in 2003.

When seen from below, it seems so small that it is hardly conceivable that for centuries, the sphere has been a must-see stop for crowned heads from around the world. Indeed, very few people know it is possible to access the interior of the globe, which is big enough to welcome up to 16 people.

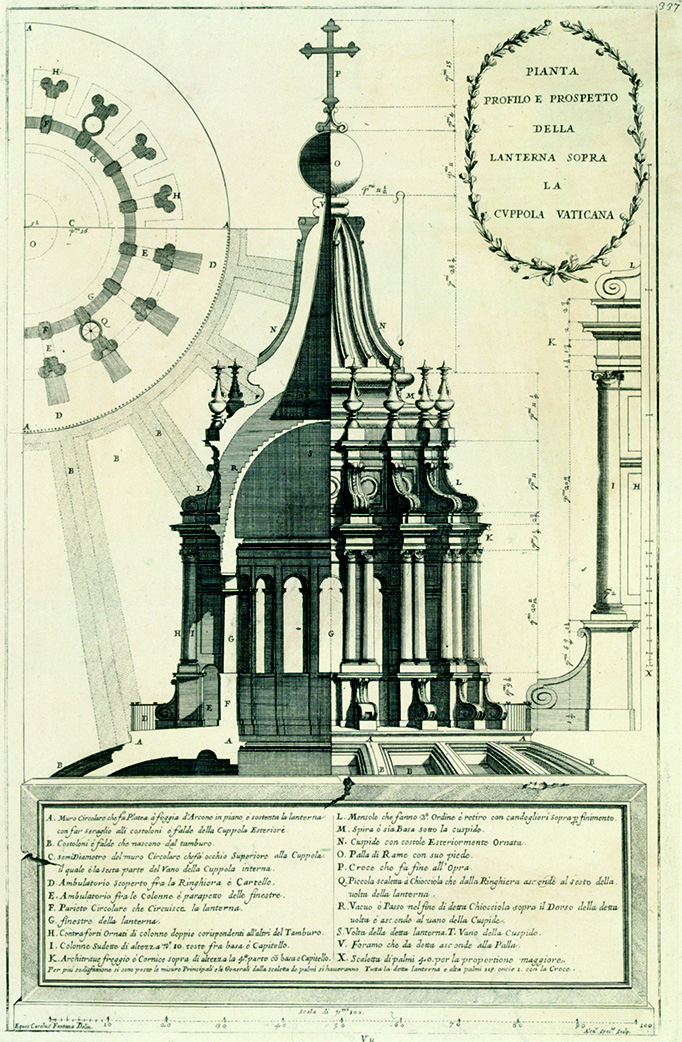

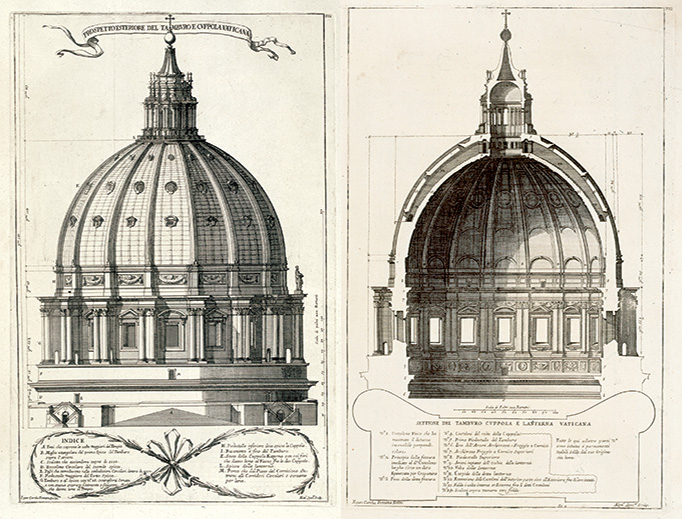

Completed July 20, 1593, the sphere was the final step, the crowning touch of the dome originally designed by Michelangelo and then slightly modified by architects Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana. According to the Office of Conservation and Restoration of the Fabric of Saint Peter, the sphere — made of 54 trapezoidal-shape pieces of mercury-gilded bronze — rises to a height of about 410 feet from the floor of the basilica and measure more than 8 feet in diameter for a total weight of 4,104 pounds. It is accessible from the top of the dome thanks to a small ladder.

“Many 19th-century guides already highlighted the magnificence of this bronze globe, but its history is very little-known today” Pietro Zander, Director of the Office of Conservation and Restoration of the Fabric of Saint Peter, told the Register. “It was a highly coveted place in the 18th century, and the most prestigious travelers shared the desire to access the dome, especially the palla.”

The latter is reportedly the last sovereign to have entered the sphere, together with Pope Gregory XVI in the mid-19th century. Indeed, the access to the inside of the globe was definitively forbidden to the public a few years later for safety and conservation reasons. Since that time, only the staff in charge of maintaining the basilica has been allowed inside.

Such measures were taken after several incidents with visitors at the narrow entrance, which is less than 3 feet wide. In his illustrated book Saint-Pierre de Rome, 19th-century French writer Charles de Lorbac mentions a story about an overweight German visitor who got stuck in the entrance of the globe. A very plausible story, according to Zander, who reminds that this kind of stories is not isolated: “Many old ‘Sanpietrini’ [the workers who are responsible for the maintaining of the basilica] that used to work here remember several episodes of corpulent people who were not able to get inside because the passage was too narrow; clearly, an obese person cannot go through the door,” he said.

And the same problem arose with the various queens who climbed the stairs to the globe, as the clothes they wore in the past centuries restricted their movement. “There are several testimonies that mention royal banquets on the terrace of the dome, during which the queens changed to continue climbing the narrow stairs and enter the sphere,” Zander added.

The last pope to have visited it is said to be Pius IX in the mid-19th century. In fact, there is no mention in the Vatican archives of a papal visit to the sphere of St. Peter since then.

The mystery surrounding this place after it became forbidden to the public gave rise to various rumors about its origin, notably the fact that the sphere was designed to welcome a table for 12 people, as a tribute to the Apostles at the Last Supper. However, although inspiring, this theory seems unfounded. “I’ve never heard about any table inside the sphere; there are only four small seats, and little windows to air the inside and let people admire the very unique and beautiful view,” Zander said, highlighting the preeminence of the symbolic dimension of the sphere. “Just like Brunelleschi’s dome on the top of the cathedral of Florence, the globe surmounted by a cross evokes the presence of the Cross among us above all; it symbolizes Christian Rome and the whole of Christendom.”

- Keywords:

- st. peter's basilica